We’ll talk about trauma. We’ll talk about serotonin. We’ll talk about childhood neglect, mood stabilizers, the therapeutic alliance, dopamine, the orbitofrontal cortex. We’ll talk about suicidal ideation and existential despair. But mention that a patient saw a dead relative in the hospital hallway before going into cardiac arrest? Say out loud that a six-year-old recalls—with unnerving specificity—a life they never lived? Or that someone is afraid of their house because they feel something watching them? Now you’ve crossed the line from clinician to crank.

There are certain things you’re just not supposed to say out loud in professional settings. And they all start with the same quiet question: What if there’s more to the mind than what we’ve mapped so far?

I’m a psychiatrist. I’m trained in the evidence base. I’ve prescribed the meds, followed the protocols, filled out the billing codes. But I’ve also listened to hundreds of patients describe things that don’t fit neatly into diagnostic categories—and I’m not the only one. These stories are not all psychosis. They are not all traumas. They are not all metaphors. Some of them are just…weird. And disturbingly consistent.

Science is supposed to be about asking questions. But when it comes to what happens before we’re born, what might happen after we die, or whether consciousness could ever exist outside the brain—we shut the door. Not because the data is bad. But because the implications are.

It’s time to talk about the questions psychiatry is uniquely positioned to ask—and the ones it’s been trained to avoid.

Comedian Ricky Gervais once said, “I didn’t exist for billions of years before I was born, and I’m not bothered by that. I won’t exist for billions of years after I die, and I won’t be bothered by that either.” It’s clean, symmetrical logic—the kind of atheistic clarity that calms a lot of modern thinkers. The philosopher Epicurus made a similar point about the irrelevance of death. And if consciousness is nothing more than electrical activity in a carbon-based organ, then that’s the whole story.

But what if it’s not?

