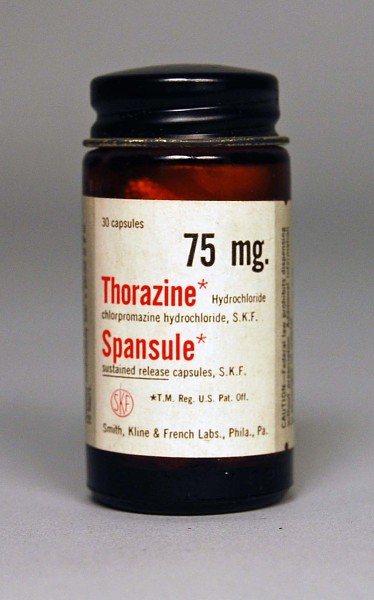

A Quick History

The very first modern psych med, chlorpromazine (Thorazine), showed up in the 1950s. Its story starts earlier, in a chemistry lab, not a psychiatrist’s office. French researchers were tinkering with compounds originally related to treatments for allergies and malaria, and one of those tweaks accidentally produced a drug that calmed patients without knocking them out cold1. At first, doctors noticed it worked well as a pre-surgical sedative, but then it became clear that this “side effect” could quiet psychosis too. Thorazine revolutionized treatment, emptied out some asylums, and set the stage for a reality patients still face today: some psychiatric medications can make the number on the scale creep up2.

Medication Categories & Weight Effects

Antipsychotics

Olanzapine and clozapine are the most likely to cause significant early weight gain, often more than ten pounds in a few months3. Risperidone and quetiapine tend to add weight more slowly, while aripiprazole, lurasidone, ziprasidone, and cariprazine are generally much lighter in this regard4. Most of the gain shows up within the first 6–12 weeks. Weight can sometimes be reduced or stabilized by switching medications, combining treatment with nutrition and exercise changes, or using add-on medications like metformin or GLP-1 agonists5.

Antidepressants

SSRIs such as sertraline, fluoxetine, and escitalopram are usually weight-neutral at first but may lead to gradual gains of 5–15 pounds over longer-term use, with paroxetine more likely to do so6. SNRIs like venlafaxine and duloxetine carry a smaller average risk. Mirtazapine often causes rapid early gain, while bupropion is usually neutral or even slightly weight-reducing. Older antidepressants such as TCAs and MAOIs are more likely to add weight7.

Mood Stabilizers

Valproate (Depakote) frequently leads to weight gain, sometimes quickly, while lithium causes mild-to-moderate changes that vary from person to person. Carbamazepine carries a lower risk, and lamotrigine is typically weight-neutral8.

Benzodiazepines

Drugs like Xanax, Klonopin, and Ativan are largely weight neutral. Indirect changes may happen if sedation lowers activity levels or encourages more snacking, but the drugs themselves don’t alter metabolism9.

Stimulants & ADHD Medications

Stimulants such as amphetamines and methylphenidate often reduce appetite and cause weight loss, especially at the start. Atomoxetine (Strattera) is usually neutral or slightly weight-lowering. Some regain can occur later in the day when appetite rebounds after the medication wears off10.

The Bigger Picture

Weight changes on psychiatric medications are not guaranteed, and when they occur, the amount and speed vary widely. Most increases happen in the first weeks to months, then level off rather than continuing endlessly. If a medication is stopped, some of the weight gain is often reversible, but not always, since the body sometimes resists moving back down.

Healthy eating, regular activity, and good sleep can reduce the risk of weight gain and help manage it if it happens. For people already concerned about weight, there are medications that tend to be safer choices, and your provider will usually weigh the mental health benefits against the physical side effects before prescribing. Sometimes a medicine with higher weight risk is still chosen because it works best for the specific symptoms at hand, and the risks can be managed.

Added pounds can carry health consequences such as higher risk for diabetes or heart disease, which is why doctors often check blood sugar and cholesterol during treatment. But it’s also important to remember that not all weight gain is dangerous, and the improvements in mood, sleep, or thought patterns can themselves reduce other health risks.

