Imagine this: you’re finally in bed, the lights are out, your sheets are soft, your body is exhausted—and your brain picks this exact moment to replay that awkward thing you said in 2009. Or it suddenly decides to solve climate change, decode your ex’s last message, and count every bad decision you’ve ever made. Welcome to insomnia. It doesn’t care that you’re tired. It doesn’t care that your alarm is going off in six hours. It crashes in like an unwanted guest, steals your peace, and leaves you staring at the ceiling wondering if sleep is a scam.

As Bill Burr once said, “There’s no worse feeling than that moment during an argument when you realize you’re wrong… but you keep going.” That’s insomnia in a nutshell. You know you need to shut down and rest, but your brain just keeps going. Burr isn’t a sleep expert, but his take on the human mind being a self-sabotaging mess is pretty on brand for what insomnia feels like.

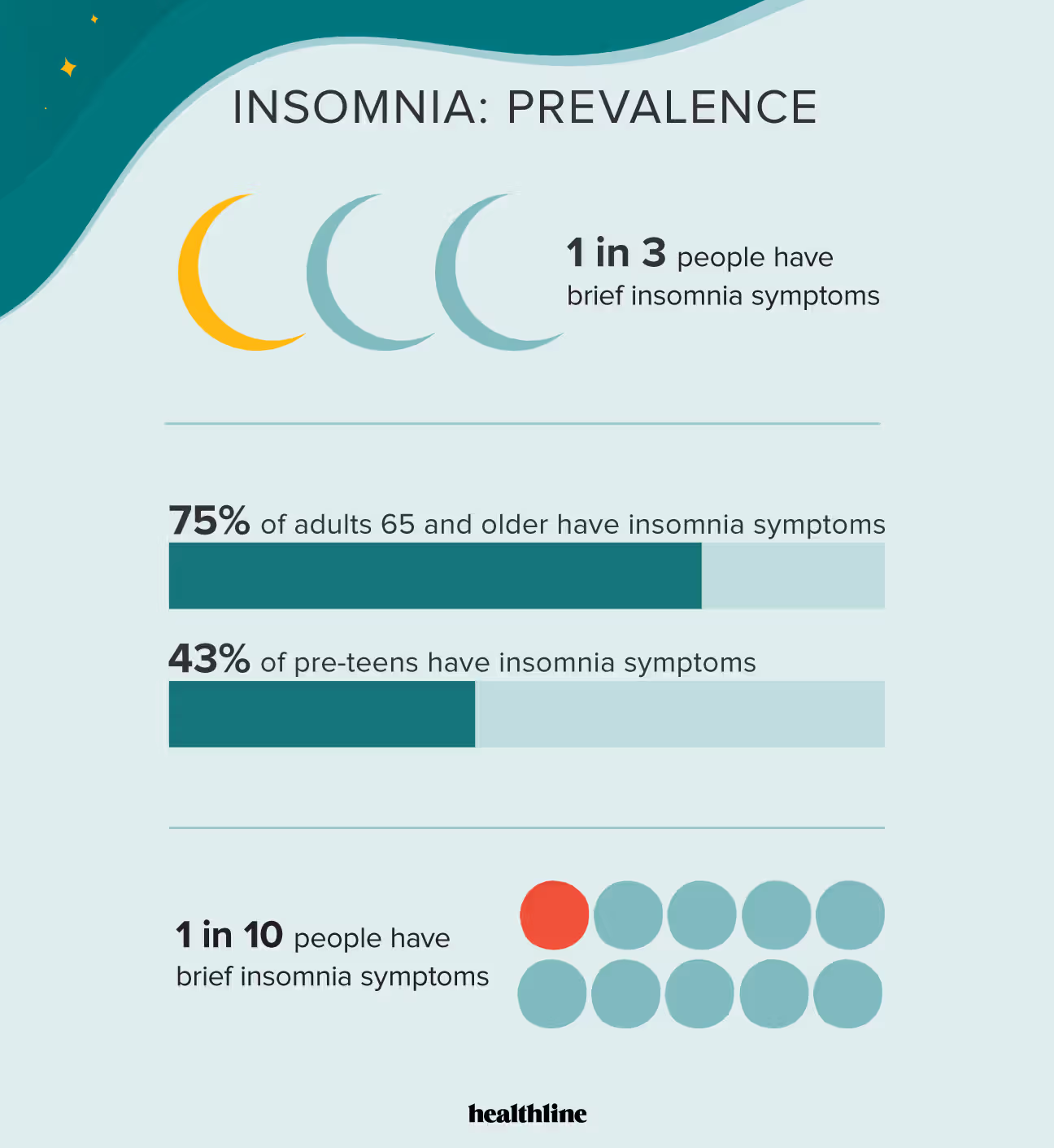

Insomnia isn’t rare. It’s not just a rough night here or there. It’s a full-blown, slow-burning crisis. Around thirty percent of adults experience short-term insomnia1. For ten percent, it becomes chronic—showing up at least three nights a week and refusing to leave2. Women are forty percent more likely to struggle with it than men3. About sixteen percent of young adults between eighteen and forty-four wrestle with it regularly. In people over sixty-five, the number is still close to twelve percent. And once it digs in, it tends to stick around. Seventy-four percent of people who report insomnia still have it three years later. Among women over fifty-five, that number jumps to ninety-five percent4.

