A Hundred Years of Worry

Every generation of kids has been anxious. The triggers and the parenting styles just kept changing with the times. In 1918 the Spanish flu killed about 50 million people worldwide1, and a ten-year-old could easily lose a sibling overnight. Nearly one in five American kids under 16 worked full time jobs2. Of course they were anxious. But people didn’t call it anxiety, they called it weak nerves or hysteria or just life. Parents weren’t focused on feelings. Their job was to keep the kids alive and fed, and if they cried too much, they were sent outside to toughen up. George Carlin once joked that back then, “We didn’t have childproof caps because kids weren’t stupid enough to eat bleach.”3

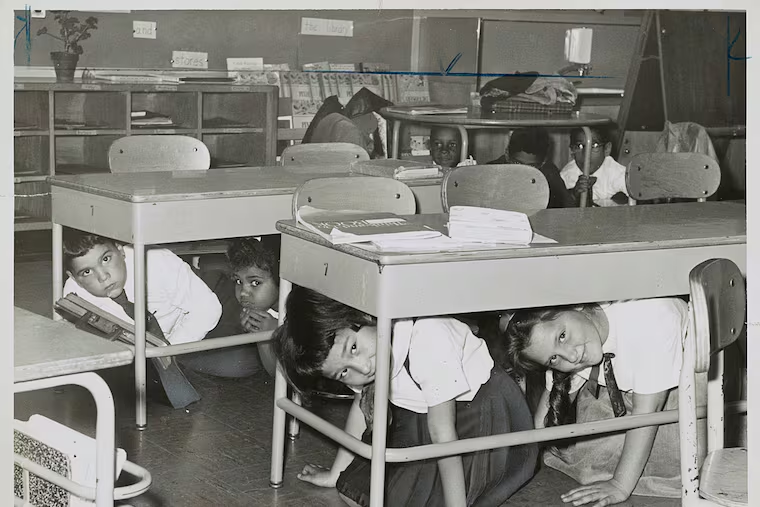

Duck and Cover Childhoods

By the 1950s and 60s forty million kids practiced duck and cover nuclear bomb drills under their desks4. Anxiety was rising, but the word still wasn’t being used. The government called it “juvenile delinquency” and even held Senate hearings in 19545. Parents weren’t especially involved either. Only about 20 percent of dads even played regularly with their kids6. If you said you were nervous, the answer was a cigarette, a stiff drink, and the advice to toughen up. Bill Burr has a line that captures this era: “Back in the day, your dad didn’t care if you were sad—he just told you to rub some dirt on it and stop crying before he gave you something to cry about.”7

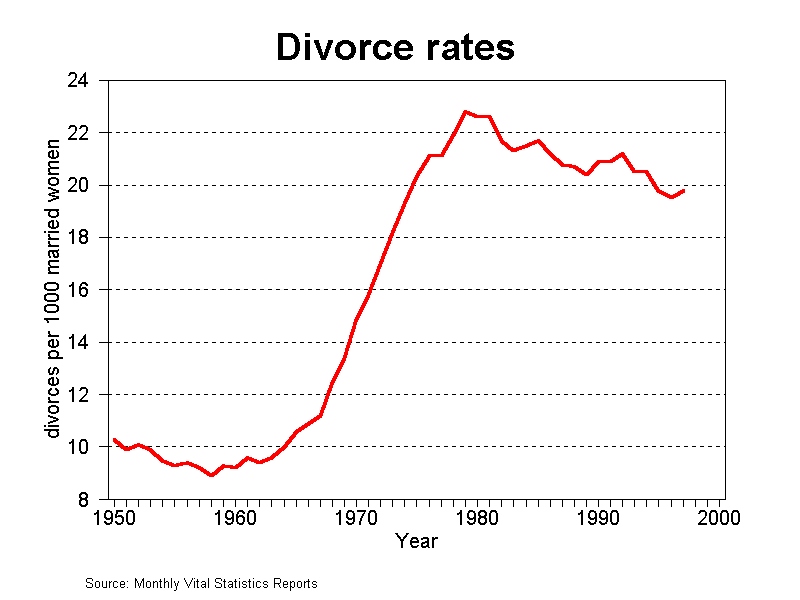

Latchkey Loneliness

The 70s and 80s looked different. Divorce rates doubled between 1960 and 19808, which meant 40 percent of kids had divorced parents by the mid 80s9. More moms were working, and by 1984 five million American kids were officially latchkey kids10. They let themselves into empty houses every afternoon. Anxiety showed up as loneliness, eating disorders tripled11, and depression arrived earlier than ever. Still, the DSM lagged behind, offering categories like school refusal or conduct disorder. Parenting here was a blend of benign neglect and microwaved dinners. Marc Maron likes to say, “My parents weren’t checking my homework—they were barely checking if I was home.”12