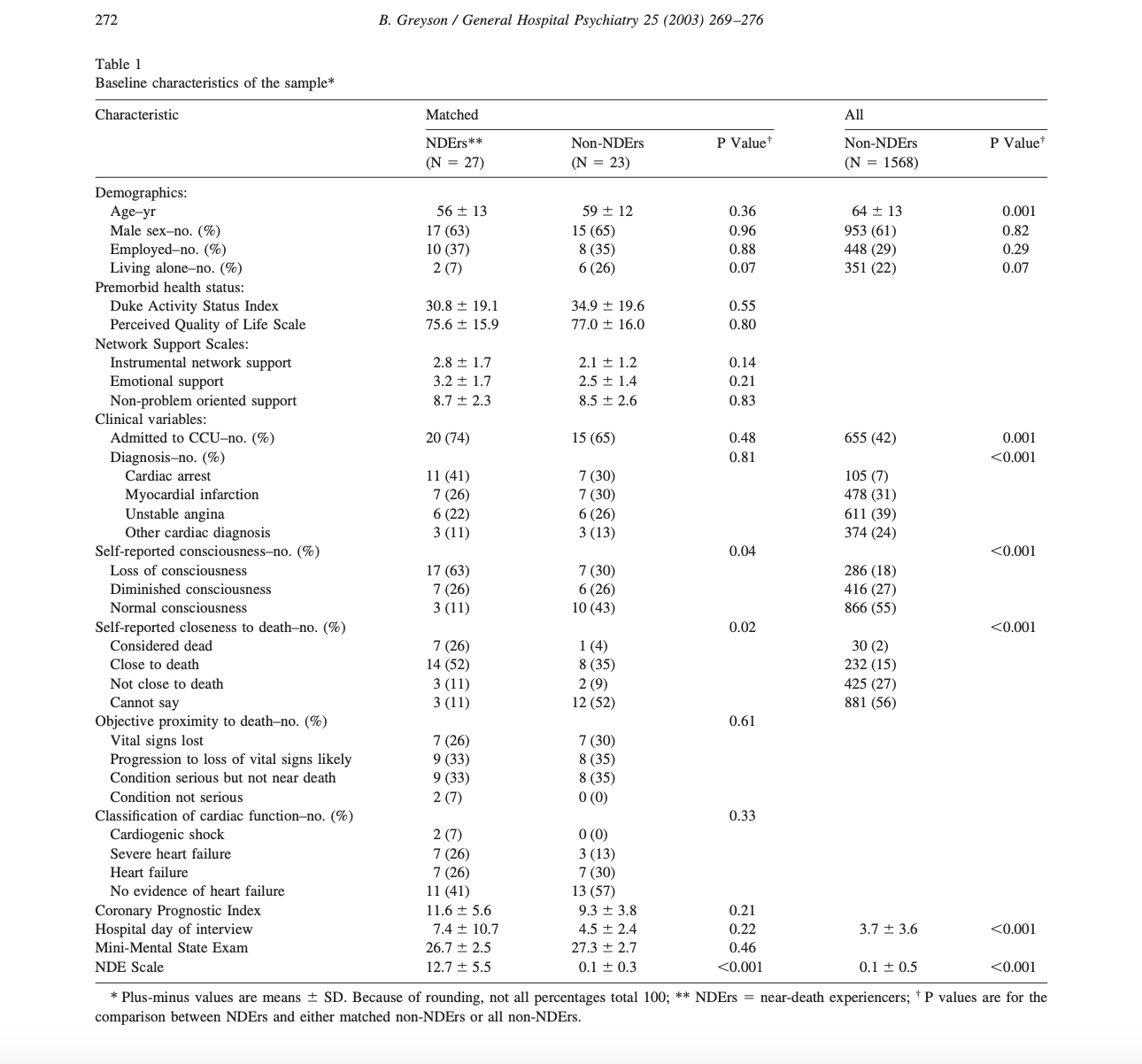

Near-death experiences (NDEs) are far more common than most of us realize. A Gallup poll estimates that about 5% of Americans have had one.1 A 2019 study across 35 countries found that 10% of participants reported an NDE—often with detailed, consistent features like tunnels, lights, reunions with deceased loved ones, and panoramic life reviews.2 These aren’t fringe hallucinations. They’re recurring human experiences, happening across age, culture, and belief system.

Children—many of them without any cultural or religious exposure to reincarnation—sometimes describe previous lives with astonishing specificity. The University of Virginia’s Division of Perceptual Studies has documented over 2,500 cases in which young children, usually between the ages of 2 and 6, speak about other lives.3 Some remember names, addresses, causes of death—details that have, in a number of cases, been independently verified. About 75% of these children describe dying in violent or unexpected ways, and many have phobias or birthmarks corresponding to those injuries.4

Then there are the more everyday anomalies: the unmistakable sensation of being watched (“scopathesia”, which has been shown to produce measurable physiological changes),5 dreams that come true, twin telepathy, or the classic moment when you think about someone and they call. Déjà vu is reported by 60–80% of people at least once.6 These are so ubiquitous we’ve trained ourselves to ignore them.

As clinicians, we hear these stories often. And yet we rarely say much, because to take them seriously risks crossing a professional line. There’s an unspoken rule in medicine: if you want to be taken seriously, stay well within the borders of what’s already been blessed by peer review.

And yet science has gone there—quietly, rigorously, and in a few brave cases, institutionally. At the University of Virginia, Dr. Bruce Greyson developed the Near-Death Experience Scale7 and wrote, “Near-death experiences raise the most fundamental questions human beings can ask: Is there life after death? Is there a God? What is the nature of reality?”8 Dr. Jim Tucker, also at UVA, has continued the work of Ian Stevenson documenting children’s past-life memories and concludes, “The simplest explanation for the strongest cases is that the memories are based on actual experiences in another life.” At NYU, Dr. Sam Parnia’s AWARE studies tracked survivors of cardiac arrest and found that many patients reported vivid recollections during periods of clinical death.9 10 “Consciousness,” Parnia writes, “may not be annihilated at the point of death. It may in fact just be a transition.” Meanwhile, researchers like Dr. Roland Griffiths (Johns Hopkins) and Dr. Robin Carhart-Harris (formerly Imperial College London) have triggered NDE-like states in controlled psychedelic studies, many involving themes of ego dissolution, cosmic unity, and transcendence. Griffiths once said, “These aren’t just drug effects. They’re life-altering mystical experiences—some of the most meaningful moments in our participants’ lives.”11 12

Outside the U.S., serious work continues—if less publicly. At the University of Edinburgh, the Koestler Parapsychology Unit investigates anomalous cognition with rigorous controls.13 The University of Northampton explores NDEs and mediumship. In Paris, the Institut Métapsychique International has examined reincarnation and psychokinesis since 1919. Research programs in Sweden, India, and even Tibetan monastic universities approach these questions not as superstition but as empirical inquiry.14 15 There are places to go—real, thoughtful, serious places—for people who want to study the big questions with their eyes open.

