OCD officially packed its bags and moved out of the Anxiety Disorders “house” in 2013 when the DSM-5 came out1. Before that, it lived with all the other anxious conditions, but the experts decided OCD was just too unique to be lumped in2. Now it lives in its own fancy neighborhood called “Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders” along with other quirky conditions like hoarding and hair pulling3.

Before and after 2013, the numbers for OCD stay pretty steady at about 1.2 percent of U.S. adults in a given year and around 2 to 3 percent over their lifetime4. It is the same group of people, just rebranded into a fancier diagnostic category. What did change is the headcount for the broader “OCRD” family, which now includes OCD’s distant cousins like body dysmorphic disorder, skin picking, and trichotillomania5. Together they make up over 9 percent of the population, which is way more than OCD alone, but that is because the guest list got bigger, not because OCD suddenly went viral.

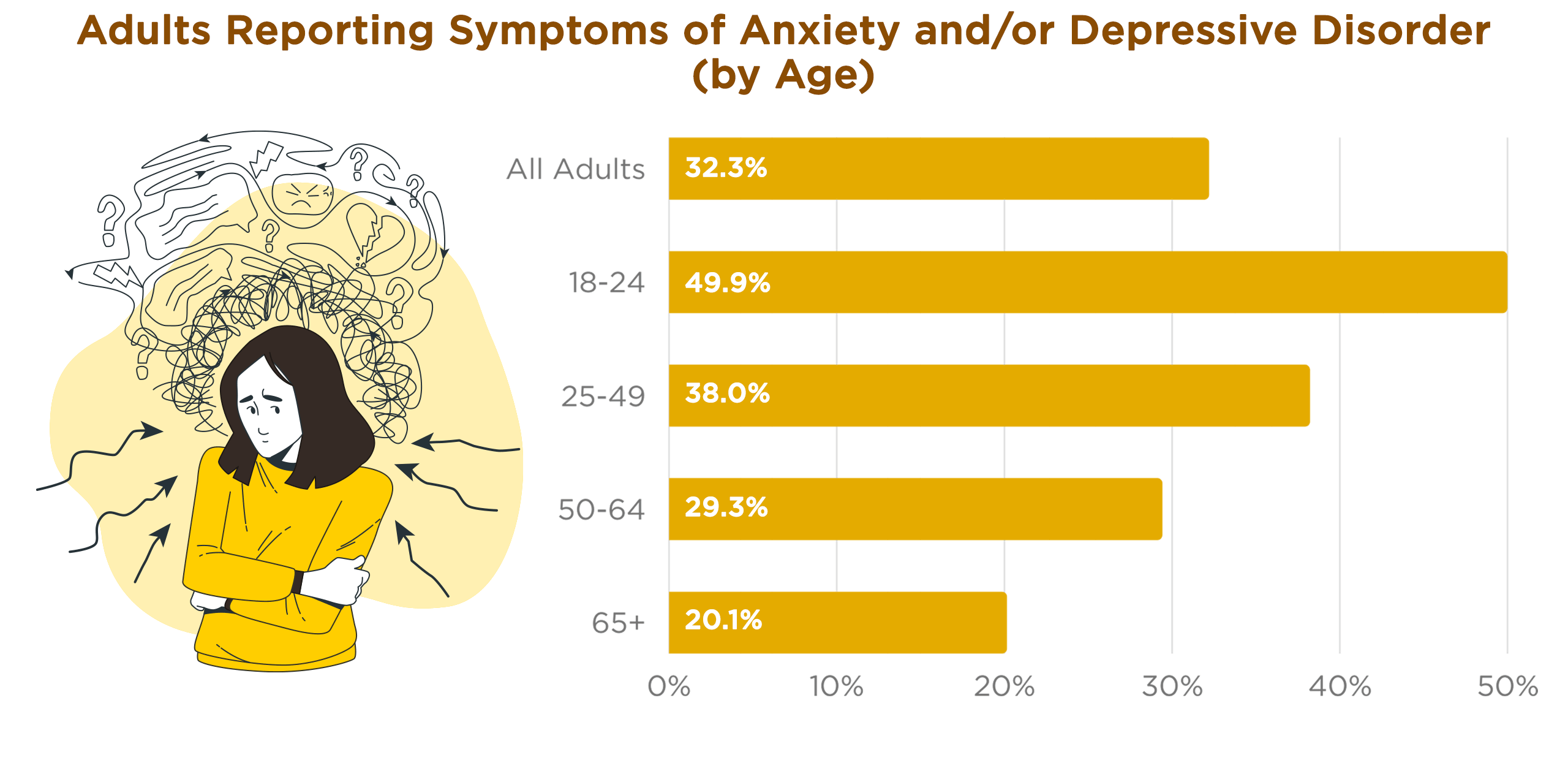

If we zoom out to anxiety in general, about 19 percent of U.S. adults meet criteria for an anxiety disorder in any given year and roughly 31 percent will meet criteria at some point in their lives6. Among teenagers, the numbers climb even higher with nearly 32 percent of adolescents meeting criteria for an anxiety disorder, and girls are affected at almost twice the rate of boys7. A hundred years ago, we do not have directly comparable statistics because the categories and measurement tools did not exist, but anxiety was definitely around.