Some people wonder whether they’ll be on medication forever. In reality, treatment plans are revisited regularly, and medication can be adjusted or discontinued depending on progress and needs. Long-term use doesn’t automatically mean long-term weight gain. There are also safe options to help manage the side effects, from switching medications to adding targeted treatments that reduce appetite or improve metabolism.

Ultimately, psychiatric medications can be life-changing and even lifesaving. Side effects like weight changes are important but manageable, and they never mean that someone has failed. The real goal is finding a treatment that restores stability and well-being while minimizing burdens — a balance that looks a little different for every individual.

Other Common Side Effects People Worry About

While weight changes grab a lot of attention, they’re far from the only side effects patients bring up. Some of the most common concerns include:

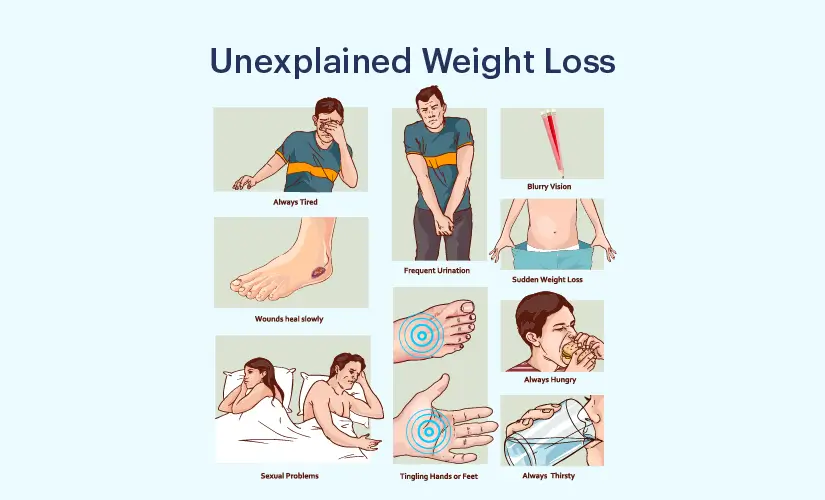

- Sedation or Fatigue: Many psychiatric medications can make people feel drowsy, especially antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, and some antidepressants11.

- Sexual Side Effects: SSRIs, SNRIs, and some antipsychotics can reduce libido, delay orgasm, or cause erectile difficulties12.

- Digestive Issues: Nausea, constipation, or diarrhea can show up, particularly with antidepressants and stimulants13.

- Sleep Disturbances: Some medications (like bupropion or stimulants) may cause insomnia, while others (like quetiapine or mirtazapine) can make sleepiness overwhelming14.

- Movement or Muscle Effects: Antipsychotics in particular can cause restlessness (akathisia), tremors, or muscle stiffness, though newer ones tend to have a lower risk15.

- Dry Mouth, Blurred Vision, or Dizziness: Often linked to older antidepressants or medications with strong anticholinergic effects16.

Sleep Meds: What Are People Using (and Are They Safe?)

There are a lot of ways to nudge sleep, which is wild considering almost everyone needs it and yet no single option is a slam dunk for everyone.

- The Z-drugs (Ambien, Lunesta, Sonata): Work on similar receptors as benzos, can help with falling asleep and sometimes staying asleep, but are linked to next-day sedation and odd “sleep behaviors”17. This is called “anterograde amnesia”, meaning everything that you think after taking this pill you will not remember. This leads to dangerous driving, cooking and eating, and today it can involve strange middle-of-the-night tweets you will likely regret.

- Orexin blockers (Belsomra, Dayvigo, Quviviq): Shut down the brain’s “wake drive.” Many patients like them for being less groggy the next morning, though they’re expensive and insurance coverage varies17.

