Autism didn’t get an official name until the 1940s, which is kind of ridiculous when you think about how long girls had already been punished just for not fitting into society’s idea of what a girl should be. Basically, if you were a girl and weren’t quiet, sweet, or perfectly polite, people thought something was wrong with you. And I don’t mean they just looked at you funny. I mean they literally locked you up.

Before the 20th century, more than 70 percent of the women in U.S. institutions didn’t even have a condition that would be considered diagnosable by today’s standards. What they actually had was trauma. Or they were poor. Or they didn’t obey. But since medicine didn’t have a clue what to do with that, they just labeled it “hysteria,” which is a fancy way of saying “we don’t get why this woman is upset, so we’re going to say it’s her uterus’s fault.” No joke. The word “hysteria” comes from the Greek word “hystera,” which literally means uterus. So yes, doctors used to blame a woman’s uterus for her mental health issues.1

And sure, you won’t find doctors today writing “hysteria” on a patient chart, but let’s be honest, the attitude is still alive and kicking. Women who explain that they’re struggling emotionally are still more likely to get vague, fluffy diagnoses like anxiety or depression or “stress-related symptoms” instead of someone bothering to ask, “Hey, could this be neurodivergence?”2

So now picture this. It’s the 1940s, and two guys named Leo Kanner and Hans Asperger come along and give autism a name. Suddenly, it’s like they’ve discovered a brand-new type of human. But here’s the catch: they only really focused on boys. Leo Kanner wrote about eleven kids in his first autism study. Ten were boys. Asperger’s big study? Over two hundred children, and only four girls. This wasn’t just a coincidence or bad luck. It was science being designed around boys.3 Girls were basically invisible in autism research from day one.

And because of that, girls with autism were ignored or misdiagnosed for years. Sometimes doctors thought they had schizophrenia or depression. Sometimes no one noticed anything at all. Research from the 1960s and 70s shows that boys were eight to ten times more likely to be diagnosed with autism than girls, even when girls had the exact same behaviors.4 If a boy couldn’t sit still in class or spent hours yelling about dinosaurs, everyone jumped into action. “Take him to a doctor! Get him tested!” But if a girl acted that way? “She’s just shy. She’ll grow out of it.” What actually happened was she learned to act normal and keep it together on the outside while falling apart inside.

And while boys were getting support and therapy and all that good stuff, girls were often getting sent to hospitals or eating disorder clinics. Because instead of seeing their autism, people saw something else. They saw a problem they didn’t understand. And when people don’t understand girls, they usually blame them. That’s just how the system has worked. Girls learned to survive by pretending. They didn’t get seen. They got erased.

Real research shows that girls with autism are way more likely to be misdiagnosed. Instead of getting an autism diagnosis, they usually get slapped with something like anxiety, depression, borderline personality disorder, or the modern version of that old hysteria nonsense. They didn’t get help because they didn’t show the kind of obvious warning signs people were trained to look for. Instead of being loud or disruptive, these girls became experts at pretending.5 They studied the people around them and copied everything, from how their classmates moved to how they talked. They became little social chameleons. On the outside, they looked fine. Inside, they were on fire.

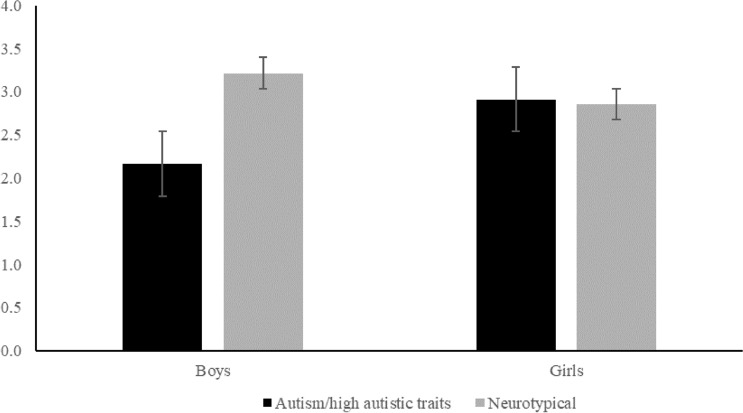

A study in 2022 by McQuaid and their team basically confirmed what autistic girls have known forever. Girls were way better than boys at camouflaging.6 They didn’t just fake a smile. They mimicked entire personalities. They could copy someone’s gestures, tone of voice, even how they laughed. Just to seem normal. Honestly, it’s the kind of performance that deserves an Oscar. Or at the very least, a therapist.

