During my psychiatry residency and fellowship, we met weekly to watch a film and then gather in a room to dissect it. These were not casual Netflix nights with snacks and a side of gossip. They were deep dives into character motivation, symptom portrayal, ethical dilemmas, and cultural subtext. We would watch a scene, stop it, argue about diagnostic accuracy, debate treatment approaches, and sometimes just marvel at how a particular performance captured the essence of a condition. This ritual of gathering with colleagues, sharing perspectives, and finding truth in art was one of the reasons I chose psychiatry as my field. There is no shortage of subject matter. Humanity gives us all the material we could ever need.

And perhaps nowhere is that more vivid than in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975). Miloš Forman’s adaptation of Ken Kesey’s novel is both a rebellion story and a psychiatric time capsule. Jack Nicholson’s Randle McMurphy is a swaggering small-time criminal who thinks pretending to be insane will get him a cushy ride. Instead, he finds himself under the unblinking gaze of Louise Fletcher’s Nurse Ratched, a woman who can cut you down without raising her voice. The ward hums with electric tension: group therapy sessions that feel like ambushes, medication lines that feel like surrender, and the slow erosion of individuality in the name of “care.” At the 1976 Academy Awards, it swept the “Big Five”: Best Picture, Best Director for Forman, Best Actor for Nicholson, Best Actress for Fletcher, and Best Adapted Screenplay for Lawrence Hauben and Bo Goldman. Only two other films have ever done that. This one is the only to do it while taking a scalpel to institutional psychiatry and showing the scars.

Flash-cut to Gotham City in Joker (2019), where Todd Phillips — formerly of The Hangover fame — trades beer bongs for bleakness. Joaquin Phoenix’s Arthur Fleck is a man already teetering, making a living as a party clown while caring for his ailing mother. The city is filthy, the people cruel, the social services funding cut. Arthur’s world is shrinking and tilting, and we watch as his reality fractures into the persona that will become the Joker. The camera doesn’t flinch, and neither does Phoenix, whose Best Actor Oscar was as much for the physical transformation as for the unnerving vulnerability he brings to a man everyone has decided to ignore. Hildur Guðnadóttir’s haunting score won an Oscar too, winding itself around Arthur’s descent like a slow-tightening noose. On television, Mr. Robot offers a long-form counterpart: Rami Malek’s Elliot Alderson, a brilliant hacker whose paranoia and dissociation leave you unsure what’s real — and you don’t care because it’s so hypnotically performed. Malek won the Emmy for it, and you will believe he earned it.