- Melatonin receptor agonist (Rozerem): Modest effect, no abuse risk — useful for circadian rhythm issues more than insomnia itself17.

- Tricyclic antidepressant in low dose (Silenor): Helps sleep maintenance without the baggage of higher antidepressant doses17.

- Benzodiazepines (Restoril, Halcion): Effective, but dependence, tolerance, and fall risk limit their role17.

- Antihistamines (Vistaril, Benadryl): Common, cheap, and widely marketed, but tolerance develops fast and next-day grogginess is common17.

- Gabapentin: Sometimes helps if pain or restless legs are involved, but not FDA-approved for sleep17.

- Trazodone and Seroquel: Sleepiness is a side effect, not their true purpose, which is ironic given how often they’re prescribed for exactly that17.

- Clonidine (Catapress): Off-label for sleep, sometimes used in kids or when stimulants disrupt nighttime settling17. These do not interfere with your sensorium. Also used for some forms of ADHD.

Supplements for Sleep: The Hype vs. The Science

Walk into any natural grocer and the shelves scream: Melatonin! Magnesium! Valerian! CBD! They are marketed like magic bullets, but the reality is less glamorous.

- Melatonin: It is not actually a “sleeping pill.” It works by shifting the body’s circadian rhythm, signaling that it is time for sleep. Peak effectiveness is at low doses (0.5–3 mg), yet it’s often sold in 5–10 mg tablets that overshoot what the body makes naturally18. Taking it right before bed also makes little sense — melatonin needs to be timed about an hour or two before bedtime to help set the body clock19. High doses may backfire, leading to grogginess the next day.

- Magnesium: May help if someone is deficient or has restless legs. Effects are modest, but supplements are inexpensive (~$10–20/month)20.

- Valerian root, chamomile, L-theanine: Evidence is mixed to weak. Some people find them calming, others see no change20.

- CBD and cannabis products: Widely marketed, expensive, and still lacking solid clinical trial evidence20.

Marketing problem: These supplements are sold as though they are equivalent to prescription sleep aids. In the U.S., the supplement industry is lightly regulated, meaning potency, purity, and labeling can vary widely21. Insurance doesn’t cover them, so the costs fall entirely on patients.

Who Uses Sleep Aids?

In 2020, about 8.4% of U.S. adults used sleep medications regularly in the prior month22. Use varies by demographic group:

- Gender: Women (10.2%) were more likely than men (6.6%) to use sleep medications regularly22.

- Age: Use rises significantly with age.

- Race/Ethnicity: Non-Hispanic White adults report more sleep medication use than other racial or ethnic groups22.

Among teens, insomnia is reported more by girls than boys23.

Sleep and Weight: The Connection

Here’s where it all circles back. Sleep isn’t just about being rested — it directly affects weight. There is no substitute!

- Poor sleep = more weight gain. Sleep deprivation lowers leptin (the “full” hormone) and raises ghrelin (the “hungry” hormone), driving late-night snacking24.

- Sedating meds like Seroquel, trazodone, or antihistamines can increase appetite and slow metabolism, compounding the risk24.

- Melatonin itself doesn’t cause weight gain, but better sleep may reduce stress-eating and improve glucose control25.

- Supplements like magnesium might modestly help metabolic health, but evidence is mixed25.

So, whether you go with a prescription, an over-the-counter supplement, or both, the ripple effects on weight are part of the bigger picture.

References (Final Combined List):

- Loonen, A. J. M., & Ivanova, S. A. (2013). New insights into the mechanism of drug action of antipsychotics: Importance of the muscarinic system. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 23(1), 82–91. ↩

- Healy, D. (2002). The creation of psychopharmacology. Harvard University Press. ↩

- Allison, D. B., Mentore, J. L., Heo, M., Chandler, L. P., Cappelleri, J. C., Infante, M. C., & Weiden, P. J. (1999). Antipsychotic-induced weight gain: A comprehensive research synthesis. American Journal of Psychiatry, 156(11), 1686–1696. ↩