But all that pretending comes with a cost. A big one. A lot of autistic girls end up developing eating disorders. Studies by Brede in 2024 and Remnélius in 2023 basically shouted from the rooftops that there’s a strong connection between camouflaging and disordered eating in autistic girls.7 Because when you spend all your energy hiding who you are, eventually your body becomes the only thing left that you could control. It’s not about being thin or looking good for Instagram. It’s about survival. It’s about trying to keep some tiny sense of control when everything inside you feels like chaos.

Some girls don’t just copy how other people behave. They start copying entire identities. Dr. Elina Patel from University College London dug into this in a 2019 study and found something pretty intense.8 Some autistic girls experiencing gender dysphoria might not be attention-seeking at all. They might be trying on different identities because nothing feels right, and they’re desperate to find one that fits. They’re not doing it for show. They’re doing it because they don’t know who they are under all that masking.

And here’s a stat that will absolutely mess with your head. By the 1990s, about 23 percent of women diagnosed with anorexia were later found to actually meet the criteria for autism.9 So, they weren’t just dealing with an eating disorder. They were autistic the whole time, but no one saw it. Or maybe they saw it and didn’t care enough to ask the right questions.

It’s not like autistic girls just suddenly started existing in the last few decades. They were always there. Just like Pluto didn’t suddenly pop into existence when we discovered it. It was always there. We just weren’t paying attention. A

2020 study found that when doctors reviewed behavioral profiles without knowing the child’s gender, the autism diagnosis rate for girls jumped by 30 percent.10 So, the problem isn’t that there weren’t autistic girls. The problem is that everyone was so focused on the loud, obvious signs of “boy-style” autism that they totally missed the girls quietly falling apart in the background. The rise in autism diagnoses among girls doesn’t mean more girls are suddenly becoming autistic. It means we’re finally looking in the right direction. Same girls. New glasses.

Dr. Judith Gould, who helped create the Lorna Wing Centre for Autism, explained it perfectly. Girls don’t get noticed because they’re better at pretending. They blend in. They camouflage. But that doesn’t mean they’re okay. Just because someone isn’t screaming doesn’t mean they aren’t on fire.

Autism finally made it into the official diagnosis book in the 1980s, which sounds like progress, except the criteria still described every socially awkward eight-year-old boy who had ever built a LEGO death fortress and refused to talk about anything except trains or Star Wars. If you didn’t fit that mold, too bad. You basically didn’t exist. Even by 2010, studies were still saying boys were four times more likely to be diagnosed than girls. More recent research suggests the actual ratio might be closer to two to one, or even one to one if you factor in how well girls hide it.11

But the stereotype stuck. Autism meant boys who avoided eye contact, acted like tiny professors, and were obsessed with random facts. Girls? They were just labeled sensitive. Or quiet. Or “just being girls,” whatever that’s supposed to mean.

So, girls learned to act. They masked. That means they tried really hard to seem like they were totally fine, even when things were falling apart inside. One survey from 2019 found that over 90 percent of autistic girls said they masked their behavior regularly.12 Compare that to about 60 percent of boys. These girls didn’t just fake smiles. They studied people like they were prepping for the final exam of social survival. They copied body language, speech patterns, reactions. They were basically undercover spies, blending in by sheer willpower.

And it kind of worked, for a while. Until puberty hit. Then things exploded. Suddenly everything got harder. Anxiety, depression, eating disorders, panic attacks. And the terrifying realization that nobody actually knew the real person hiding under all that pretending. Including the girl herself. That’s not just dramatic. That’s what happens when you spend years performing instead of living.