Anxiety just wore different names like “neurasthenia” or “anxiety neurosis”8. And people back then still wanted something to calm their nerves. By 1957, over 7 million Americans had taken Miltown (also known as meprobamate, a prescription tranquilizer that became available in the US market in 1955) and by the late 1970s, Americans were swallowing over 2 billion Valium tablets a year9. Hence, the song, “Mother’s Little Helper”, by the Rolling Stones. Large-scale epidemiological studies only became standard in the 1990s, so some of the increase we see today may be because we are actually measuring it better and people feel less embarrassed admitting it10. But even with that in mind, surveys since the mid 2000s show anxiety is truly more common now, especially in adolescents and young adults.

If we think about OCD’s removal from the anxiety category in 2013, it is possible that a small slice of people who say they have anxiety today actually meet criteria for OCD. Based on the numbers, up to 1 to 2 percent of the population reporting anxiety could actually be describing OCD symptoms that now have their own category. Since research suggests that more than half of people with OCD also have another anxiety disorder, the overlap is messy. It is no wonder people throw the word “anxiety” around like it is a universal label for feeling tense, fearful, or restless, even if that is not technically what they have.

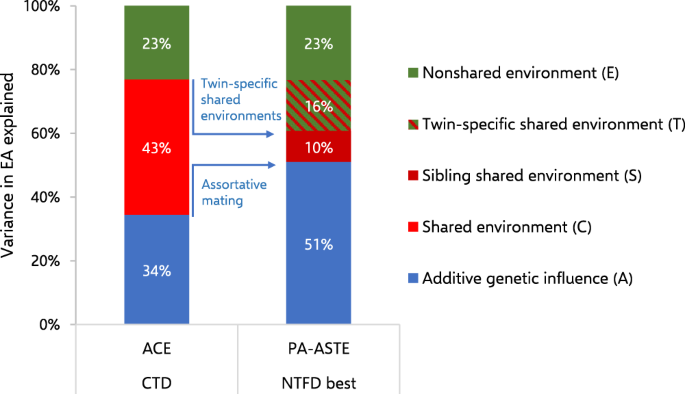

If you have a first-degree relative with OCD, your own risk is about two to three times higher than average, and if their symptoms started in childhood, that number goes up even more. Twin studies back this up with heritability estimates hovering around 45 to 65 percent, meaning genes explain a big chunk but not all of the risk. OCPD also runs in families, with studies suggesting heritability rates between 27 and 78 percent depending on how strictly you define it. Families also pass down more than DNA. The offspring of these adults likely “pick up” habits which are understood as “normal”.

Trauma, especially abuse, is another ingredient that can shape whether OCD or OCPD develops. People who experience physical, sexual, or emotional abuse in childhood have a significantly higher risk of developing OCD, with some research showing the odds can be two to three times greater than in those without such histories. One meta-analysis found that 30 to 40 percent of adults with OCD reported some form of childhood abuse. OCPD also has links to early abuse and harsh or overly controlling parenting styles. One large-scale study found that people reporting childhood emotional abuse were nearly twice as likely to develop OCPD, possibly because rigid control and perfectionism become survival strategies when unpredictability and criticism are constant. Abuse does not guarantee either condition, but when you mix it with genetic vulnerability and certain personality traits, you get a pretty solid recipe.

