Psychiatry has changed a lot in the past ten years, and not just because therapists have started using words like “vibes” in their intake notes. It’s not just about diagnosing depression anymore. These days, psychiatry is dealing with everything from gender identity to parenting styles to whether your kid’s tantrum means he needs therapy or just a nap. It’s confusing, it’s political, and depending on who you ask, it’s either progress or the total collapse of civilization. So, let’s take a walk through the weird, wild world of modern mental health and see how we got here.

First off, psychiatry used to treat women and LGBTQ+ folks like some kind of mysterious psychological side quest. For most of history, if you were a woman and you were mad, sad, or just didn’t feel like smiling on demand, there was a good chance someone would call it hysteria and try to sedate you. If you were gay or trans, they might try to fix you with shock therapy or “praying away the gay” with a kind of sadistic aversion therapy. But in the past decade or so, there’s been a major shift. Instead of trying to make people “normal,” psychiatry has started listening to what people actually say about their own identities. Now there’s more attention on how mental health plays out differently for different kinds of people, and that’s led to better treatment, or at least less insulting treatment. And yes, a lot of this change has also made its way into the culture at large, which means everyone has opinions about it, whether they’re a mental health expert or just a guy yelling on Facebook. In fact, since 2015, the number of LGBTQ+ individuals reporting access to affirming mental health care has increased by 38%1, which sounds great until you realize that still only gets us to about half of those who need it.

Then we’ve got the topic of kids and behavior, which is basically a modern horror film for some parents. Here’s the setup: you’ve got a kid who can’t sit still in class, argues all the time, zones out during chores, and climbs the walls at home. Is this kid evil? Or just bored? Or is it ADHD? Maybe it’s anxiety. Maybe he needs a therapist. Or a pill. Or a different school. Or maybe the adults around him need to calm down and get off YouTube for five minutes. Parenting has changed a lot too. Back in the day, if a kid acted out, the parent might yell or ground them or just ignore it. Now, it’s much more likely someone’s booking a consult to find out if that kid needs a diagnosis and a prescription. According to the CDC, 1 in 5 kids in the U.S. now has a diagnosed mental, emotional, or behavioral disorder2, and nearly 13% of kids ages 3 to 17 are on some form of psychiatric medication3. Some of that’s great because we do have meds that help people focus and feel better. But some of it feels like trying to solve emotional problems with a chemical restraint. It’s like we’re asking: is this kid really struggling or are we just uncomfortable with what being a kid looks like these days?

And that brings us to the very complicated issue of what we even mean when we say “bad behavior.” Once upon a time, bad behavior was simple. It was coloring on the walls, talking back, skipping homework, maybe launching your grilled cheese across the cafeteria like a discus. It meant you were being a brat, and you got punished, the end. But now? Now “bad behavior” could mean you’re having a trauma response. Or your brain is wired differently. Or your nervous system is on fire because someone made you sit in a fluorescent-lit classroom for seven hours straight without snacks. We’ve gone from “You’re grounded” to “Let’s schedule a neuropsych eval.” Parents are now detectives, trying to figure out if their kid’s refusal to brush their teeth is oppositional defiant disorder, sensory processing disorder, anxiety, iron deficiency, gluten intolerance, or the early signs of giftedness. Seriously, the same behavior can now be labeled as a cry for help, a chemical imbalance, or just being five. And that makes sense, in a way, because sometimes behavior is communication, not rebellion. But it also means we’ve built this weird system where normal kid stuff gets medicalized, because god forbid a child be weird or loud or have a personality during business hours. Just to put numbers on it: 6.1 million kids in the U.S. have been diagnosed with ADHD4, over 7 million have anxiety5, and more than half of them aren’t even receiving consistent therapy. And let’s not forget that U.S. schools have increased behavior-related suspensions by over 20% since 20106, even as diagnoses have gone up, not down.

