The world has this massive problem now where tons of people—mostly young ones—are just straight-up disappearing into their rooms and not coming back out. No, they’re not in Narnia, and no, they’re not just “taking some time.” They’re stuck. And I don’t mean stuck in traffic or stuck on a math problem. I mean emotionally, mentally, spiritually jammed. Frozen in place. Like the Wi-Fi router of their soul got unplugged and no one’s even trying to fix it.1

It’s not just a Japan thing anymore, though that’s where the term hikikomori came from. Now it’s in South Korea, where teens vanish into online games like it’s their job. The government had to create tech detox camps2, which I imagine are like summer camps, but instead of s’mores, you get supervised crying and no phones. China’s got people in full-on life pause mode—they even gave them a name: NEETs, meaning Not in Education, Employment, or Training3.

Turns out, the internet is also a gateway to total emotional collapse. We’re not talking “too much screen time” like your aunt complains about. This is full-blown, mind-altering, dopamine-chasing, life-numbing internet addiction4. Globally, about 14% of people now meet the criteria for internet addiction, with rates reaching up to 20% among teenagers in some countries5. As Dr. Jean Twenge, psychologist and author of iGen, points out, there’s a noticeable shift after 2012 when smartphones became widespread6.

You know it’s bad when people start throwing around phrases like “rehab for TikTok.” And it’s not just teens. It’s students, adults, anyone with anxiety, depression, ADHD, or just a basic case of “the world is too much, and I didn’t sign up for this.”

Boys and girls both get hit by this mess, but it shows up a little differently. Boys vanish into gaming caves and quit life loud. Girls collapse quietly through filters and comparisons. In fact, 60% of social media users say it negatively impacts their self-esteem, and 63% say it makes them feel lonely7.

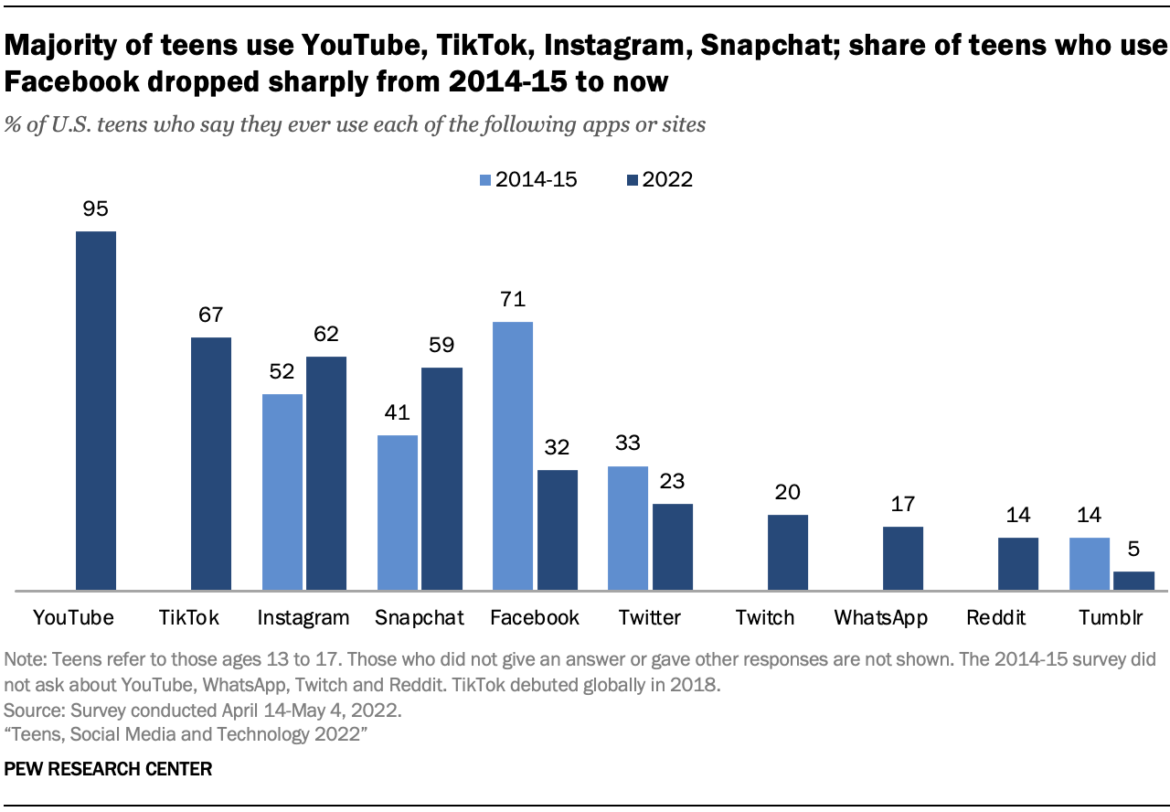

Across the board, teens are glued to their screens. Ninety-six percent say they’re online daily, and nearly half—46%—say they’re on the internet almost constantly8. According to Dr. Anna Lembke, we’ve created a world where our own brains are constantly bombarded with dopamine hits—and we’re shocked when people get addicted9.

Globally, about 70% of men and 65% of women are online, with women using a wider variety of apps and men dominating spaces like gaming and online gambling10. Internet addiction hits the same neural reward systems as gambling or drugs11.

