Some girl on social media says she’s “traumatized” because a barista called her “ma’am,” and your health teacher says trauma is what happens when you experience a “distressing event,” which is vague enough to include your GPA. Trauma, PTSD, being a victim, being a survivor, it’s all real, complicated, and way more than just a buzzword. Especially when you start hearing from people like Virginia Giuffre and others who were literally trafficked as teens by adults who flew around on private jets named after body parts1. Let’s unpack that.

A victim is someone something bad happened to. It’s about the thing itself, the assault, the abuse, the betrayal, the moment where someone decided your body wasn’t yours anymore. A survivor is someone who’s still standing after it. It’s not about what happened, it’s about what came next. Some people like “survivor” because it sounds strong, empowered, like they made it out. Others still say “victim” because, they may want people to remember that it wasn’t okay, that the harm was real, and that the adult man who flew them to his island didn’t do something they could just “get over.” Both terms are valid.

An injury is the thing that happens. It can be physical, like a bruise or broken bone, or psychological, like when someone destroys your trust or shatters your sense of safety. Trauma is what your nervous system does with that injury. It’s the part where your brain says, “Nope, can’t process this,” and hits the emotional panic button. It doesn’t even matter what the thing was, what matters is how your body experienced it. You could get in a car accident and walk away totally fine or cry every time you hear tires screech. One is PTSD, or Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, the other an Acute Stress Reaction. Same event, different nervous systems.

PTSD is when trauma moves in, sets up camp, and refuses to leave. You get flashbacks. You avoid stuff that reminds you of the thing. You’re constantly on edge. Your emotions either shut off like a dead iPhone or explode like a Coke bottle someone added Mentos to or shook too hard. But not everyone with trauma gets PTSD. And not everyone with PTSD got it from something society considers “dramatic.” Trauma isn’t a competition, no matter how many people want to play the “who had it worse” Olympics. About 6 percent of the U.S. population will have PTSD at some point in their lives2. Among veterans, that number jumps to nearly 30 percent in some groups3. Now consider how the many survivors react to learning that Ghislaine Maxwell may be pardoned.

If you’re dealing with this stuff, there’s actually a whole menu of things that can help. You’ve got therapy, which isn’t just sitting on a couch while someone nods and says “mmhmm.” Real trauma therapy includes things like EMDR, which stands for Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing. Basically, you move your eyes back and forth while thinking about horrible things and somehow, for some people, their brain stops freaking out about it. Scientists think it has something to do with how the brain processes memories during REM sleep, which is when your brain normally files all your emotional baggage4. For years, people thought EMDR was a joke. Like, “Sure, Samantha, wave your fingers in front of someone’s face and fix their childhood.” But then study after study started showing that it actually works, especially for trauma that regular talk therapy just bounces off. So now everyone’s on board. Therapists. Veterans. People who used to think essential oils were the answer. It’s the new star of the trauma treatment world, and for once, it’s not just hype. In fact, one meta-analysis found that 84 percent of people with single-event trauma no longer met criteria for PTSD after six sessions of EMDR5.

There’s also somatic therapy, which helps people notice where their body is holding the fear and tension like some haunted storage unit. There’s cognitive-behavioral therapy, for people who like charts and homework, and trauma-focused CBT, which is basically CBT but with more kindness and less gaslighting. There’s group therapy, which is like finding out you’re not the only weird one, and that your coping mechanisms have a name. And the science backs it: CBT has been shown to reduce symptoms in up to 60 percent of people with PTSD6, and trauma-informed group therapy can lower dropout rates by almost 25 percent7.

Some people also do great with medication. SSRIs like Zoloft (sertraline) or Prozac (fluoxetine) can help tone down the background static in your brain so you’re not constantly one bad memory away from crying in the grocery store. SSRIs, or Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors, work by making more serotonin available in your brain, which can help stabilize your mood. SNRIs, which also throw norepinephrine into the mix, might be a better fit for people who need help with energy and focus too. Sometimes they work. Sometimes they don’t. Sometimes they sort of work, but with side effects that make you wonder if it’s worth it. About 40 percent of people respond to the first antidepressant they try8. The rest either need to switch meds or try additional treatments. My patients know I prefer to try other methods before turning to an anti-depressant as I believe the “cost” in side effects is often too great.

