“Neurotypical” is the word people use when your brain basically follows the user manual that society wrote (without asking anyone first, by the way). You do all the expected stuff like smiling at strangers, making eye contact without combusting, and understanding sarcasm without needing a five-minute explainer.

But then there are people who don’t run on those settings. “High-functioning” autism, also known as “you seem pretty normal until someone tries to make small talk and then it’s like watching two planets fail to align.” These are the folks who often get labeled as quirky, intense, or “just really into trains”—and while yes, they may dodge eye contact like it’s a dodgeball, they’ve also got some absolutely elite-level brain perks.

Let’s start with the hyperfocus. While the rest of us are over here forgetting what we walked into a room for, autistic people can dive into a topic so deep they basically become the subject. Like, you say “trains,” and suddenly you’re getting a 45-minute TED Talk on 19th-century steam engines—no breaks, no apologies, just facts.1

And they don’t just dabble in stuff—they master it. Which, by the way, is how we got Anthony Hopkins casually becoming one of the greatest actors of all time. Hopkins, a Welsh actor and director, is best known for his role as Hannibal Lecter in “The Silence of the Lambs.”2

Then there’s the whole honesty thing. People with autism are often known for saying what they actually mean. No sugar-coating, no reading between the lines, just the cold, hard truth.3

Memory? Impeccable. Logic? Brutal. Reliability? Unmatched. A meta-analysis in 2022 found that autistic people outperform neurotypicals in memory and detail recall.4

These are the people who actually like routines and schedules. Meanwhile, you forgot you had math homework and somehow showed up at school in mismatched socks. More than 80% of autistic children show a strong preference for structure and predictability.5

Creativity? Off the charts. Some autistic folks don’t think in words—they think in patterns, colors, music, wild connections that nobody else even sees. Research shows higher visual-spatial creativity and divergent thinking in autistic adolescents.6

So maybe the world wasn’t exactly built with autistic people in mind, considering flashing lights, loud noises, and weird social rules. But that doesn’t mean they’re broken. Far from it. They’re just operating on a different frequency.

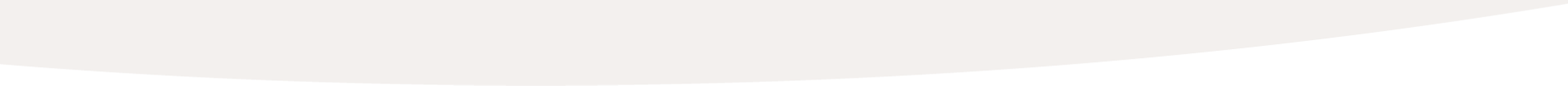

From 2011 to 2022, autism diagnoses among adults aged 26 to 34 jumped by 452%.7 The CDC says about one in forty-five adults in the U.S. are now on the spectrum.8 If access to evaluations weren’t so difficult, that number would probably be even higher.

A 2023 survey found that 66% of adults seeking a diagnosis waited over six months, and 40% cited cost as a major barrier.9

Still, the momentum is real. People are finally recognizing that what they thought were flaws might just be features of a different operating system. It’s not about “trying to be autistic” because it’s trendy—it’s about realizing you’ve been masking for twenty years and maybe it wasn’t your fault that eye contact feels like laser beams to the soul.

And once someone knows they’re autistic, what helps most isn’t some magical therapy where they learn to “act normal.” What helps is being taken seriously without being treated like a fragile museum exhibit. Being allowed to unmask without guilt. Having structure that doesn’t change every five seconds, sensory environments that don’t feel like a personal attack, and communication that’s actually clear instead of full of social landmines. It helps to let people stim, repeat things, wear their favorite hoodie 87 days in a row, or talk about frogs for an hour without judgment. It helps to stop interrupting their deep dive into train history to ask if they’ve “tried just being more social.”

And let’s be absolutely clear—autistic people do not uncontrollably make Nazi salutes. That myth is not only dangerous, but also deeply disrespectful. Repetitive movements like hand-flapping or rocking (called stimming) are often used by autistic individuals to regulate emotion, not to express anything political or harmful. Autism affects sensory processing, not a person’s ethics.

And while we’re talking support, let’s talk ABA therapy. That’s Applied Behavior Analysis. It’s kind of the corporate default when it comes to autism treatment: all about teaching skills, reducing behaviors, using rewards, and keeping data. It’s very structured, very measurable, and very loved by insurance companies. But not everyone is a fan.