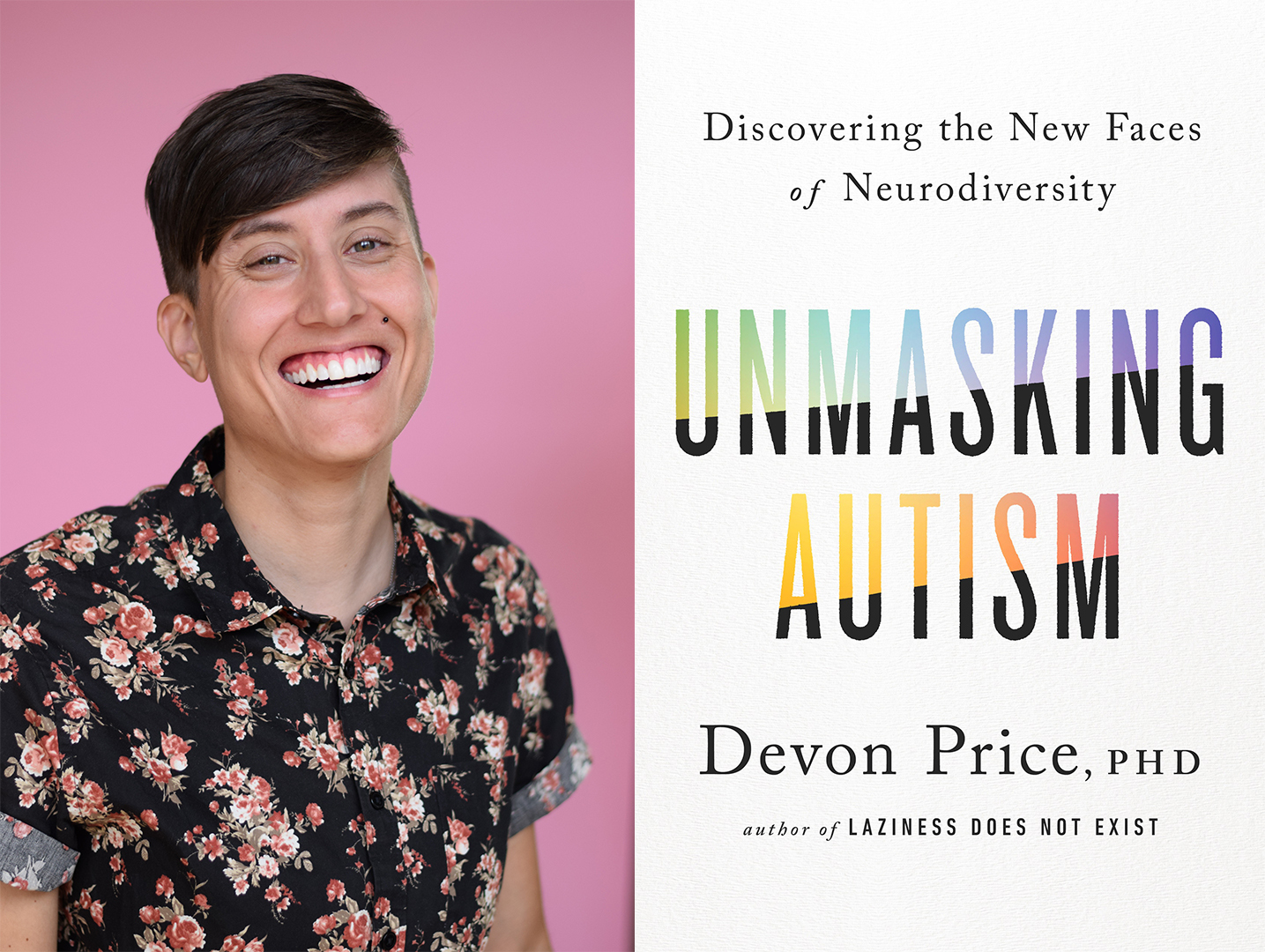

Dr. Devon Price, a social psychologist who wrote Unmasking Autism, described masking as being in drag every waking moment of your life, only the stakes are emotional survival. You’re not performing for fun. You’re doing it so people don’t judge you, exclude you, or treat you like you’re broken. And here’s a messed-up stat for you. Nearly 78 percent of autistic women were misdiagnosed with something else before they finally got an autism diagnosis.13 The labels they usually got first? Borderline personality disorder. Generalized anxiety. Bipolar disorder. Anything but autism.