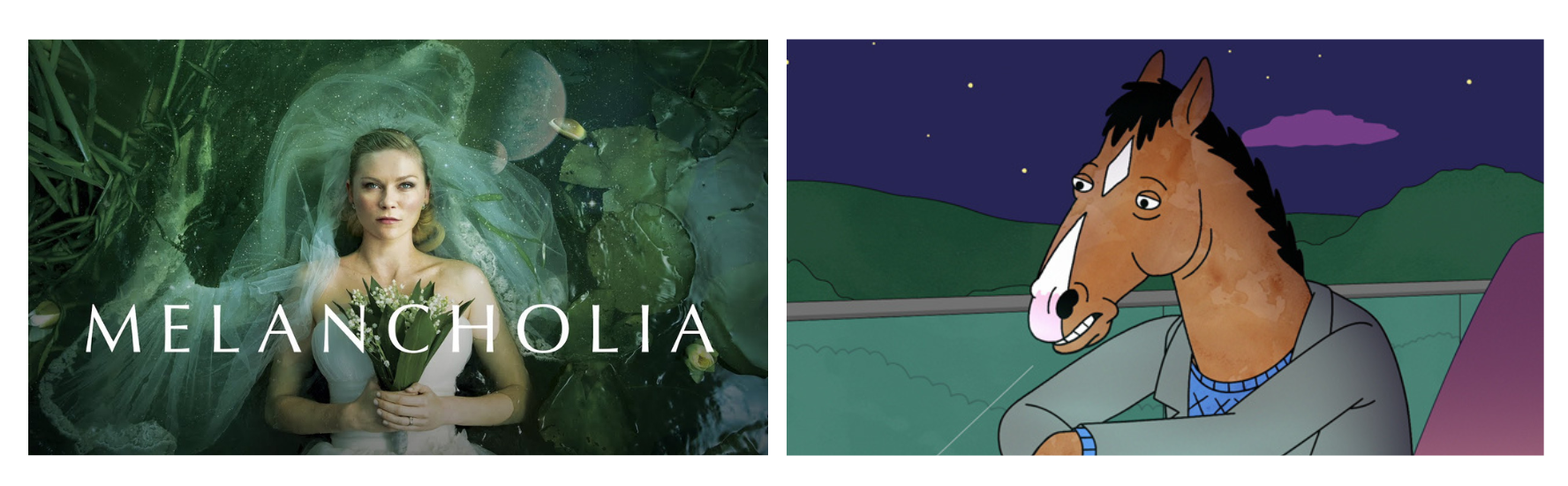

Depression reaches operatic beauty in Melancholia (2011). Lars von Trier opens with a slow-motion dream sequence of a planet on a collision course with Earth, scored to Wagner. Kirsten Dunst’s Justine drifts through her own wedding like a ghost, watching as joy slides off her like water off marble. The film is divided into two halves: one focused on her collapse, the other on her sister’s desperate attempts to keep life moving as the end of the world approaches. It’s as if depression itself is a celestial body, pulling everything toward it. Dunst won Best Actress at Cannes for embodying a kind of despair that is beautiful only because it’s honest. Bojack Horseman on Netflix takes that same unflinching gaze to depression, stretching it over six seasons. Yes, he’s a cartoon horse. Yes, he drinks too much, sabotages relationships, and talks in deadpan sarcasm. And yes, at some point, you will realize you’ve stopped laughing and started recognizing yourself.