And it’s not just happening in the U.S. Worldwide, insomnia rates range from ten to thirty percent depending on the region5. Brazil reports sleep problems in up to seventy-six percent of its population. Japan’s insomnia rates are over twenty percent. In Canada, more than half of adults struggle with sleep. Even in China, where traditional rhythms used to align more naturally with the day, insomnia is rising—especially among younger generations buckling under school stress, endless work, and glowing screens.

Mental health and insomnia go hand in hand. If you’re dealing with anxiety, depression, PTSD, ADHD, or bipolar disorder, there’s a good chance insomnia is along for the ride. About seventy-five percent of people with depression also experience sleep problems6. The same goes for anxiety. In PTSD, over seventy percent of people suffer from chronic nightmares and disturbed sleep7. People with ADHD are two to three times more likely to struggle with insomnia symptoms. Schizophrenia and bipolar disorder also feature disrupted sleep, frequent waking, and a battle between rest and overstimulation8. Insomnia doesn’t just show up because of mental illness—it makes it worse. The less you sleep, the more emotionally reactive you become. Your mood crashes, your memory fades, your focus disappears, and your ability to cope gets buried under the fog. Insomnia doubles the risk of developing depression9. People with chronic insomnia are five times more likely to develop anxiety. One study showed that even a single night of poor sleep can reduce your brain’s ability to regulate emotions by up to sixty percent10.

Dave Chappelle once said, “The worst thing to call somebody is crazy. It’s dismissive.” That lands hard when you’re lying awake at night wondering if your insomnia is just a personal failure instead of a legitimate health issue. Because that’s what it can feel like—being dismissed for something invisible that quietly wrecks your entire system.

You don’t have to be mentally ill to be sleep-deprived. Modern life does a fantastic job of making sure nobody sleeps. There’s the midnight binge-watching, the phone notifications lighting up your room like Vegas, and caffeine masked as ambition. One study found that using screens within an hour of bedtime delayed sleep by thirty percent and lowered quality significantly11. Another showed that blue light exposure from devices suppressed melatonin by over fifty percent12.

Athletes are some of the few people who’ve fully grasped the value of sleep. LeBron James treats it like a superpower and aims for eight to ten hours a night13. He’s talked about how critical it is for physical and emotional recovery. WNBA champion Nneka Ogwumike says managing rest is just as vital as managing workouts. Serena Williams has put it bluntly: “Sleep is a weapon. I use it.” These are high-performance humans, and they guard sleep like it’s a key player on the team. Because it is.

Late-night eating doesn’t do you any favors either. People who eat within three hours of going to bed are forty percent more likely to have trouble sleeping14. Spicy foods trigger vivid dreams in almost eighteen percent of people. If you have acid reflux, you’re two to three times more likely to deal with insomnia. Midnight snacks may feel comforting, but they’re often sabotaging your sleep more than they’re soothing you.

And if your insomnia includes nightmares, that’s a whole different level. About four percent of adults deal with frequent nightmares, but in people with PTSD, that number jumps to over seventy percent7. These aren’t just unpleasant dreams—they’re full-on adrenaline-fueled horror shows that yank you out of sleep and leave you drenched and disoriented. Nearly sixty percent of people with nightmare disorder also have insomnia15. It’s a brutal combo.

Medication can help some people. Prazosin, originally a blood pressure drug, has been shown to reduce nightmares by blocking adrenaline’s effects in the brain. In one clinical trial, users reported nearly two fewer nightmares a week and a forty-one percent improvement in sleep quality16. Another option is imagery rehearsal therapy, or IRT—a method where you literally rewrite the ending of your nightmare while awake, then mentally rehearse the new version. It sounds odd, but it works. Studies show it can cut the frequency of nightmares by up to seventy percent17.

But the real heavy hitter in insomnia treatment is cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia, or CBT-I. This is structured, science-backed, behavioral reprogramming. It works by reshaping your thoughts, habits, and triggers around sleep. It’s not just advice—it’s a tool kit. CBT-I is the gold standard according to the American College of Physicians18. Most people improve significantly in six to eight sessions. Better yet, the results last long after therapy ends19.