Ricky Gervais, known for his deadpan nihilism, once remarked: “We used to chase approval from our parents. Now we chase it from strangers who would step over our corpse for a charger.”12

The people most likely to fall into this trap? Teens drowning in school stress, college kids ghosting their degrees, and people for whom real life feels like a scam. Teens spending more than three hours a day on social media are twice as likely to report symptoms of anxiety or depression13. And then came the pandemic, which basically handed everyone a golden ticket to become a digital hermit.

Dr. Michael Rich, founder of the Digital Wellness Lab, says we’ve handed kids a device that rewires their brain, then told them to use it “responsibly.”14

Therapists are overwhelmed. Teens are showing up to sessions emotionally numb. Among those logging over four hours a day on screens, 27% report anxiety, and 26% report depression15.

Amy Schumer summed it up with, “You ever realize your biggest problem is just… existing while knowing everything? Thanks, internet.” Wanda Sykes joked, “We’re out here doomscrolling like it’s cardio.” And Bill Burr nailed it: “You locked everyone inside with TikTok, no human contact, and a thousand global crises. What did you think was gonna happen?”

Teachers are losing students to screens mid-sentence. The average teen now spends 4.8 hours per day on social media alone. Schools are locking up phones in pouches and still can’t get anyone to finish a paragraph.

Governments are noticing too. South Korea, China, France, and the U.S. Surgeon General have all flagged this as a crisis. The tech industry? They’re in apology mode on podcasts, while quietly rolling out new hooks. Some call this an overreaction. Maybe teens are just adapting. Or maybe they’re silently screaming for help.

First off, we talk about it. Name it. Drag it into the daylight. This isn’t some quirky Gen Z phase—it’s an actual mental health crisis. The more we say it out loud, the less alone we all feel inside it. Next, we bring back boredom. Actual boredom. Not a crisis. Not a failure. Just silence. Let your brain get bored enough to be creative again. Stare at a wall. Blink slowly. Watch clouds. That’s where all the real magic starts. Then we touch some humans. Like, physically be around people. Go for a walk. Make eye contact. Play cards or do nothing together in real life. It’s weird at first—like taking your social skills out of the freezer—but your nervous system will thank you.

Set boundaries with your tech. Not fake rules like “I’ll only use TikTok for three hours instead of six,” but real ones. No phones at dinner. Phone goes to sleep when you do. Start small and make it stick. Start creating instead of just scrolling. Write something. Build something. Make a playlist. Bake cookies and name them after your mood swings. Doesn’t matter what—it’s the act of putting something out into the world that changes your relationship with it.

And yes, the system needs fixing too. These platforms are literally engineered to keep us addicted. So no, you’re not weak. You’re just up against billion-dollar attention traps. That’s why we need better tech design, better laws, and real consequences for companies profiting off our breakdowns. But more than anything, let’s stop pretending this is easy. It’s not. This is grief. This is burnout. This is isolation and a 24/7 livestream of everything being broken. So be kind. Be messy. Be honest about the struggle. And if all you did today was survive it—without throwing your phone out the window or throwing yourself into full shut-down mode—that’s still a win.

The world might be on fire. But maybe you don’t have to be. Maybe you just have to start.

Footnotes:

- Teo, A. R. (2010). A new form of social withdrawal in Japan: Hikikomori. Psychiatric Times, 27(2), 27–30. ↩

- Kim, J. Y., & Lee, Y. H. (2022). Internet gaming addiction prevention programs in South Korea. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 25(3), 150–156. ↩

- Furlong, A. (2006). Not in education, employment or training: The rise of NEETs in Europe. Social Policy and Society, 5(4), 431–438. ↩

- Kuss, D. J., & Lopez-Fernandez, O. (2016). Internet addiction and problematic Internet use: A systematic review. Journal of Clinical Psychology Review, 45, 14–31. ↩

- World Health Organization. (2023). Global status report on digital health 2023. Geneva: WHO Press. ↩

- Twenge, J. M. (2017). iGen: Why today’s super-connected kids are growing up less rebellious, more tolerant, less happy—and completely unprepared for adulthood. New York: Atria Books. ↩

- Royal Society for Public Health. (2017). #StatusOfMind: Social media and young people’s mental health and wellbeing. London, UK. ↩

- Pew Research Center. (2022). Teens, social media and technology 2022. Washington, DC. ↩

- Lembke, A. (2021). Dopamine Nation: Finding balance in the age of indulgence. New York: Dutton. ↩

- International Telecommunication Union (ITU). (2023). Measuring digital development: Facts and figures. Geneva: ITU Publications. ↩

- Montag, C., & Walla, P. (2016). Carving the Internet addiction spectrum: Reflections on neuroimaging findings. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1366. ↩

- Gervais, R. (2018). Humanity [Comedy special]. Netflix. ↩

- Twenge, J. M., & Campbell, W. K. (2018). Associations between screen time and lower psychological well-being among children and adolescents: Evidence from a population-based study. Preventive Medicine Reports, 12, 271–283. ↩

- Rich, M. (2021). Digital wellness and responsibility in the screen age. Journal of Adolescent Health, 68(3), 375–377. ↩

- Rideout, V., & Robb, M. B. (2019). The Common Sense Census: Media use by tweens and teens 2019. San Francisco: Common Sense Media. ↩