Ketamine is the new kid on the block, even though it’s been around since the 1960s and was originally used to put people under for surgery, or if you were a 90s club kid, to fall into the K-hole and hug a stranger. But now, in controlled doses, in a therapy office with real lighting and no strobe lights, ketamine is being used to treat depression, PTSD, suicidality, some kinds of anxiety disorders, and it helps alcoholics by reducing the desire for alcohol, which helps the process of stopping. Ketamine works fast, as in, same-day fast. People who’ve been in a pit for years suddenly come up for air, and they’re not even sure why. It’s not just a mood boost; it’s like the weight on your soul gets dialed down. And the trip is short. Two hours, tops. You go in, float around in your subconscious, maybe have a mini existential crisis or feel deeply connected to the universe, then you’re back on your feet before lunch. Studies show that up to 70 percent of people with treatment-resistant depression report improvement after just one ketamine session9. Consider also that “treatment-resistance” suggests that about 30% of people don’t want to get better, which is entirely untrue.

Compare that to psilocybin, the active ingredient in magic mushrooms. Psilocybin is a whole-day event. It’s the marathon to ketamine’s sprint. You take it, and then you’re on a ride for six to eight hours, maybe longer, depending on your dose, your metabolism, and whether or not you’ve ever had a long conversation with your towel. The insights can be profound. People come out saying they felt their trauma dissolve or that they forgave someone they hadn’t even realized they were mad at. It’s not subtle. It’s not quick. And you need the rest of the day, maybe the rest of the week, to integrate what just happened. Clinical trials have shown that two psilocybin sessions combined with therapy reduced depression symptoms in 71 percent of participants10.

So, what’s the difference? Besides molecule structure and how long you’re out of commission? Ketamine works primarily on glutamate, a whole different neurotransmitter system, and acts more like a circuit breaker for depression. Psilocybin works on serotonin, but in a completely different way than SSRIs. Instead of gently increasing your mood over weeks, it floods the serotonin 2A receptors and opens up a kind of temporary mental portal that lets you see your life, your trauma, and your inner chaos from a totally new angle. Ketamine can make you feel better quickly. For many, the dissociative aspect of ketamine, in the context of a comfortable setting and helpful therapist, helps them better understand their behaviors, relationships, and hopefully who they are. Psilocybin might make you understand why you feel like garbage in the first place, but it takes longer and often hits harder.

Can plant medicines help? Yes, they can. But only if you’re ready. You can’t just pop a mushroom and expect your generational trauma to pack up and leave. You need prep. You need integration. You need someone who knows what they’re doing, not your big brother, Dave, who read about it on Reddit. These treatments don’t replace therapy, they amplify it. They don’t erase pain; they help you walk through it with a flashlight instead of a blindfold. According to a 2021 survey, about 59 percent of people who used psychedelics for healing reported significant long-term improvement in mental well-being11.

And they’re not for everyone. Some people shouldn’t take them because of family history, medication interactions, or mental health conditions such as psychosis that could actually get worse12. This isn’t candy. It’s serious work, disguised as a kaleidoscopic brain journey. It’s also fun. When is going to the doctor fun? I’ve been asked if I thought ketamine therapy can help younger teens. My initial thoughts, based upon the literature and my own clinical experience, is yes. Additionally, if a teen knows they will “trip” when they come to my office, there is some useful motivation.

So take your meds if they help. Try something new if what you’ve been doing isn’t working. Just don’t fall for the hype that there’s one perfect answer. There isn’t. Mental health isn’t a vending machine where you press a button and get healed. It’s more like a messy recipe where you have to keep tasting and adjusting and forgiving yourself when it still doesn’t feel right.

And if you’re still curious, if you want to understand why you cry when someone leaves you on read-only or why your brain turns into a bowl of mashed potatoes during finals, welcome to the world of attachment theory. This is the part where you find out that how your caregiver responded to you when you were a screaming blob of emotions at age two basically laid the blueprint for how you handle relationships forever. Did they comfort you? You probably have secure attachment, which means you’re that rare unicorn who can text someone, not hear back for a few hours, and not immediately spiral into “they hate me” territory. Did they ignore you? Now you’re avoidant and pretending feelings are for losers while secretly wondering why no one ever really gets you. Were they inconsistent, loving one day and cold the next? Here is anxious attachment, otherwise known as the reason your texts now have three follow-ups and a spiral. And if they were straight-up unsafe? That’s disorganized attachment, aka trust issues with a side of “I hate you, don’t leave me” dipped in hot-and-cold sauce. You push people away and then panic when they actually leave, and your brain is basically running the world’s most confusing relationship software.