And here’s the paradox that rarely gets talked about: while psychiatry is often dismissed in the broader culture as mechanistic, pill-pushing, or even fraudulent, it still captivates a certain kind of mind—especially in younger patients. Some of the teens and young adults I see have told me, quietly and without irony, that they want to study psychology or go to medical school to become psychiatrists. One said, “It’s very existential,” as if the field were a doorway to something much bigger than neurotransmitters. Another told me she wanted to understand “why we are the way we are”—a sentiment I’ve heard, in different phrasing, more than once. Some of this surely comes from years spent in therapy or on medication, but not all of it. Some of it is simply the product of a thoughtful, intuitive curiosity—especially in patients who are very bright, often observant beyond their years, and not content with surface-level answers.

They are not put off by psychiatry’s complexity or its controversies. They’re drawn to it because it engages the questions that other fields seem to sidestep. What is the mind? What makes a person feel real, or unreal? Why do people suffer? Why do they remember things they shouldn’t know? What happens when our experience doesn’t match our observable biology?

For many of them, psychiatry is the only discipline that seems to welcome these questions—if not always answer them. And that, too, says something. In a world that tries to explain everything through algorithms and molecules, psychiatry, at its best, still allows room for mystery.

Of course, just as these efforts begin to build credibility, they crash headfirst into a wall of popular beliefs that actively work against their legitimacy. Take the often-repeated idea that Big Pharma invented mental illness to sell pills. It’s easy to believe, especially given the very real history of ghostwritten papers, cherry-picked data, and billion-dollar marketing campaigns. But it also flattens an entire field—psychiatry—into a caricature, and by doing so, makes any inquiry into consciousness feel like a cynical side hustle. Then there’s the related notion that psychiatry pathologizes normal life. Sadness becomes depression. Grief gets a billing code. Spiritual crisis? Sounds like bipolar disorder. To many, psychiatry is already too eager to translate meaning into symptoms and experience into prescriptions.

I remember being told by a guy in my medical school class—long before any of us had chosen specialties—that people with schizophrenia “just need to be grounded.” He said it casually, as if psychosis were a kind of bad vibe, easily cured by a long walk and a cup of tea. It would have been laughable if it weren’t so revealing. That comment didn’t just dismiss schizophrenia. It dismissed the whole endeavor of psychiatry: the idea that the mind could become unmoored from shared reality, and that this wasn’t a choice, or a flaw, but a condition that deserved study, care, and respect.

And here’s the cruel irony: even as the public is skeptical of psychiatry’s authority, it’s even more skeptical of psychiatry stepping outside its lane. When we start asking whether consciousness might exist independent of brain function—or whether reincarnation, remote viewing, or survival of personality after death have any data behind them—we’re no longer seen as scientists. We’re seen as traitors to science. Because what science has come to mean, in popular discourse, is materialism. If you can’t measure it, replicate it, or monetize it, it isn’t real.

But psychiatry has always operated in the borderlands—between biology and narrative, chemistry and meaning, neuroanatomy and mystery. To pretend otherwise is to deny what we do every day: take seriously the unmeasurable. No one diagnoses depression with a blood test. We believe in trauma, in attachment, in fear of abandonment—not because they light up a PET scan, but because they are consistent, coherent, and real. Why can’t we afford that same serious attention to experiences that suggest consciousness isn’t strictly local?

I’m not advocating for abandoning rigor or adopting magical thinking. I’m advocating for intellectual courage. For asking questions even when the answers aren’t immediately testable. For not flinching in the face of mystery. And for remembering that ridicule is not the same as rebuttal.

So no, I don’t think it’s irrational to ask what happens before we’re born or after we die. I think it’s the most rational thing we can do. And I think that as psychiatrists—professionals who have always occupied the uneasy space between science and soul—we are in a unique position to explore these questions with care, humility, and maybe even a bit of awe.

That’s what science is supposed to do.

This is the natural place where the skeptical mind, and the clinical mind, raise a hand.

If psychiatry is the one discipline willing to ask these questions—what happens before we’re born, what happens after we die, whether consciousness might survive death—are we also putting ourselves at risk of undermining the very idea of mental illness? If a person sees shadowy figures in their bedroom or hears a voice that no one else can hear, do we call it a hallucination? Or do we wonder if something else is happening?

And what if it’s both?

The short answer is we don’t always know. But that’s not as hopeless as it sounds. In psychiatry, we’re trained to look for patterns. We ask: Is the experience distressing or comforting? Does it come with disorganized thought? Is the person functioning, eating, sleeping, maintaining relationships? Are there other signs of mood or psychotic disorders—delusions, paranoia, disinhibition?