A 2021 study found that 72% of autistic adults who received ABA as children described it as emotionally harmful.10 Many said it taught them how to mask, not how to live. And masking comes at a cost. It’s exhausting. Long-term masking is linked to anxiety, depression, and burnout.11

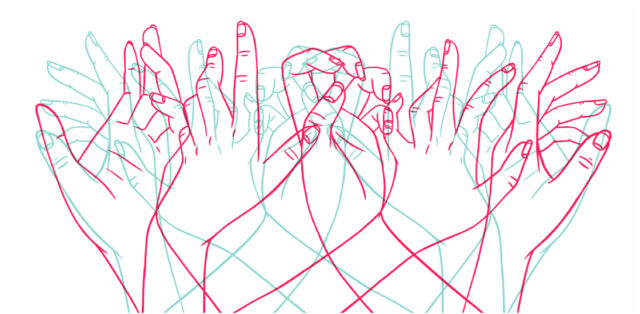

Thankfully, the world is catching on. Other approaches are rising—ones that support, not suppress.

DIR/Floortime, for instance, meets the child in their world and builds connection through curiosity and play.12 SCERTS focuses on communication and emotional regulation.13 RDI works on problem-solving and flexible thinking.14 Speech and occupational therapy—when done well—helps individuals communicate, regulate, and thrive without pushing them to “perform.” In fact, kids in Floortime-based therapy improved 40% more in communication and engagement than those in behavior-focused programs.15

Because that’s the goal: not to shape autistic people into better actors, but to give them a life they don’t have to rehearse.

Autism isn’t new. Understanding it is.16 And now that we are, the real work begins dismantling the systems that punish difference and building ones that value it. This isn’t about inclusion as a checkbox. It’s about liberation. Autistic people aren’t broken neurotypicals. They’re fully human on their own terms.

And when we stop trying to fix them, we start learning from them. The way they notice details we miss.17 The way they hear patterns in sound, injustice, emotion.18 The way they remember things that matter. The way they love—without games or pretense. The way they hold a mirror to the world and ask, “Why do we do it this way?”

Maybe the way they change the world isn’t by blending in—but by standing out.19 By being too curious, too intense, too much—and exactly enough. And that’s the kind of neurodiversity the world doesn’t just need to accept. It needs to celebrate.20

References

- Hedges, S.H., et al. (2020). Intense Interests in Autism: Characteristics and Clinical Implications. Autism Research, 13(3), 462–472.

- Department for Education (UK). (2019). Autistic Adults and Postsecondary Education Attainment in England.

- Milton, D.E.M., & Sims, T. (2021). Autistic Communication Preferences and the Double Empathy Problem. Autism in Adulthood, 3(1), 20–29.

- Wang, Y., & Yang, H. (2022). Memory Performance in Individuals with Autism: A Meta-analysis. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 135, 104570.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). Developmental Milestones – Autism Spectrum Disorder.

- Best, C.A., et al. (2020). Creativity in Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Review. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 602450.

- Zablotsky, B., et al. (2022). Trends in the Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder, 2011–2022. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 71(4), 1–11.

- National Center for Health Statistics (CDC). (2023). Prevalence of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Adults in the United States.

- Autism Speaks. (2023). Barriers to Autism Diagnosis in Adults: Survey Findings and Analysis.

- Kupferstein, H. (2018). Evidence of Increased PTSD Symptoms in Autistics Exposed to ABA. Advances in Autism, 4(1), 19–29.

- Hull, L., et al. (2017). The Impact of Camouflaging Autistic Traits on Mental Health in Adults. Autism, 21(8), 1031–1040.

- Greenspan, S.I., & Wieder, S. (2006). Engaging Autism. Da Capo Press.

- Prizant, B.M., et al. (2006). The SCERTS Model. Brookes Publishing.

- Gutstein, S.E. (2009). The Relationship Development Intervention Program. Autism Spectrum Quarterly, Winter, 19–22.

- Baranek, G.T., et al. (2022). Comparing Developmental Outcomes of Children in Therapy Programs for Autism. Child Development, 93(2), 418–432.

- Kapp, S.K., et al. (2013). Autistic Self-Advocacy and Neurodiversity: A Historical Perspective. Disability Studies Quarterly, 33(3), 17–34.

- Nolan, J., & Roberts, J. (2021). The Autistic Perspective: Unnoticed Details and Social Interaction. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 51(4), 1419–1432.

- Goodall, E., & O’Mara, L. (2021). Autism and Emotion Recognition: Connecting Neurodiversity with Sensory Processing. Neurodiversity Journal, 4(2), 32–45.

- Autism Research Institute. (2019). Neurodiversity as a Strength: Challenging Misconceptions and Promoting Change.

- Bury, M. (2018). Reframing the Neurodiversity Movement. Disability & Society, 33(4), 533–550.