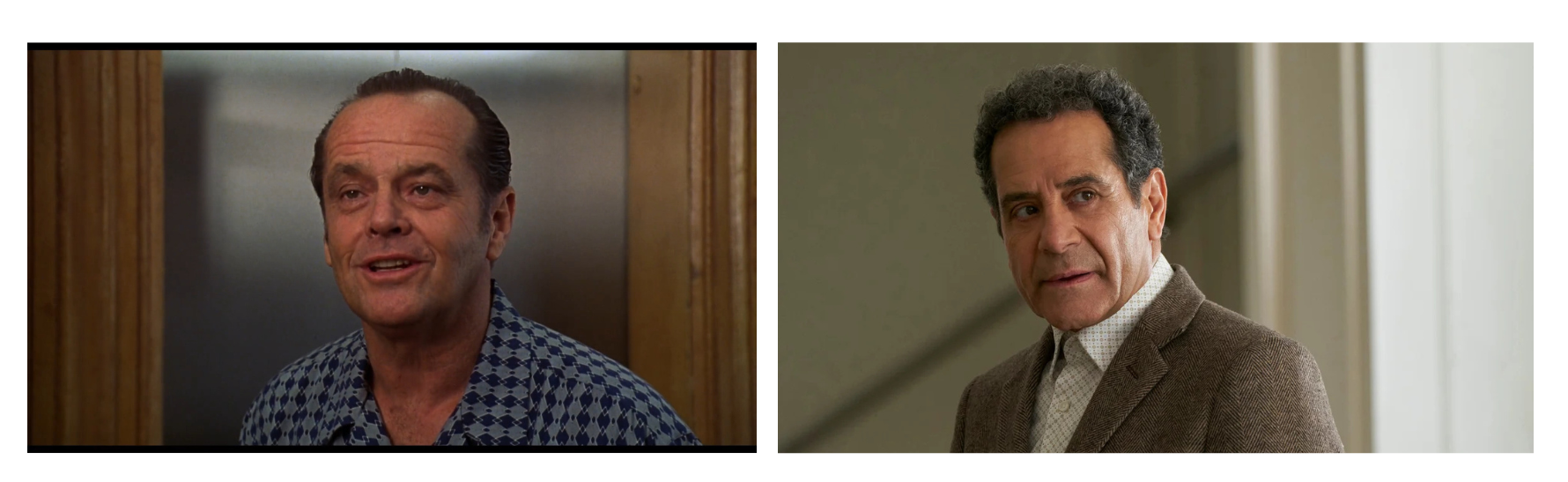

If anxiety had a movie star, it would be Jack Nicholson in As Good as It Gets (1997). As Melvin Udall, he plays a romance novelist whose obsessive-compulsive disorder makes crossing the street a mental minefield. He avoids cracks in the sidewalk like they might swallow him whole, eats at the same table in the same restaurant, and brings his own plastic utensils like a man at war with germs. Nicholson won his third Oscar for the role, Helen Hunt won hers for playing the woman who chips away at his armor, and the film itself remains one of the rare romantic comedies that takes mental illness seriously while still letting you enjoy the ride. Television’s Monk turns OCD into a detective’s edge: Tony Shalhoub’s Adrian Monk solves cases no one else can because he notices what no one else does, even if it means washing his hands fifty times a day. Shalhoub’s three Emmys for the role are as deserved as his character’s constant supply of disinfectant wipes.