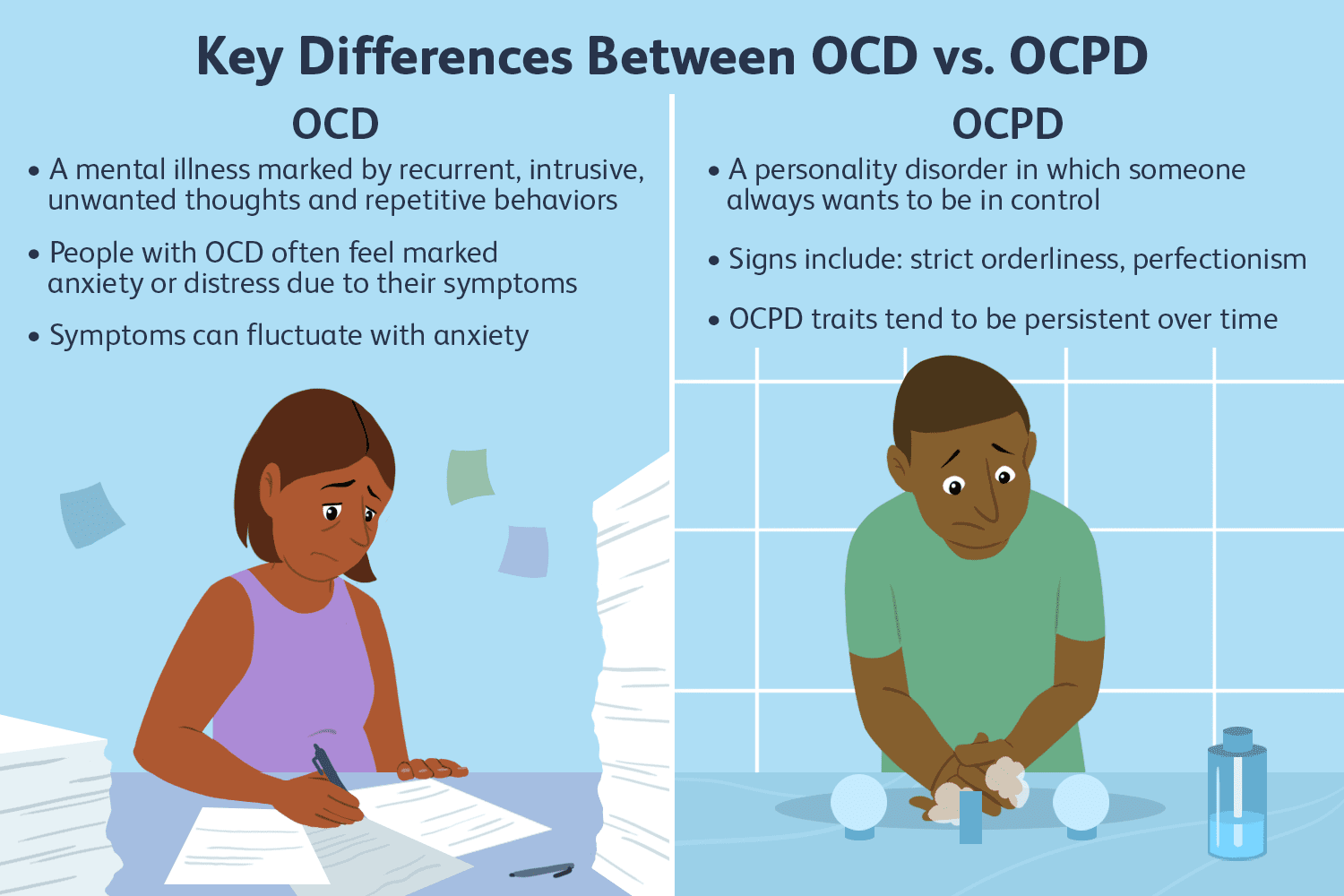

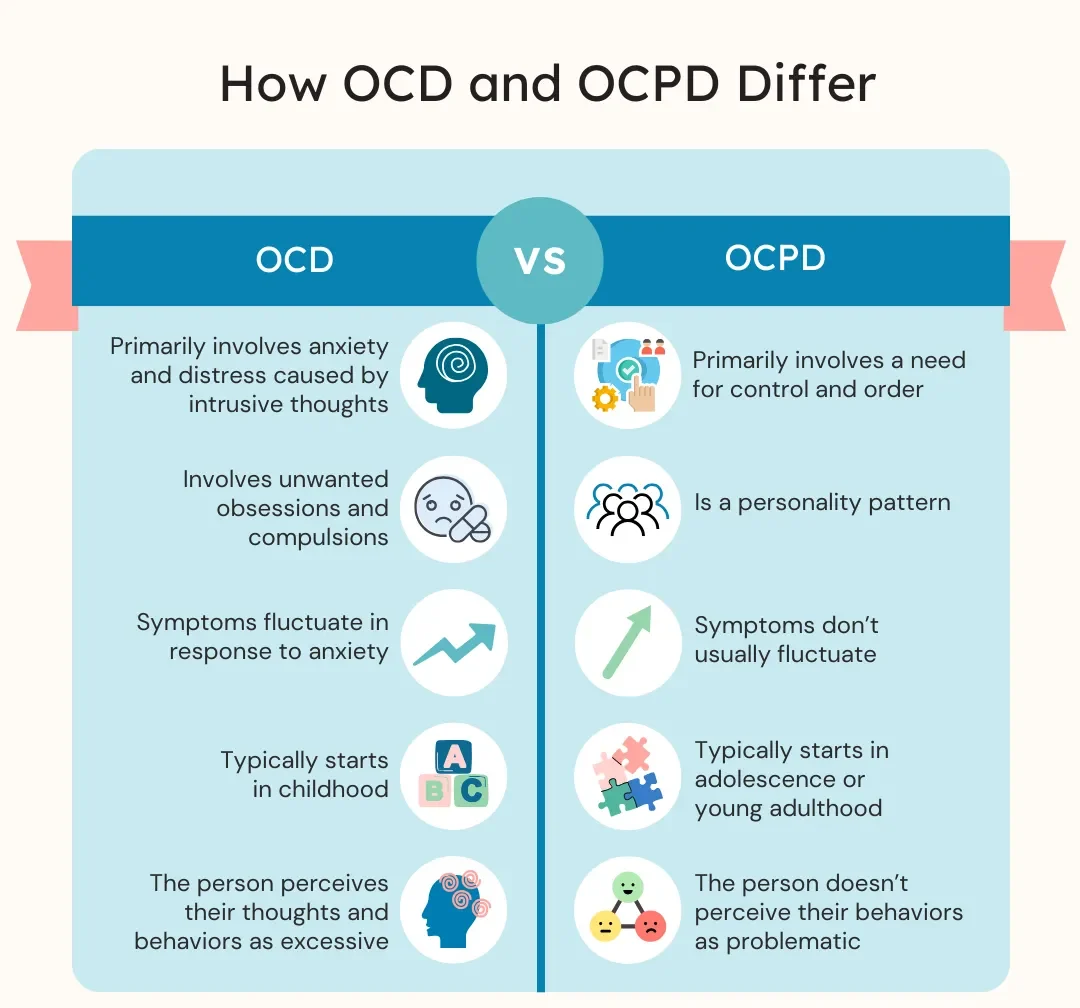

The difference between OCD and OCPD is like the difference between being haunted by intrusive thoughts and rituals versus being convinced that your way is the only correct way and everyone else is a slob and you don’t understand them. OCD is about unwanted thoughts or images popping into your head, called obsessions, and then doing something over and over to calm the anxiety, called compulsions. People with OCD usually know their rituals make no logical sense, can be seen by others as “funny quirks’, but the anxiety makes them do it anyway. OCPD is a personality disorder, which means it is not about isolated symptoms but an enduring and inflexible pattern of thinking, feeling, and behaving that shapes a person’s whole life. With OCPD, the rules, order, perfectionism, and control are not seen as a problem by the person who has them. In fact, they often think everyone else should be more like them. If OCD is about escaping the thoughts, OCPD is about living in a fortress built out of them.