We don’t diagnose hallucinations in a vacuum. We diagnose syndromes—constellations of symptoms. When someone reports hearing a voice that guides them gently but otherwise lives a full, coherent life, we might ask about culture, trauma, grief, or even spiritual emergence. But when the voice commands them to hurt themselves or insists they are Jesus, and their thought process has unraveled entirely, and the best treatment is a tinfoil hat, we start to think in terms of disease.

In other words, context matters. Coherence matters. Insight matters. Distress matters.

But here’s where things get uncomfortable: many experiences we now view as symptoms may once have been viewed as sacred. Vision quests. Prophetic dreams. Encounters with ancestors. Some Indigenous cultures treat these as part of a person’s unique role in the community, not as evidence of dysfunction. The problem is, we don’t live in those cultures. We live in a biomedical, materialist framework that’s unequipped to parse the liminal.

And so, we pathologize what we can’t explain, or we spiritualize what we can’t classify. But both of those extremes can fail the patient.

We need a middle path.

Because mental illness is real. Schizophrenia is real. Bipolar disorder is real. These aren’t just “paranormal gifts” misinterpreted by a rigid system. They involve measurable impairments—both biological and functional—and they deserve treatment, not poetic license.

But the categories we use—hallucination, delusion, derealization—aren’t always equipped to deal with the subtleties. Not everything strange is psychotic. Not everything unseen is pathological.

The challenge for psychiatrists isn’t to decide which side is right. It’s to hold space for both truths without collapsing into either denial or gullibility. To treat suffering, while not dismissing mystery. To ask, always, “Is this person well?”—and also, “Is this person trying to tell us something that doesn’t yet have a name?”

No, psychiatry shouldn’t abandon diagnostic clarity in favor of ghost hunting. But if we’re the only discipline willing to even ask these questions, we shouldn’t shrink from that responsibility. We don’t have to choose between the DSM and the divine. We can build a better bridge.

And maybe, just maybe, that’s what this field was meant for.

References

- Gallup, G. H. (1982). Adventures in Immortality: A Look Beyond the Threshold of Death. McGraw-Hill. ↩

- Facco, E., & Agrillo, C. (2012). Near-death experiences between science and prejudice. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 6, 209. ↩

- Tucker, J. (2013). Return to Life: Extraordinary Cases of Children Who Remember Past Lives. St. Martin’s Press. ↩

- Stevenson, I. (2001). Children Who Remember Previous Lives: A Question of Reincarnation (Rev. ed.). McFarland & Company. ↩

- Sheldrake, R. (2003). The Sense of Being Stared At: And Other Aspects of the Extended Mind. Crown Publishing. ↩

- Brown, A. S. (2004). The déjà vu experience. Psychology Press. ↩

- Greyson, B. (2003). Incidence and correlates of near-death experiences in a cardiac care unit. General Hospital Psychiatry, 25(4), 269–276. ↩

- Greyson, B. (2010). Seeing dead people not known to have died: ‘Peak in Darien’ experiences. Anthropology and Humanism, 35(2), 159–171. ↩

- Parnia, S., Spearpoint, K., & Fenwick, P. (2007). Near death experiences, cognitive function and psychological outcomes of surviving cardiac arrest. Resuscitation, 74(2), 215–221. ↩

- Parnia, S., et al. (2014). AWARE—AWAreness during REsuscitation—A prospective study. Resuscitation, 85(12), 1799–1805. ↩

- Griffiths, R. R., Richards, W. A., McCann, U., & Jesse, R. (2006). Psilocybin can occasion mystical-type experiences having substantial and sustained personal meaning and spiritual significance. Psychopharmacology, 187(3), 268–283. ↩

- Carhart-Harris, R. L., & Friston, K. J. (2019). REBUS and the Anarchic Brain: Toward a unified model of the brain action of psychedelics. Pharmacological Reviews, 71(3), 316–344. ↩

- Watt, C., & Wiseman, R. (2010). Exploring alleged hauntings using infrasound. In Holt, N., Simmonds-Moore, C., & Luke, D. (Eds.) Investigating the Anomalous: Research Methods for Studying the Unexplained. Routledge. ↩

- Cardeña, E. (2018). The experimental evidence for parapsychological phenomena: A review. American Psychologist, 73(5), 663–677. ↩

- Kripal, J. J. (2010). Authors of the Impossible: The Paranormal and the Sacred. University of Chicago Press. ↩