And then there’s melatonin. It’s everywhere—pills, gummies, sleepytime teas—all promising natural rest. But melatonin isn’t a sedative; it’s a signal. It tells your brain it’s nighttime. It works best for circadian issues like jet lag or delayed sleep phase. Older adults with low melatonin production may benefit, especially from prolonged-release versions that mimic the body’s own rhythm20. But it’s not a cure-all. Random dosing and bad timing can actually backfire, and most people are self-prescribing without guidance21. It helps some—but it’s not magic.

Monty Python once said, “No one expects the Spanish Inquisition.” Insomnia is like that. You don’t plan for it, you don’t see it coming, and it never shows up at a good time. Instead of torture chambers, you get email pings, flashbacks, and a brain that wants to monologue about your middle school haircut at 2 a.m.

Modern culture sells us the idea that sleep is optional. That hustle is honorable. That exhaustion is proof of effort. But every hour you stay awake when your body wants to rest is an hour someone else profits from your attention, your labor, your clicks. This isn’t a flaw in the system—it is the system.

But you can opt out. You can treat sleep like what it is: non-negotiable. As WNBA legend Sue Bird put it, “Rest isn’t a reward—it’s a requirement.” Sleep isn’t a sign of weakness. It’s resilience. It’s protection. It’s a refusal to let burnout be the baseline.

So, if you’re struggling, do something about it. Talk to your doctor. Ask about CBT-I. Look into prazosin or IRT if nightmares are hijacking your nights. Ditch the scrolling, the caffeine after dinner, the guilt about going to bed early. This isn’t indulgence—it’s maintenance.

You’re not broken. You’re just tired. And no one is handing out gold stars for who suffers the most. What you owe yourself isn’t more endurance. It’s rest. And it’s time to start fighting for it.

Footnotes:

- Ohayon, M.M. (2002). Epidemiology of insomnia: what we know and what we still need to learn. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 6(2), 97–111.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA.

- Zhang, B., & Wing, Y.K. (2006). Sex differences in insomnia: a meta-analysis. Sleep, 29(1), 85–93.

- Zhang, J., et al. (2012). Insomnia disorder in older adults: persistence and predictors. Sleep Medicine, 13(1), 60–65.

- Léger, D., et al. (2008). Insomnia and its treatment in France: epidemiological data and economic impact. Sleep Medicine, 9(1), 18–24.

- Riemann, D., et al. (2001). The comorbidity of insomnia: a review of the literature. American Journal of Psychiatry, 158(8), 1155–1163.

- Germain, A. (2013). Sleep disturbances as the hallmark of PTSD: where are we now? American Journal of Psychiatry, 170(4), 372–382.

- Kaplan, K.A., & Harvey, A.G. (2009). Insomnia and Hypersomnia in Bipolar Disorder. Current Psychiatry Reports, 11(6), 539–546.

- Baglioni, C., et al. (2011). Insomnia as a predictor of depression: a meta-analytic evaluation. Journal of Affective Disorders, 135(1–3), 10–19.

- Yoo, S.S., et al. (2007). The human emotional brain without sleep—a prefrontal amygdala disconnect. Current Biology, 17(20), R877–R878.

- Exelmans, L., & Van den Bulck, J. (2016). Bedtime mobile phone use and sleep in adults. Social Science & Medicine, 148, 93–101.

- Chang, A.M., et al. (2015). Evening use of light-emitting eReaders negatively affects sleep. PNAS, 112(4), 1232–1237.

- Martin, K. (2017). LeBron James reveals the key to his dominance: sleep. CBS Sports.

- Crispim, C.A., et al. (2011). Relationship between food intake and sleep pattern in healthy individuals. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 7(6), 659–664.

- Nadorff, M.R., et al. (2014). Insomnia symptoms, nightmares, and suicidal ideation. Sleep, 37(1), 183–190.

- Raskind, M.A., et al. (2007). A trial of prazosin for PTSD with nightmares in soldiers. Biological Psychiatry, 61(8), 928–934.

- Krakow, B., et al. (2001). Imagery rehearsal therapy for nightmares in PTSD. JAMA, 286(5), 537–545.

- Qaseem, A., et al. (2016). Management of chronic insomnia disorder in adults. Annals of Internal Medicine, 165(2), 125–133.

- Trauer, J.M., et al. (2015). Cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic insomnia: meta-analysis. Annals of Internal Medicine, 163(3), 191–204.

- Wade, A., Zisapel, N., & Lemoine, P. (2008). Prolonged-release melatonin for the treatment of insomnia. Aging Health, 4(1), 11–21.

- Ferguson, S., Rajaratnam, S., & Dawson, D. (2010). Melatonin agonists and insomnia. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics, 10(2), 305–318.