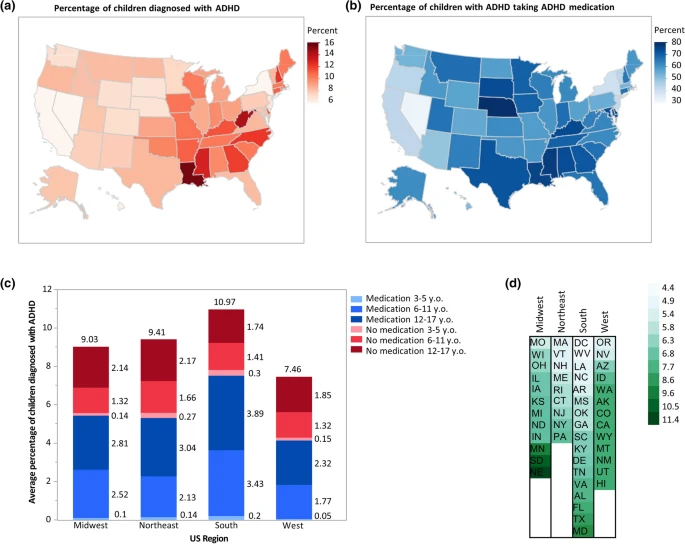

Helicopters Take Flight

The 1990s and 2000s brought helicopter parenting. Childhood became a résumé competition. Between 2003 and 2007 anxiety diagnoses doubled13. By 2011, 11 percent of kids carried an ADHD diagnosis14. Parents were suddenly omnipresent, hovering at soccer practice, emailing teachers, and auditing every homework assignment like quality inspectors. Anxiety flourished, because now kids weren’t just supposed to survive school, they were supposed to ace it. The I’ve Had It podcast would call this what it is: parents acting like “their kid is a start-up company that just needs more venture capital.”15

Bulldozers at Work

Now we’re in the bulldozer era. Parents don’t just hover, they clear the road entirely, flattening every obstacle in advance. Anxiety and depression are everyday teen vocabulary. By 2019 nearly one in three adolescents had an anxiety disorder16. After COVID, 42 percent of high schoolers reported feeling persistently sad or hopeless, and 22 percent said they had seriously considered suicide17. 95 percent of teens have a smart phone, with screen time averaging 8 to 10 hours a day18, and you get a generation marinating in a stew of climate change, school shootings, political chaos, and social media comparisons. Kids don’t just have anxiety anymore, they brand it. “I can’t go, I have social anxiety.” “I stayed up till 3, that’s my ADHD.” George Carlin once said, “We’ve added more names to things that already existed, but no one’s actually any tougher.”19 That’s today’s vibe in a sentence.

So Is This the Worst Era?

Historically, no. The Black Plague and World War II still win the “worst childhood environment” award20. But this is the loudest and most relentless era. There’s no break. Not at school, not online, not even at home, where parents are micromanaging futures. Each generation has been anxious, but the volume keeps rising and the spotlight keeps getting harsher.

In 1920 your kid was lazy. In 1960 your kid was delinquent. In 1980 your kid was lonely. In 2000 your kid was a diagnosis waiting to happen. And in 2025? Your kid is frozen, anxious, and possibly livestreaming it.

How to Help the Frozen Generation

Which brings us to the practical part: what can actually be done? Because yelling “just go to school” at a frozen teenager works about as well as telling someone with a broken leg to run a marathon. The climb has to start smaller. Sometimes it begins with waking up at a regular time. Then maybe just driving to the school parking lot. Then sitting in class for one period. Then building up slowly. This is exposure therapy in slow motion, and the research shows it works: up to 70 percent of kids with school refusal can successfully return when exposure-based CBT is applied consistently21.

Many of these kids also have reversed their days and nights. They are awake at 3 a.m. and sleep until noon. That isn’t laziness, it’s biology gone haywire. Resetting a teenager’s body clock isn’t an overnight fix. It takes gradual changes: light therapy, melatonin, exercise, and consistency. Sleep is one of the fastest ways to lower baseline anxiety, and studies show that even a one-hour improvement in sleep can cut anxiety symptoms by nearly 30 percent22.

Parents also need coaching. Anxious parents make anxious kids. If a parent is terrified of a child’s meltdown, the child learns that the meltdown is indeed a monster. Parents have to practice calm, consistency, and firmness without sliding into drill sergeant mode or doormat mode. The middle ground is hard, but it’s where progress happens. Bill Burr said, “If you coddle a kid too much, they’re twenty-three and afraid to order food without you.”23

Therapy works. Cognitive behavioral therapy is the gold standard, and large studies show that about 60 to 70 percent of anxious kids improve significantly with CBT24. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy is another good fit, teaching kids they can feel scared and still do what matters. If trauma is at the root, trauma-focused therapy is essential. And yes, sometimes medication helps. SSRIs don’t magically solve avoidance, but they lower the baseline anxiety enough to make therapy possible. About 55 to 65 percent of kids respond well to SSRIs for anxiety, especially when combined with therapy25.