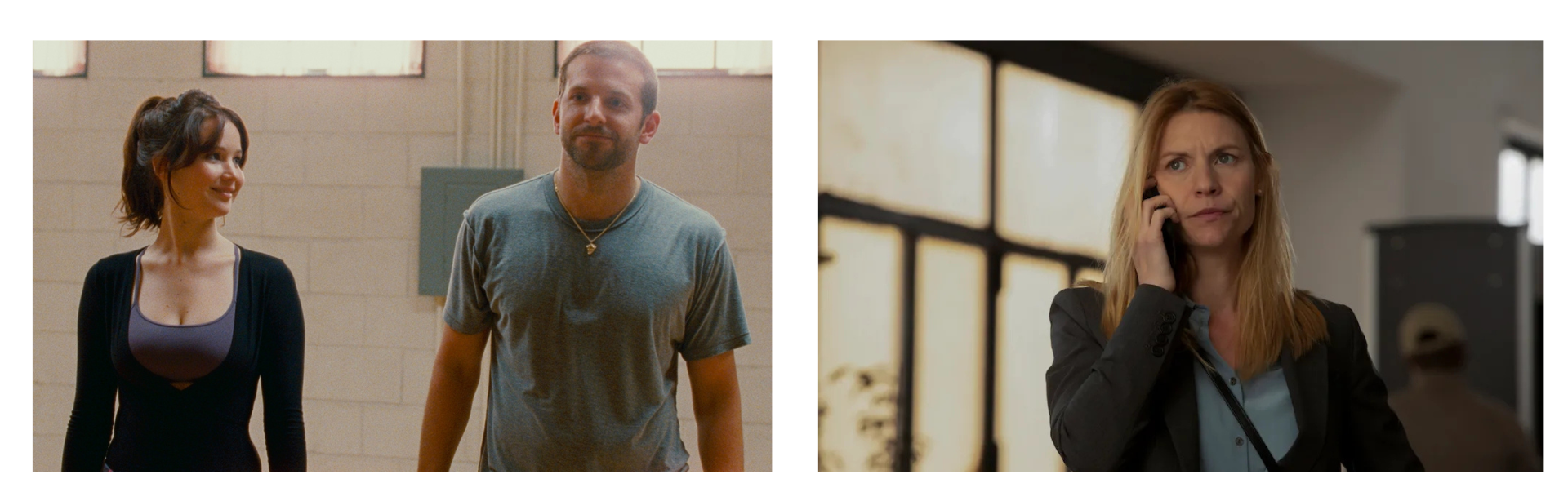

Bipolar disorder twirls into Silver Linings Playbook (2012), a movie that is equal parts love story, sports movie, and mood-swing showcase. Bradley Cooper’s Pat is fresh from a psychiatric hospital, determined to win back his ex-wife, working out compulsively, and prone to conversational grenades that clear entire rooms. Enter Jennifer Lawrence’s Tiffany, equally damaged in her own way, who lures him into a ballroom dance competition. It’s loud, messy, and tender. Lawrence won Best Actress, and the film pulled off the rare feat of earning Oscar nominations in all four acting categories. Homeland takes bipolar disorder out of the dance hall and into the war room, with Claire Danes’ Carrie Mathison chasing terrorists while her own manic and depressive episodes become both her superpower and her undoing. Two Emmys and two Golden Globes later, it’s still one of television’s most riveting portrayals of the condition.

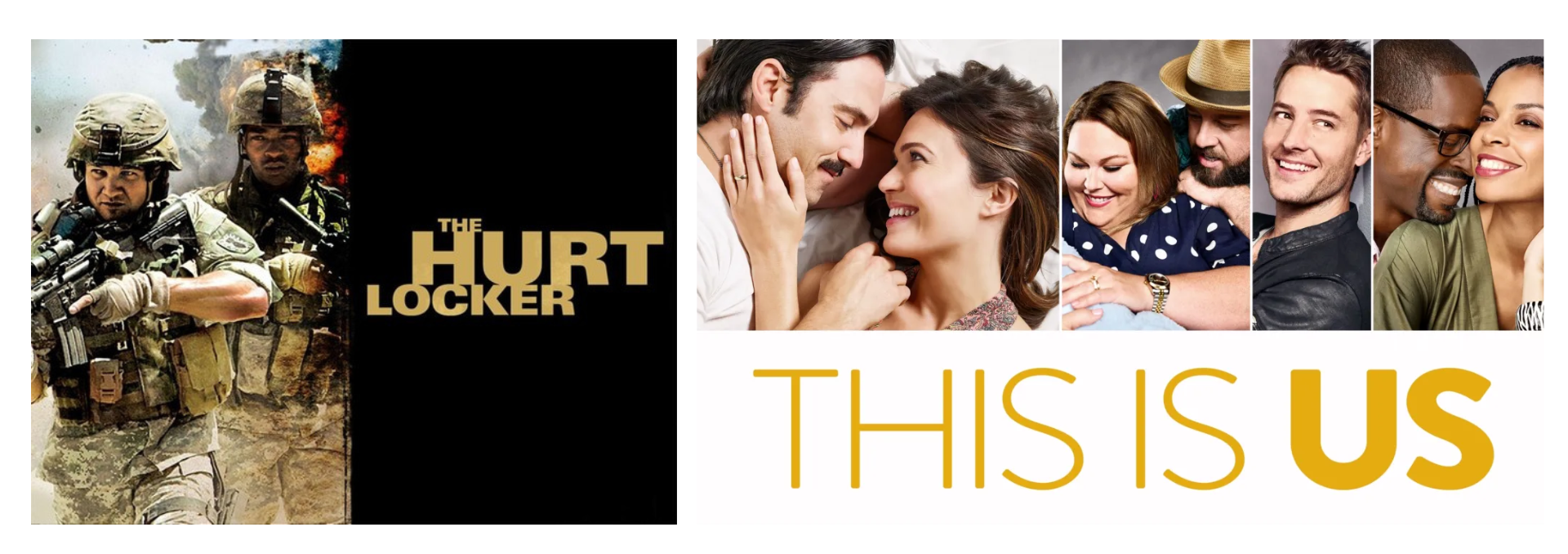

PTSD ticks like a time bomb in The Hurt Locker (2008). Jeremy Renner plays a bomb disposal expert in Iraq whose adrenaline addiction is so strong that civilian life feels alien. Who can forget Jeremy Renner’s performance after returning from a tour of duty, standing overwhelmed in the cereal isle of a supermarket. Kathryn Bigelow directs with such precision that you feel your own pulse spike as the countdowns tick. Bigelow made history as the first woman to win the Oscar for Best Director, and the film won Best Picture along with four other Academy Awards. In This Is Us, PTSD is quieter but just as insistent: Kevin’s panic attacks, triggered by grief and loss, ripple out through the family drama. It is television’s gentler way of saying that the battlefield is not always overseas.