What’s wild is that these patterns don’t come with a sign or a certificate. You don’t turn eighteen and get a notification saying, “Congrats, your attachment style is avoidant, good luck with dating!” Instead, you find out when your adult relationships start looking like a drama reboot of your childhood. You freak out when someone doesn’t reply, or you can’t handle being close to someone who actually treats you well. That’s not you being broken. That’s your nervous system trying to survive based on what it learned from people who were supposed to love you. The good news is attachment styles aren’t forever. There’s this thing called earned secure attachment, which is therapist-speak for “you can heal this”13. With support, self-awareness, and probably a lot of awkward crying into your dog, your brain can actually rewire how it connects with people. It’s not magic; it’s science, it’s real changes in the brain. And no, it doesn’t mean you’ll suddenly become perfect at relationships, it just means you’ll stop reacting like a toddler trapped in an adult body every time someone cancels plans. That’s progress.

Feeling low? Must be low serotonin. Can’t sleep? Serotonin. Break up with your situationship and now you can’t eat or feel joy? But it’s not just about serotonin. That idea, the “chemical imbalance” model, was catchy, profitable, and kind of oversimplified. It’s not wrong, it’s just way too small. Mental health is more like a complicated symphony and serotonin is one of the violin players, not the whole orchestra. That’s why antidepressants work great for some people, kind of help others, and make no difference at all for the rest. It’s also why eating protein, sleeping, and seeing sunlight sometimes fix more than you’d think, even though none of those come with a pharmacy label. In fact, lack of sunlight has been linked to increased depression risk in nearly 10 million Americans who experience seasonal affective disorder14.

Forgetting your passwords? That’s not you being flaky, unless you have Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, another topic entirely. That’s your brain under threat. Trauma, stress, anxiety, they mess with your working memory like a hacker in your head. Your brain gets so busy scanning for danger or replaying old garbage that it literally cannot store new information. Your brain is just trying to keep you alive instead of helping you pass chem. Chronic stress has been shown to shrink the hippocampus, the brain’s memory center, in more than 50 percent of long-term trauma survivors15.