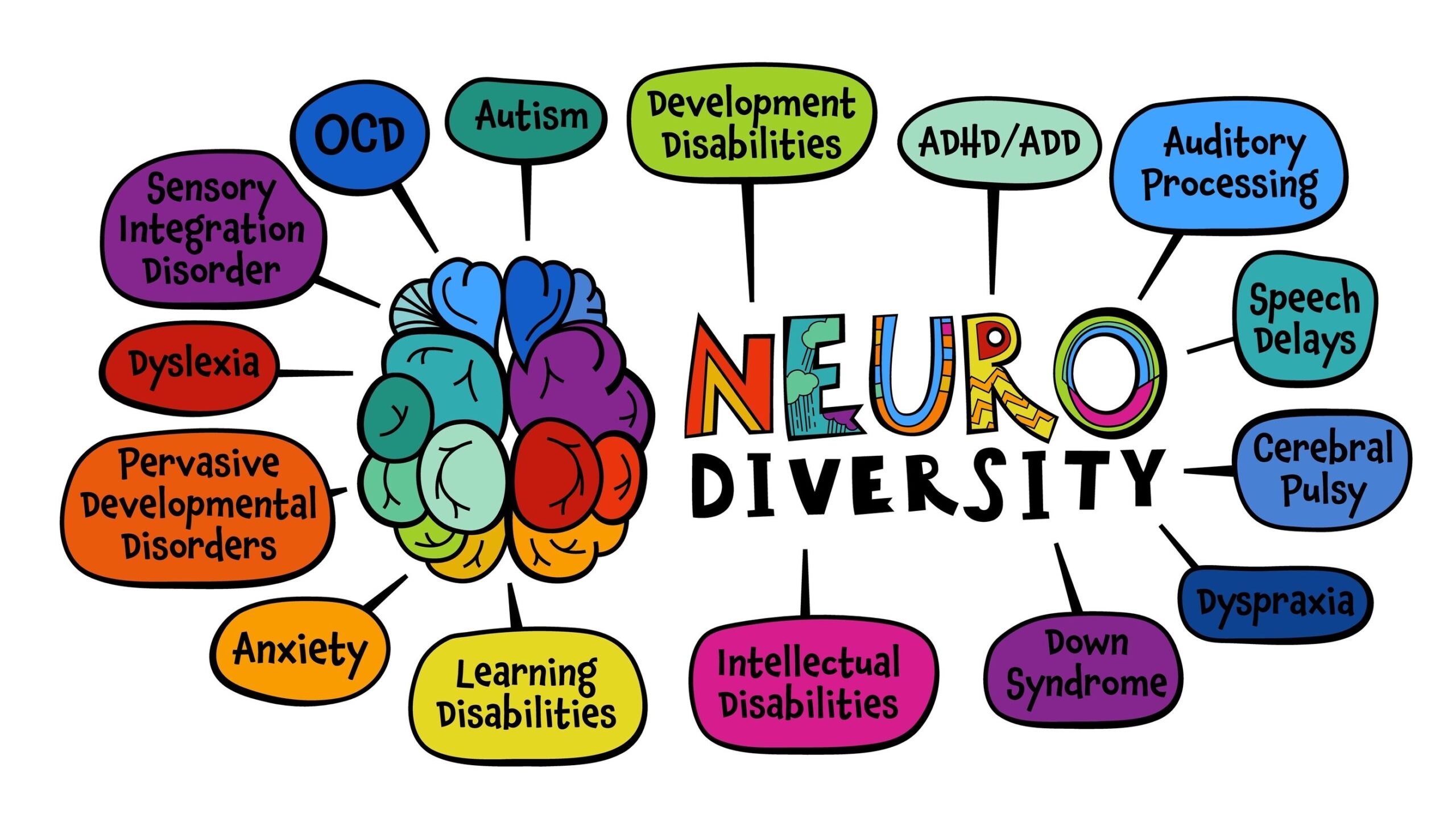

All of this ties into the rise of something called “neurodivergence,” which sounds like a futuristic Marvel superpower but is really just a new way of looking at old problems. Instead of saying someone “has a disorder,” the neurodiversity movement says maybe their brain just works differently. ADHD, autism, dyslexia, even some mood issues are now seen by a lot of people as part of normal human variation. People who used to be labeled as broken are now talking about their brains like they’re unique, not defective. And they’re not wrong. Recent studies suggest that up to 30% of the population may be neurodivergent7 in one way or another. There are TikTok creators making videos about how their “ADHD brain” does something totally weird but also relatable. There are whole communities built around sharing hacks and experiences. And some of that stuff is genuinely helpful and eye-opening. In fact, peer-led mental health communities online are now used by 42% of teens and young adults8, and those who use them report higher rates of feeling understood than from traditional clinical care. But also, let’s be honest: it’s gotten a little trendy. Does every quirky trait have to come with a label now? Are we really turning every personality type into a diagnosis? Because at some point, if everyone’s neurodivergent, then no one is. We’ve reached a point where even job applications ask if you need “neurodivergent accommodations,” and LinkedIn influencers casually mention their executive dysfunction like it’s a résumé booster.

That brings us to the real question everyone’s too afraid to ask out loud: is this whole neurodivergence thing a passing fad or are we living through a mental health renaissance? And before anyone yells, let’s just remember that we’ve had fads before. There was the gluten-free boom of 2012, when suddenly 45% of brunch menus came with quinoa and shame9. There was the crystal craze, where people genuinely believed amethyst would heal their taxes. There was the raw food movement, essential oils for literally everything, the obsession with minimalism that made everyone throw out their couches, and let’s not forget 2016’s brief but passionate affair with adult coloring books.