Abuse scorches Precious (2009) from the inside out. Gabourey Sidibe’s Precious is an illiterate Harlem teenager pregnant for the second time by her father, battered physically and emotionally by her mother, and utterly without a safety net. It is a portrait of cruelty, but also of the stubborn will to survive. Mo’Nique’s Oscar-winning turn as the abusive mother is almost unbearable to watch in its honesty. Maid on Netflix captures the other side of abuse — the escape. Margaret Qualley’s Alex scrubs houses while navigating poverty, gaslighting, and a legal system that seems almost designed to push her back into harm’s way. It’s quieter, but no less devastating.

Captivity becomes a warped form of reality in Room (2015). Brie Larson’s Ma has been held prisoner for years in a tiny garden shed, raising her son in a world of four walls. When they escape, the world outside is as overwhelming as the captivity was suffocating. Larson’s performance won her the Best Actress Oscar, and Jacob Tremblay’s heartbreaking turn at age nine should have earned him one too. Unbelievable on Netflix is not about physical captivity, but about the emotional one that follows when a sexual assault survivor is called a liar by the very people meant to protect her. It won a Peabody Award for telling that story with restraint and fury in equal measure. This is particularly potent now, considering how abuse victims counter today’s politics regarding Jeffrey Epstein and Ghislaine Maxwell.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder traps genius in The Aviator (2004). Leonardo DiCaprio’s Howard Hughes builds planes, breaks records, and slowly retreats into rituals that control his life: repeating phrases until they “feel right,” refusing to touch anything unsterilized, isolating himself from the world he once dominated. Cate Blanchett won Best Supporting Actress for her dazzling Katharine Hepburn, but it’s DiCaprio’s portrayal of OCD’s slow, suffocating creep that lingers. On television, Pure finally shows intrusive sexual thoughts for what they are: distressing, unwanted, and exhausting, rather than turning them into a cheap joke.

Paranoid psychosis gets the Oscar-winning biography treatment in A Beautiful Mind (2001). Russell Crowe’s John Nash is a math prodigy whose mind is also generating people who do not exist and conspiracies that are not real. Jennifer Connelly won Best Supporting Actress as his wife, holding onto him even when reality does not. The film won Best Picture, Best Director for Ron Howard, and Best Adapted Screenplay, making it a prestige machine. The Outsider on HBO merges psychosis with supernatural horror until you cannot tell where one ends and the other begins.

Neurodevelopmental disorders get their mainstream debut in Rain Man (1988). Dustin Hoffman’s Raymond is an autistic savant whose routine-driven life is upended when his estranged brother, played by Tom Cruise, discovers him. The road trip that follows is part manipulation, part bonding, and entirely absorbing. Hoffman won Best Actor, and the film won Best Picture, Best Director for Barry Levinson, and Best Original Screenplay. Atypical on Netflix offers a more modern portrayal of autism through Sam, a teenager navigating school, dating, and independence, with warmth and humor.

And so on through trauma in The Perks of Being a Wallflower, dissociation in United States of Tara, eating disorders in Black Swan and My Mad Fat Diary, gender dysphoria in Boys Don’t Cry and Pose, addiction in Requiem for a Dream and Euphoria, personality disorders in Girl, Interrupted and Killing Eve, paraphilias in The Woodsman and SVU, and grief in Manchester by the Sea and After Life. Each one a case study wrapped in story, art, and sometimes a statue or two.

These films and shows do not just dramatize mental illness. They hold up a mirror to the ways we live, cope, hurt, and heal. They sparked debates in my residency screening room, pushed me toward a field where stories and symptoms are always entwined, and proved there is no shortage of subject matter when you work in psychiatry. If you want to talk more about these portrayals, compare notes, or even share your own favorites, you can reach me at my website Boulder Psychiatry Associates.