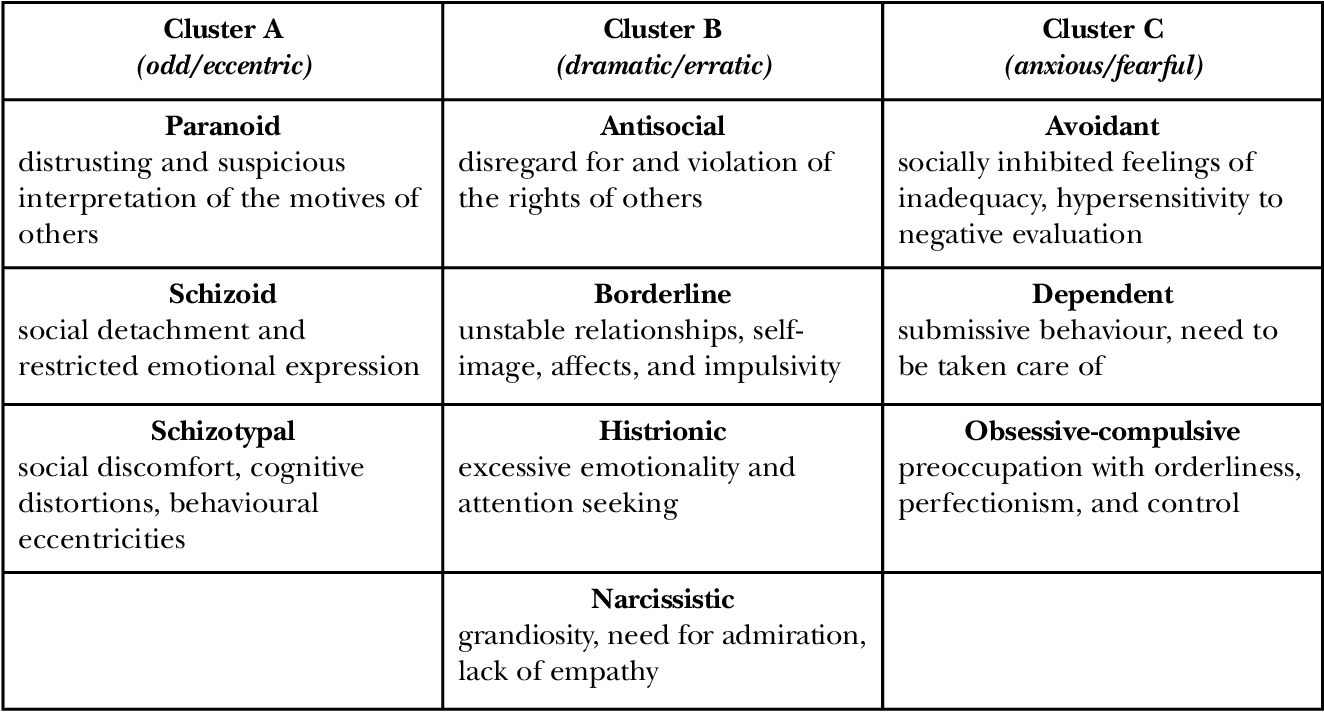

Personality disorders as a group are long-standing patterns of traits and behaviors that cause distress or problems in relationships, work, or other areas of life11. They are organized in the DSM into clusters. Cluster A covers odd or eccentric patterns. Cluster B includes dramatic or erratic ones like borderline or narcissistic personality disorder12. Cluster C holds the anxious or fearful ones, which is where OCPD lives alongside avoidant and dependent personality disorders.

Yes, a person can have more than one personality disorder at the same time. This is called comorbidity and it is common13. Some studies suggest that over 50 percent of people diagnosed with one personality disorder meet criteria for at least one more. You can be diagnosed with both borderline personality disorder and OCPD, which is like living with a constant tug-of-war between emotional volatility and rigid control. Other combinations exist too, like narcissistic personality disorder with antisocial personality disorder (ie, Trump), or avoidant personality disorder with dependent personality disorder. Sometimes the traits blur together and sometimes they just sit there side by side like bad roommates.

While personality disorders can be deeply ingrained, they can be helped14. Treatment often takes longer than with things like depression or panic disorder and focuses on increasing insight, improving flexibility, and building healthier coping strategies rather than trying to erase the personality structure entirely.

There are also other ways of looking at both OCD and OCPD besides the DSM checklist. Some psychologists describe OCD as a kind of mental allergy where harmless thoughts get flagged as dangerous, triggering compulsions like pollen triggers sneezing. OCPD can be seen less as an illness and more as a fixed personality strategy, an overdeveloped survival skill that once kept life under control but now strangles flexibility.

More dynamic views go deeper into the emotional roots. From that angle, both OCD and OCPD can be elaborate attempts to create order and predictability in a world that feels chaotic or unsafe15 (ie, the US currently). For someone with OCD, the rituals might feel like the only barrier between themselves and disaster. For someone with OCPD, strict rules and control over every detail can feel like the only way to keep life from unraveling. Both can be coping systems born out of an intense need to regain mastery when life has delivered a heavy dose of powerlessness.

It is also worth noting that while both conditions can have a genetic component, they can also develop over time. OCD often begins in childhood or adolescence, sometimes triggered by stress, trauma, or even physical illness, but it can also appear later in adulthood16. About 50 to 60 percent of OCD cases begin before age 20. OCPD traits tend to develop more gradually, often solidifying in late adolescence or early adulthood, sometimes reinforced by environments that reward perfectionism and control.