Technology is both the villain and the unlikely sidekick. Gaming and scrolling at 3 a.m. lock kids in their rooms, but telehealth and online schooling can be stepping stones. Therapy might begin on Zoom, then move to in-person. Online classes can keep grades afloat while reentry happens. Tech can be a bridge instead of a trap26.

Adults who won’t leave the house face the same principles. Exposure in tiny steps, sometimes medication, sometimes peer groups. The difference is no one’s mom is dragging them out of bed anymore. They have to build their own scaffolding of accountability. The universal truth is this: avoidance makes anxiety bigger and facing it makes it shrink. As Marc Maron likes to put it, “Fear doesn’t go away—you just get used to carrying it around while you do stuff anyway.”27\

The Hopeful Ending

Helping kids or adults who are stuck is never quick. It means tackling avoidance, biology, and family systems all at once. It’s messy and slow, and progress often feels like two steps forward and one step back. But it works. Kids do return to school. Adults do reclaim their lives. The hardest part is cracking the frozen shell of paralysis so movement can start again. And once it does, history repeats itself in the best way. Anxious kids adapt, grow up, and then complain about how anxious the next generation looks.

References

- Barry, John M. The Great Influenza: The Story of the Deadliest Pandemic in History. Viking, 2004, p. 374. ↩

- Trattner, Walter I. Crusade for the Children: A History of the National Child Labor Committee and Child Labor Reform in America. Quadrangle Books, 1970, p. 112. ↩

- Carlin, George. Brain Droppings. Hyperion, 1997, p. 56. ↩

- Boyer, Paul. By the Bomb’s Early Light: American Thought and Culture at the Dawn of the Atomic Age. University of North Carolina Press, 1994, p. 214. ↩

- U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency. Hearings Before the Subcommittee to Investigate Juvenile Delinquency. U.S. Government Printing Office, 1954. ↩

- Pleck, Joseph H. The Myth of Masculinity. MIT Press, 1981, p. 92. ↩

- Burr, Bill. Let It Go. Comedy Central Records, 2010. ↩

- Cherlin, Andrew J. Marriage, Divorce, Remarriage. Harvard University Press, 1992, p. 57. ↩

- Furstenberg, Frank F. Divided Families: What Happens to Children When Parents Part. Harvard University Press, 1983, p. 33. ↩

- Belle, Deborah. The After-School Lives of Children: Alone and With Others While Parents Work. Lawrence Erlbaum, 1999, p. 21. ↩

- Brumberg, Joan Jacobs. Fasting Girls: The History of Anorexia Nervosa. Vintage, 2000, p. 189. ↩

- Maron, Marc. Attempting Normal. Spiegel & Grau, 2013, p. 45. ↩

- Merikangas, Kathleen R., et al. “Lifetime prevalence of anxiety disorders in U.S. adolescents.” Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, vol. 49, no. 10, 2010, pp. 980–989. ↩

- Visser, Susanna N., et al. “Trends in the parent-report of health care provider–diagnosed and medicated ADHD: United States, 2003–2011.” Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, vol. 53, no. 1, 2014, pp. 34–46. ↩

- Tolpin, Jennifer Welch & Angie Sullivan. I’ve Had It Podcast. Dear Media, 2022–present. ↩

- National Institute of Mental Health. “Major Depression.” NIH, 2019. ↩

- Jones, Sarah E., et al. “Mental health, suicide, and connectedness among high school students during the COVID-19 pandemic.” MMWR, vol. 71, no. 3, 2022, pp. 56–63. ↩

- Pew Research Center. “Teens, Social Media and Technology 2022.” Pew, August 10, 2022. ↩

- Carlin, George. Napalm and Silly Putty. Hyperion, 2001, p. 113. ↩

- Ziegler, Philip. The Black Death. Harper & Row, 1969, p. 201. ↩

- Kearney, Christopher A., and Wendy K. Albano. When Children Refuse School: A Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy Approach. Oxford University Press, 2007, p. 145. ↩

- Goldstein, Abby N., and Matthew P. Walker. “The role of sleep in emotional brain function.” Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, vol. 10, 2014, pp. 679–708. ↩

- Burr, Bill. Paper Tiger. Netflix, 2019. ↩

- Kendall, Philip C., et al. “Cognitive-behavioral therapy for youth anxiety: Evidence for transportability to community clinics.” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, vol. 76, no. 1, 2008, pp. 77–85. ↩

- Walkup, John T., et al. “Cognitive behavioral therapy, sertraline, or a combination in childhood anxiety.” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 359, no. 26, 2008, pp. 2753–2766. ↩

- Holmes, Emily A., et al. “Digital mental health and pandemic resilience: Evidence, challenges, and opportunities.” World Psychiatry, vol. 20, no. 3, 2021, pp. 318–335. ↩

- Maron, Marc. WTF Podcast. Episode 543, 2014. ↩