And mental health has had its own rotating door of trends. We once believed hysteria came from a “wandering uterus” and treated it with ice baths, orgasms, or removing half your insides. Lobotomies were all the rage in the 1940s. By 1951, over 18,000 Americans had been lobotomized10, often for things like depression, anxiety, or just being inconvenient. Rosemary Kennedy, yes, of the famous Kennedy family, was lobotomized at 23 for mood swings and mild rebellion. The result was catastrophic. She was left with the mental capacity of a two-year-old and hidden away for the rest of her life. Actress Frances Farmer was institutionalized and allegedly lobotomized after challenging Hollywood and her mother too many times. There was also Howard Dully, who was lobotomized at age twelve because his stepmother described him as “defiant.” Spoiler alert: he was just a normal preteen with an attitude. Psychiatry has never been immune to trends. It just tends to dress them up in lab coats and call them “breakthroughs.”

And so of course we ask: do we even need psychiatrists anymore? Has the field become obsolete, a relic from a time when people weren’t allowed to Google their own symptoms at 2 a.m. while panic-eating crackers? The Church of Scientology would say yes, and also that we’re evil, which is rich coming from a group founded by a sci-fi writer who thought trauma came from space volcanoes. But setting that aside, it’s a fair question. With AI therapists now offering 24/7 support in 200 languages12, apps like Woebot and Wysa pulling in millions of users, and virtual CBT platforms popping up faster than skincare brands, it’s natural to wonder if the whole profession is getting ChatGPT’d into irrelevance. But here’s the thing. As of now, 68% of people still say they prefer a human therapist to a digital one11, and outcomes tend to be significantly better when there’s actual human empathy involved. That’s something AI can’t fake, no matter how many emojis it uses. And let’s be real. AI might be great at reminders and journaling prompts, but it still can’t say “hmm” with that soul-piercing intensity that makes you rethink your entire childhood.

Plus, it’s not just psychiatry that’s changing. It’s the world we live in. We’re in a culture that is basically optimized for disconnection. You can grocery shop, work, date, game, argue, and even go to church online without speaking to a single real person. The average American now spends more than seven hours a day on screens13, loneliness rates are at an all-time high14, and only 16% of people report feeling “very connected” to their community15. Even families eat together less than half as often as they did in 1990. It’s like the whole system was designed to help us stay in pajamas and never form a single new friendship again. Mental health treatment is one of the only places where people still talk face to face about their lives without having to hashtag it afterward. That’s probably worth keeping around.

So maybe neurodivergence is the real deal. Maybe psychiatry is still essential. Maybe therapists, flawed as they are, represent one of the last socially acceptable ways to feel known in a world full of pop-ups, prescriptions, and three-second attention spans. Or maybe we’re just rearranging the deck chairs on the S.S. Burnout. Either way, the rules are changing, and we’re all just trying to figure it out, one meltdown, diagnosis, and trending hashtag at a time.

If you want to discuss this with me, please reach out through my website: harrison@boulderpsychiatryassociates.com.

Footnotes

- Movement Advancement Project. (2023). LGBTQ+ Mental Health Disparities Report. ↩

- Ghandour, R. M., et al. (2019). “Prevalence and Treatment of Mental Disorders in U.S. Children.” JAMA Pediatrics, 173(11), 1129–1137. ↩

- Danielson, M. L., et al. (2022). “Trends in Parent-Reported Medication Use for ADHD.” National Health Interview Survey, CDC. ↩

- CDC. (2023). “Data and Statistics on ADHD.” ↩

- Bitsko, R. H., et al. (2018). “Mental Health Surveillance Among Children.” MMWR, 67(6), 1–27. ↩

- U.S. Department of Education. (2021). Civil Rights Data Collection. ↩

- Baron-Cohen, S. (2020). “The Concept of Neurodiversity.” Autism, 24(8), 1945–1949. ↩

- Rideout, V., & Fox, S. (2018). Digital Health Practices, Social Media Use, and Mental Well-Being Among Teens and Young Adults. Hopelab. ↩

- Consumer Reports. (2014). “The Gluten-Free Boom.” Consumer Reports Magazine, August 2014. ↩

- El-Hai, J. (2005). The Lobotomist. John Wiley & Sons. ↩

- APA. (2023). “Public Perceptions of Digital Therapy.” American Psychological Association Survey Report. ↩

- Miner, A. S., et al. (2016). “Talking to Machines About Mental Health.” Journal of Medical Internet Research, 18(6), e153. ↩

- Nielsen. (2023). Total Audience Report, Q3 2023. ↩

- Cigna. (2020). Loneliness in America: Survey Results. Cigna White Paper. ↩

- Pew Research Center. (2021). “Community and Social Connection Survey.” ↩