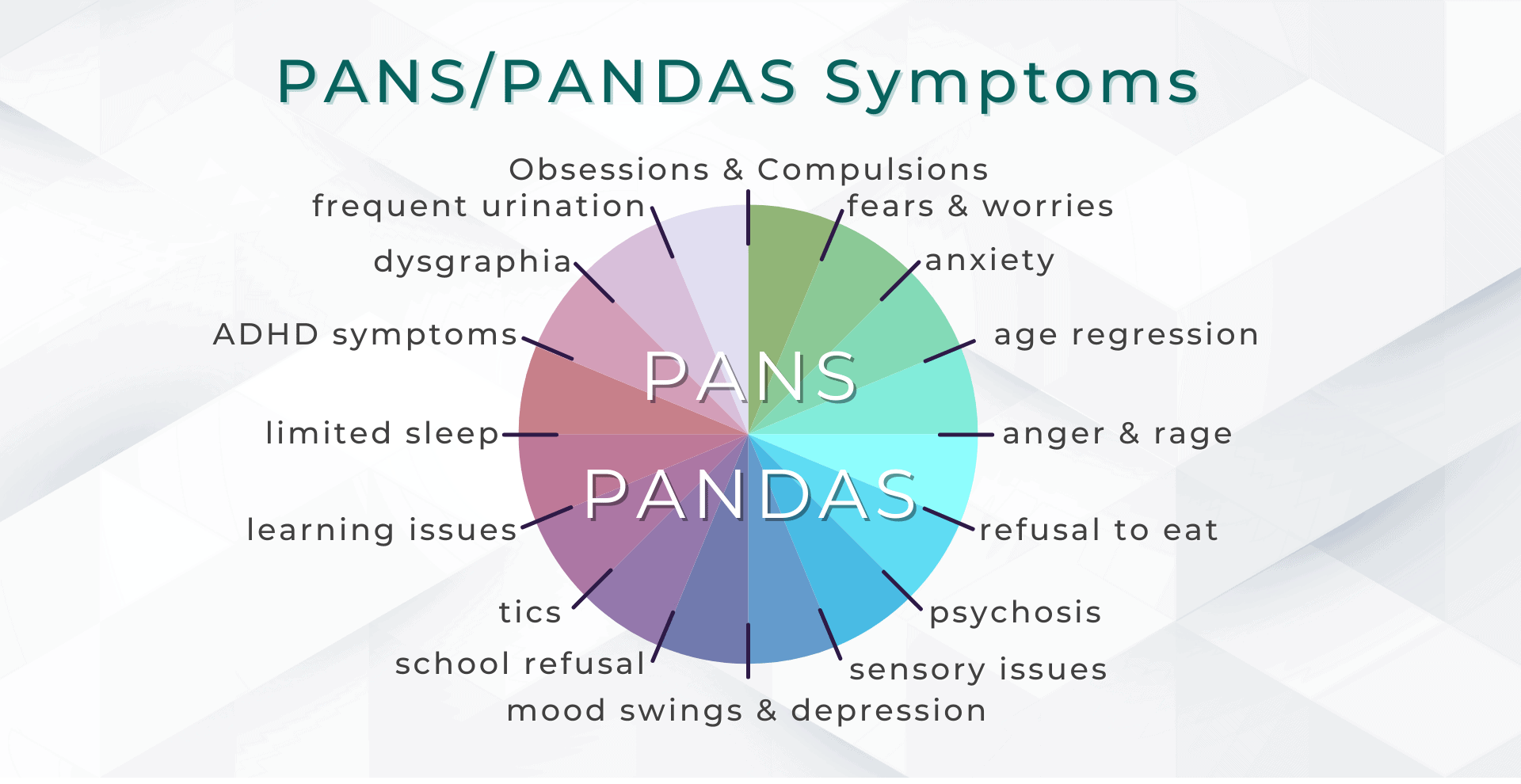

PANS (Pediatric Acute-onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome) is when a child suddenly develops OCD symptoms and sometimes other severe mood or behavior changes, often after an infection or immune reaction17. In children, it can look like OCD appearing overnight, complete with compulsions, anxiety, and even tics. Most OCD develops gradually, but PANS is the fast-track version. It often requires both psychiatric treatment and medical interventions to address the underlying cause. Some research suggests that up to 1 in 200 children may have a PANS or PANDAS (Pediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorders Associated with Streptococcal Infections) episode. It is one of the few OCD scenarios where a strep test and antibiotics might be part of the recovery plan.

It is also worth sorting out how OCD and OCPD differ from addictions18. While they can all look repetitive and hard to stop, the reasons behind them are different. OCD behaviors are done to relieve anxiety from an unwanted thought. OCPD behaviors are done because the person believes their way is the correct and necessary way to do things. Addictions are about seeking pleasure or relief from withdrawal by using a substance or engaging in a rewarding behavior even when it causes harm. The OCD sufferer washes their hands for the tenth time because their brain is screaming about germs. The person with OCPD alphabetizes the spice rack because that is the right way. The person with an addiction keeps using because their brain’s reward system has been hijacked and stopping feels worse than continuing.

OCD likes company. It often shows up with depression, other anxiety disorders, and sometimes tics or Tourette’s19. It is also pretty friendly with eating disorders, which show up in about 17 percent of people with OCD. OCPD’s usual companions include depression, anxiety, and sometimes other personality disorders. These two are not shy about double booking themselves in your brain. OCD carries a very real risk for suicidal thoughts and suicide attempts, with more than half of people with OCD reporting suicidal thoughts and about one in four attempting suicide at least once. The risk is about twice as high when OCD is paired with major depression. OCPD’s suicide risk is lower but not zero, especially when its perfectionism and rigidity feed depression.