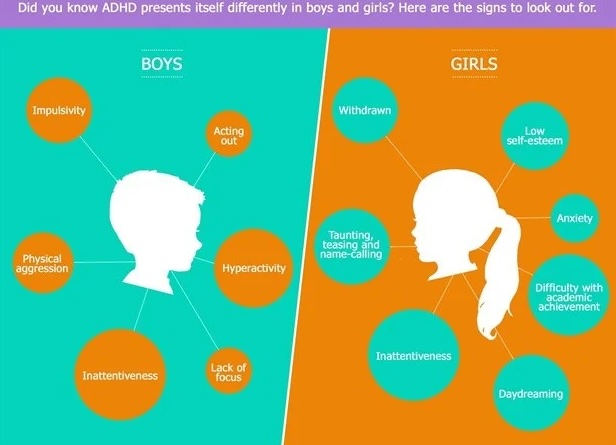

While autism was slowly, painfully crawling its way into mainstream awareness in the 80s and 90s, ADHD was off doing its own frustrating thing. Autism was seen as a social disconnect. ADHD, on the other hand, got treated like a discipline problem. The kids diagnosed early were usually boys, usually in public schools, and usually described as hyper, defiant, and basically a teacher’s worst nightmare. And by “a handful,” people usually meant “probably going to end up in juvie.” The media didn’t help either. ADHD became the label for “bad boys” who couldn’t sit still or follow rules.

Girls with ADHD were mostly ignored. They weren’t lighting classrooms on fire or climbing the walls. They were forgetting their homework. Zoning out. Daydreaming. And falling apart quietly. So instead of being diagnosed, they just got called spacey. Or lazy. Or dramatic. But at least they didn’t get criminalized like the boys, right? Well, sort of. They didn’t get punished, but they also didn’t get any support. Their symptoms got missed for years, sometimes until they were adults and suddenly couldn’t juggle life anymore.

ADHD and autism are both types of neurodivergence. They’re not the same thing, but they can overlap. You can have one without the other, but a lot of people have both. And when both show up in girls, it’s like a perfect recipe for being misunderstood by literally everyone. Teachers, parents, siblings, doctors, even therapists. Nobody sees it. Or if they do, they mislabel it. Because once again, the system was built around what these things look like in boys.

Dr. Sarah Hendrickx, who literally trains professionals on autism and wrote a book about women and girls on the spectrum, put it simply. Our whole diagnostic system was built by people who had absolutely no clue what it’s like to be a female with autism. And she’s not wrong. Dr. Tony Attwood, another big name in autism research and author of The Complete Guide to Asperger’s Syndrome, agrees. He says girls are like chameleons. They figure out what to say and how to act just to fit in. But pretending all the time is exhausting. And it takes a huge toll on their mental health.

So, are there boy disorders and girl disorders? Is autism just something boys get? Is anxiety something girls are supposed to have? Is ADHD just the brand name for hyperactive boys? Or is it possible we’ve built an entire medical system based on ancient gender roles and a whole lot of bias?

Biology definitely matters, but let’s not pretend social expectations don’t. Countless studies across all branches of medicine, from cardiology to oncology to neurology, show that men and women, people of different races, and people at different life stages often experience illnesses in very different ways.14 Symptoms can present differently, treatment responses can vary, and risk factors aren’t always the same. So yes, real biological and demographic differences exist. But instead of designing systems that account for that complexity, much of Western medicine simplified everything around one default patient: the white, middle-aged, middle-class man.

Studies show that parents are more likely to report aggressive behavior when it’s a boy and passive behavior when it’s a girl, even if the behavior is actually the same. Doctors treat those reports differently too, depending on whether the kid is a boy or a girl. So, what we call “male” or “female” disorders has more to do with how people are perceived than with how their brains or bodies actually work.

And this isn’t just about gender. It’s about a system that was designed for one very specific kind of person. As of 2015, more than 75 percent of participants in clinical mental health research were white and male.15 That means women, girls, people of color, and anyone with a lower income were barely represented. Autism research followed the exact same pattern. And if you were a girl of color? Good luck. Your chances of being misdiagnosed were even worse. For example, Black autistic girls are five times more likely to be misdiagnosed with conduct disorder before anyone even thinks to check for autism.