- Lieberman, J. A., Stroup, T. S., McEvoy, J. P., et al. (2005). Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. New England Journal of Medicine, 353(12), 1209–1223. ↩

- Baptista, T., Serrano, A., Uzcátegui, E., El Fakih, Y., Rangel, N., Carrizo, E., & de Baptista, E. A. (2008). Metformin for prevention of weight gain with antipsychotics: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 22(5), 532–538. ↩

- Serretti, A., & Mandelli, L. (2010). Antidepressants and body weight: A review and meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 71(10), 1259–1272. ↩

- Fava, M. (2000). Weight gain and antidepressants. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 61(Suppl 11), 37–41. ↩

- Biton, V. (2003). Weight change and anticonvulsants: Valproate and lamotrigine. Epilepsy Research, 56(3), 185–193. ↩

- Shader, R. I., & Greenblatt, D. J. (1993). Benzodiazepines revisited. New England Journal of Medicine, 328(19), 1398–1405. ↩

- Faraone, S. V., Biederman, J., Morley, C. P., & Spencer, T. J. (2008). Effect of stimulants on growth in children with ADHD: A meta-analysis. Pediatrics, 122(1), e1–e14. ↩

- Sateia, M. J., Buysse, D. J., Krystal, A. D., Neubauer, D. N., & Heald, J. L. (2017). Clinical practice guideline for the pharmacologic treatment of chronic insomnia in adults. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 13(2), 307–349. ↩

- de Crescenzo, F., et al. (2022). Comparative effects of pharmacological interventions for insomnia disorder in adults: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. The Lancet, 400(10349), 170–184. ↩

- Adjaye-Gbewonyo, D., Ng, A. E., & Black, L. I. (2022). Sleep difficulties in adults: United States, 2020. NCHS Data Brief No. 436. Hyattsville, MD: CDC. ↩

- Reuben, C., Elgaddal, N., & Black, L. I. (2023). Sleep medication use in adults aged 18 and over: United States, 2020. NCHS Data Brief No. 462. Hyattsville, MD: CDC. ↩

- Matheson, E., & Hainer, B. L. (2017). Insomnia: Pharmacologic therapy. American Family Physician, 96(1), 29–35. ↩

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2016–2022). Labels for Ambien, Lunesta, Sonata, Rozerem, Belsomra, Dayvigo, Quviviq, Silenor, Restoril, Vistaril, Kapvay. FDA. ↩

- Sateia, M. J., & Buysse, D. J. (2017). Insomnia treatments and their risks. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 13(2), 307–349. ↩

- Ferracioli-Oda, E., Qawasmi, A., & Bloch, M. H. (2013). Meta-analysis: Melatonin for the treatment of primary sleep disorders. PLoS One, 8(5), e63773. ↩

- Zhdanova, I. V. (2005). Melatonin as a hypnotic: Pro. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 9(1), 51–65. ↩

- Bent, S., et al. (2006). Valerian for sleep: A systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Medicine, 119(12), 1005–1012. ↩

- Cohen, P. A. (2014). Hazards of poorly regulated dietary supplements. JAMA Internal Medicine, 174(10), 1727–1734. ↩

- Reuben, C., Elgaddal, N., & Black, L. I. (2023). Sleep medication use in adults aged 18 and over: United States, 2020. NCHS Data Brief No. 462. ↩

- Hysing, M., et al. (2013). Sleep patterns and insomnia among adolescents: A population-based study. Journal of Sleep Research, 22(5), 549–556. ↩

- Spiegel, K., Tasali, E., Penev, P., & Van Cauter, E. (2004). Sleep curtailment in healthy young men is associated with decreased leptin, elevated ghrelin, and increased hunger. Annals of Internal Medicine, 141(11), 846–850. ↩

- Veronese, N., et al. (2017). Effect of magnesium supplementation on glucose metabolism in people with or at risk of diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 70(12), 1354–1359. ↩