It is also helpful to separate OCD and OCPD from other mental health experiences that can look intense but have different engines running the show20. Gender dysphoria is not about repetitive thoughts or rigid control over order and rules. It is distress that comes from a mismatch between someone’s experienced gender and their assigned sex at birth, and the distress often decreases when they can live in a way that reflects their identity. Impulsiveness, whether part of ADHD, bipolar disorder, or its own disorder, is about acting quickly without thinking about consequences. That is the opposite of OCD’s hesitation and OCPD’s overthinking. Joining a cult is also different. While it may involve rigid rules or repetitive rituals, it is usually driven by social pressure, charismatic authority, and sometimes manipulation or isolation, not the inner cycle of anxiety and compulsion that defines OCD or the deeply ingrained control style of OCPD.

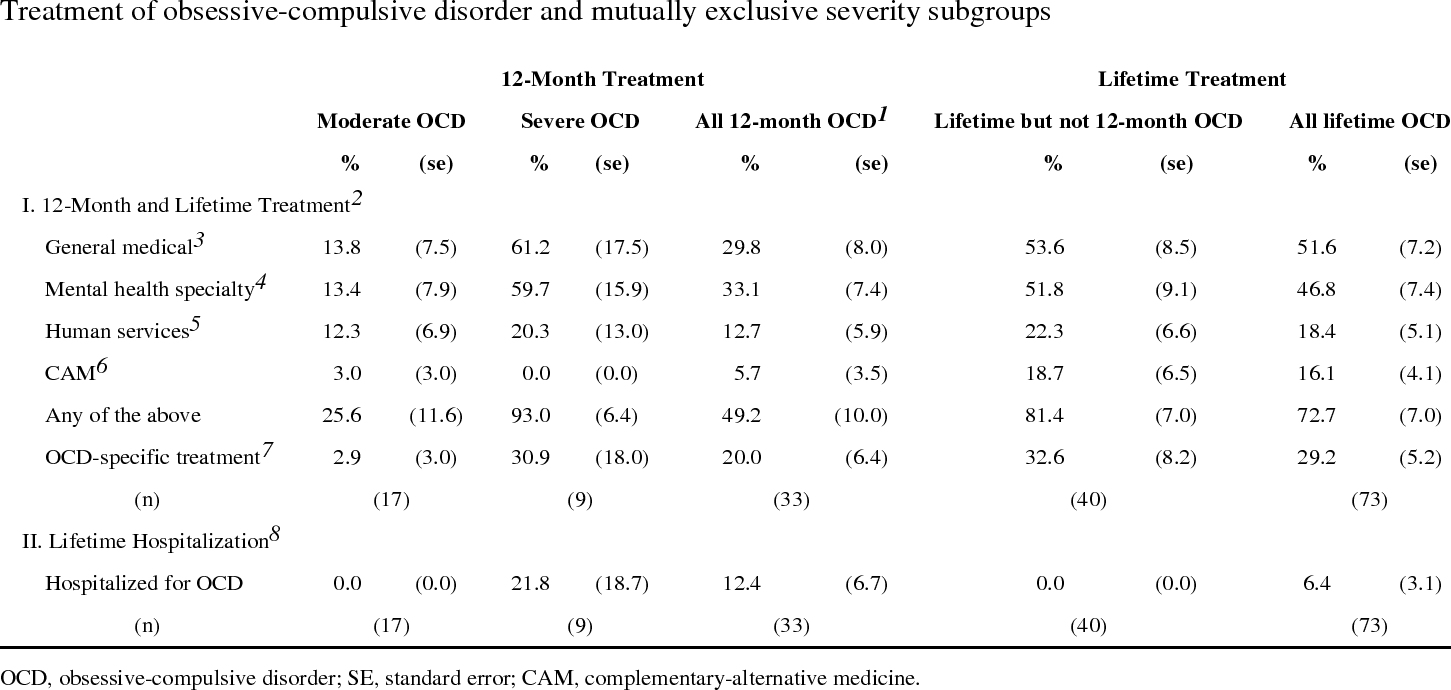

OCPD is still one of the most common personality disorders, generally estimated at about 3 percent of the population, with some studies putting it closer to 8 percent. Helping OCD involves therapy, especially Exposure and Response Prevention, which is like a controlled and professional version of “face your fears and do not do the thing you want to do.” Medications like SSRIs are also used, usually at higher doses than for regular depression.

For OCPD, the strategy is more about long-term therapy to help the person be less rigid and more open to other ways of doing things. Personality disorders in general can be treated, but the process is longer and focuses on building insight, loosening rigid patterns, and strengthening relationships rather than deleting the personality structure entirely. Addictions need a totally different plan, focusing on breaking the reward craving cycle through therapy, support groups, sometimes medication, and always a plan for triggers. Gender dysphoria treatment may involve gender-affirming care and therapy that supports identity. Impulsiveness can be addressed with self-regulation strategies, sometimes medication, and reducing environmental triggers. People leaving cults often benefit from deprogramming, trauma-informed therapy, and rebuilding social support outside the group. PANS-related OCD might require both psychiatric and medical treatment to settle symptoms and treat the physical cause.