And just when things were starting to get better, the current administration began quietly pulling back progress. By 2024, over 60 federal agencies had removed references to diversity, equity, and inclusion. Trainings were canceled. Language that acknowledged gender and culture in healthcare just started disappearing. And this isn’t just some political fight. This is erasure. It tells millions of people that their experiences, their symptoms, and their actual lives don’t matter anymore.

So, what do we do about it? We don’t sit down. We don’t shut up. We push back. We support research that actually includes girls and women and people of color and everyone else who’s been left out of the so-called definition of normal. We teach the next generation of doctors and therapists that neurodivergence doesn’t always look like a loud little boy talking about dinosaurs. We keep fighting for better tools, better training, and better questions. Because science is only useful if it works for everyone. And that only happens if we stop pretending some people don’t exist just because they don’t fit the old mold.

Things are finally starting to shift. The idea that autism is just a boy thing is slowly dying off. More girls and women are getting diagnosed. Not because autism suddenly became more common in females, but because someone finally bothered to pay attention. Some of them are even famous. Like Susan Boyle, the singer who blew up on TV and later said she’d spent her life hiding how different she felt. Or Dr. Temple Grandin, who literally redesigned how we treat animals and helped the world understand visual thinking in a whole new way, and has a prestigious school named after her in Longmont, Colorado. Or Hannah Gadsby, the comedian who turned her pain into a Netflix special and then another one, teaching people about trauma, gender, and neurodivergence through comedy. These women didn’t just show up one day. They were always here. We just didn’t know their names.

But we’re not done yet. Diagnostic tools are still old and biased. The system is still broken. And if you’re a girl who’s also Black or Latina or from a low-income family, getting someone to actually take your symptoms seriously is still way harder than it should be. According to the CDC, white kids are one and a half times more likely than Black kids to be evaluated for autism before they turn six. That’s not a coincidence.

Even so, there’s hope. Social media and online communities are giving people a voice who were never given one before. Autistic women and nonbinary folks are telling their stories, educating each other, and rebuilding the whole conversation. Sometimes with jokes. Sometimes with facts. Sometimes with absolute fire.

If you’re a girl on the spectrum today, or if you’ve just realized that maybe zoning out in class wasn’t laziness after all, you’re not invisible anymore. At least not totally. You’ve got a better chance of being seen and understood before it’s too late. That’s progress. It only took a hundred years. Why would we waste this?

Footnotes

- Showalter, E. (1985). The Female Malady: Women, Madness and English Culture, 1830–1980. Virago Press. ↩

- Hamberg, K., et al. (2002). Gender bias in physicians’ management of neck pain. Journal of Women’s Health, 11(7), 653–666. ↩

- Kanner, L. (1943). Autistic disturbances of affective contact. Nervous Child, 2(3), 217–250. ↩

- Wing, L. (1981). Sex ratios in early childhood autism. Psychiatry Research, 5(2), 129–137. ↩

- Bargiela, S., et al. (2016). Late-diagnosed women with autism spectrum conditions. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(10), 3281–3294. ↩

- McQuaid, G. A., et al. (2022). The impact of social camouflage on mental health. Autism, 26(7), 1593–1606. ↩

- Brede, J., et al. (2020). Diagnosing Autism Spectrum Disorder in Girls. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 25(4), 889–902. ↩

- Patel, E. (2019). Gender dysphoria in autistic adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 60(10), 1026–1034. ↩

- Zucker, N. L., et al. (2007). Anorexia nervosa and autism spectrum disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 40(6), 475–477. ↩

- Loomes, R., et al. (2017). What is the male-to-female ratio in ASD? Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 56(6), 466–474. ↩

- Lai, M.-C., et al. (2014). Autism. The Lancet, 383(9920), 896–910. ↩

- Cage, E., et al. (2018). Experiences of autism diagnosis. Autism, 22(7), 827–834. ↩

- Rynkiewicz, A., & Łucka, I. (2018). ASD in girls. Psychiatria Polska, 52(2), 215–226 ↩

- Kim, A. M., Tingen, C. M., & Woodruff, T. K. (2010). Sex bias in trials and treatment must end. Nature, 465(7299), 688–69. ↩

- Chen, M. S., & Lara, P. N. (2005). Cancer health disparities and the role of the health care provider. Journal of the National Medical Association, 97(7), 956. ↩