So, in short, OCD and OCPD are like two very different relatives who just happen to have similar last names, addictions are the neighbor who throws loud parties you cannot seem to stop going to even though you know you will regret it the next morning, gender dysphoria is the roommate who just wants to be seen for who they are, impulsiveness is the friend who buys a car on a whim, cult membership is like getting trapped at the worst group retreat in history, and PANS is like a sudden storm that blows in overnight and rearranges the furniture in your brain.

One knows it has a problem and wants help to stop the cycle. Another thinks the problem is everyone else and would prefer the world adjust accordingly. One keeps going back for more because their brain insists it is the best idea ever. The other is about aligning identity with reality. One is about slowing down before acting. The other is about escaping control that was never truly yours. And one is about fighting an infection before you can even think about the mental patterns it set in motion.

All can be helped, but the playbook depends on which one you are dealing with. Neither OCD nor OCPD has gotten more popular in the past decade. They are just living in slightly different parts of the DSM neighborhood, passing along both their DNA and their quirks to the next generation, and in some cases passing along a risk of feeling so trapped that thoughts of ending it start to seem like the only way out. And for many with OCD or OCPD, whether you explain it through biology, learned patterns, abuse histories, immune system flare-ups, or deeper psychological defenses, it often comes down to building a fortress of order in the middle of life’s chaos, only to discover that the fortress can become a prison if you never learn to open the gates.

If this piece brought up anything for you that concerns you, or if you have any questions, please contact me through my website: https://boulderpsychiatryassociates.com. More often than not these types of issues (OCD/OCPD) are best seen by others, not by yourself.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. ↩

- Stein, D. J., Fineberg, N. A., & Bienvenu, O. J. (2010). Should OCD be classified as an anxiety disorder in DSM-V? Depression and Anxiety, 27(6), 495–506. ↩

- Phillips, K. A., Stein, D. J., Rauch, S. L., Hollander, E., Fallon, B. A., Barsky, A., … & Simeon, D. (2010). Should an obsessive–compulsive spectrum grouping of disorders be included in DSM-V? Depression and Anxiety, 27(6), 528–555. ↩

- Ruscio, A. M., Stein, D. J., Chiu, W. T., & Kessler, R. C. (2010). The epidemiology of obsessive–compulsive disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Molecular Psychiatry, 15(1), 53–63. ↩

- Lochner, C., & Stein, D. J. (2010). Obsessive–compulsive spectrum disorders in obsessive–compulsive disorder: A review. CNS Spectrums, 15(5), 284–291. ↩

- National Institute of Mental Health. (2022). Any anxiety disorder. ↩

- Merikangas, K. R., He, J. P., Burstein, M., et al. (2010). Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey–Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(10), 980–989. ↩

- Shorter, E. (1992). From paralysis to fatigue: A history of psychosomatic illness in the modern era. New York: The Free Press. ↩

- Herzberg, D. (2009). Happy pills in America: From Miltown to Prozac. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. ↩

- Twenge, J. M., & Joiner, T. E. (2020). Mental distress among U.S. adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 76(12), 2170–2182. ↩

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Personality disorders. In Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. ↩

- Skodol, A. E., & Bender, D. S. (2009). Why are women diagnosed borderline more than men? Psychiatric Quarterly, 80(4), 349–362. ↩

- Zimmerman, M., & Coryell, W. (1989). DSM-III personality disorder diagnoses in a nonpatient sample. Archives of General Psychiatry, 46(8), 682–689. ↩

- Clarkin, J. F., & Livesley, W. J. (2016). An integrated approach to the treatment of personality disorder. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 26(1), 3–18. ↩

- Salzman, C. (1998). Obsessive–compulsive personality disorder: A review of current literature. Journal of Personality Disorders, 12(3), 216–230. ↩

- Taylor, S. (2011). Obsessive–compulsive disorder: Theory, research, and treatment. New York: Guilford Press. ↩

- Swedo, S. E., Leckman, J. F., & Rose, N. R. (2012). From research subgroup to clinical syndrome: Modifying the PANDAS criteria to describe PANS (pediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome). Pediatrics & Therapeutics, 2(2), 113. ↩

- Potenza, M. N. (2006). Should addictive disorders include non-substance-related conditions? Addiction, 101, 142–151. ↩

- Fineberg, N. A., Sharma, P., Sivakumaran, T., Sahakian, B., & Chamberlain, S. R. (2007). Does obsessive–compulsive disorder qualify as an addiction? Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 9(3), 267–279. ↩

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Gender dysphoria. In Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. ↩