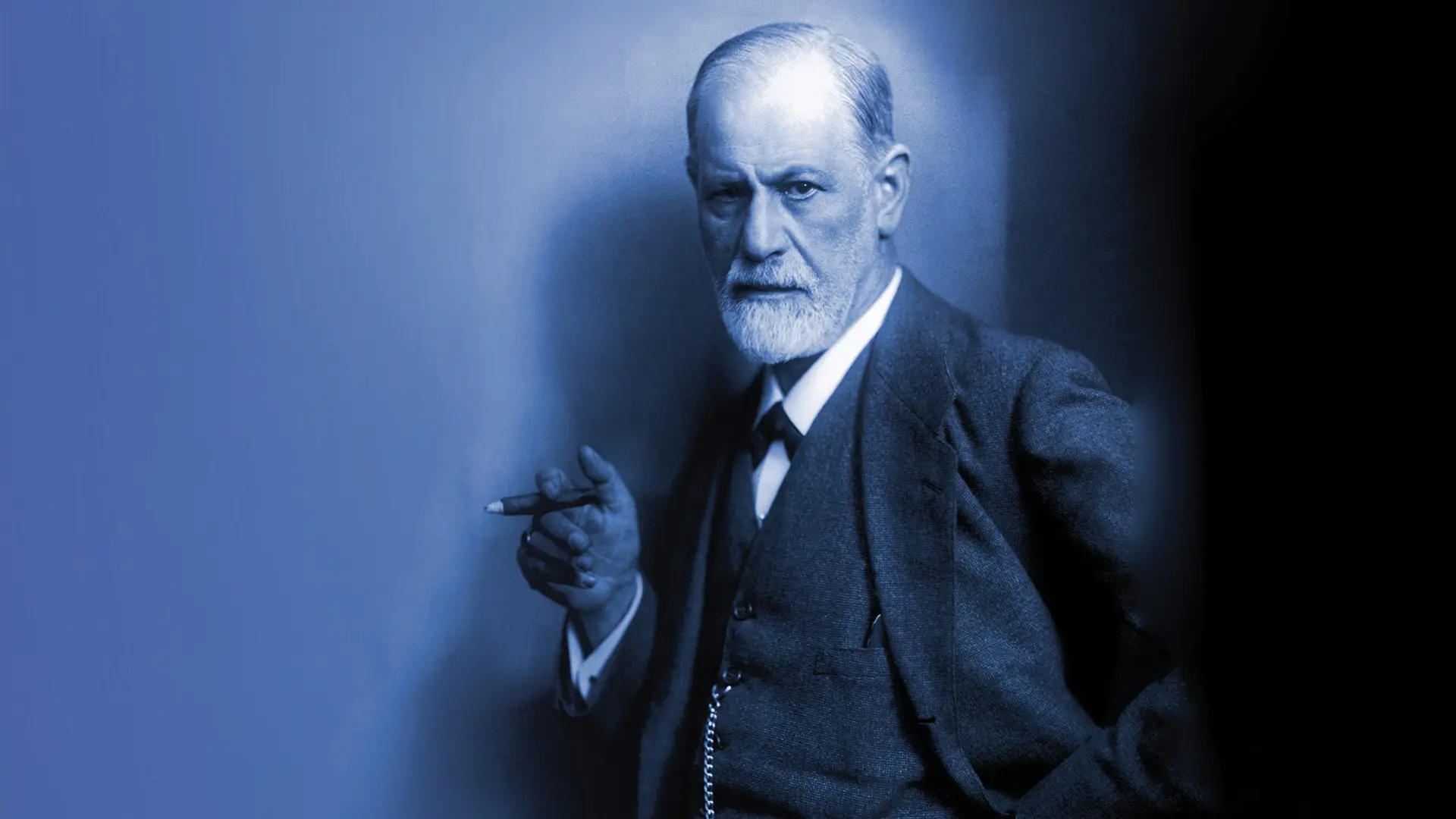

Buried underneath Freud’s nonsense about mothers was the suggestion that early relationships, especially with parents, shape everything. He got the details hilariously wrong, like blaming everything on repressed lust or toilet training, but the core idea that unprocessed emotional stuff can show up later in your adult life turned out to be sort of legit. These days we call it developmental trauma, or attachment wounds, or family systems theory.

Are we all doomed? Nah. But we do need to get better at talking about harm without getting weird or defensive. Not every hurt is a diagnosis. Not every parent is an abuser. Not every survivor wants to be called one. Not every 12-year-old crying in their room is “being dramatic.” And not every teenager who freaks out at the word “no” is a manipulative little monster. Sometimes, they’re just trying to tell you, in whatever messy, loud, uncomfortable way they know how, that something inside them doesn’t feel okay. And that should be enough for us to stop and actually listen. That’s how you remind yourself you’re not a machine. You’re a person. And that still means something, even when everything else is trying to convince you otherwise.

If any of this resonates—if you’ve been quietly wondering whether what you went through “counts,” or if you’ve tried the apps and the breathing and the “wellness” and still feel like your insides are playing static—please know you’re not alone. You don’t have to sort through it all without support. Trauma recovery isn’t a straight line, and there’s no one-size-fits-all map. But you can find your way forward—with the right flashlight, a good guide, and maybe a few naps along the way.

If you have questions, want to learn more, or are considering trauma-informed psychiatric care, I encourage you to reach out. I’m currently accepting new patients in my practice, and I’d be honored to help you navigate your own path to healing—with science, compassion, and no judgment. Contact: harrison@boulderpsychiatryassociates.com Website: www.boulderpsychiatryassociates.com

That’s not your fault. You’re not broken. You’re reacting exactly how a human is supposed to react to a world that’s built for profit, not people. The real rebellion isn’t pretending you’re okay, it’s feeling your feelings anyway. Cry in the break room. Take naps. Delete the app. Say no. Get weird. Heal loudly.

Footnotes

- Giuffre, V. (2019). The Reckoning: My Story of Surviving Jeffrey Epstein. Orion Publishing. ↩

- Kilpatrick, D.G. et al. (2013). National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60(7), 617–627. ↩

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. (2023). PTSD: National Center for PTSD. ↩

- Shapiro, F. (2001). Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing: Basic Principles, Protocols, and Procedures. Guilford Press. ↩

- Chen, Y.R. et al. (2014). “Effectiveness of EMDR in PTSD treatment: A meta-analysis.” Psychiatry Research, 215(1), 1-5. ↩

- Bradley, R. et al. (2005). “A multidimensional meta-analysis of psychotherapy for PTSD.” American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(2), 214–227. ↩

- Cloitre, M. et al. (2010). “Group therapy for PTSD: What does the evidence say?” Depression and Anxiety, 27(7), 602–610. ↩

- Gartlehner, G. et al. (2017). “Pharmacological Treatment for Adult Depression.” Comparative Effectiveness Review, No. 161. AHRQ Publication. ↩

- Feder, A. et al. (2014). “Efficacy of Intravenous Ketamine for Treatment-Resistant Depression.” Biological Psychiatry, 77(3), 190–196. ↩

- Carhart-Harris, R.L. et al. (2021). “Trial of Psilocybin versus Escitalopram for Depression.” New England Journal of Medicine, 384, 1402–1411. ↩

- Davis, A.K. et al. (2021). “Psychedelic use and mental health: Survey results.” Journal of Psychopharmacology, 35(3), 287–295. ↩

- Johnson, M.W. et al. (2008). “Risks and benefits of hallucinogen use: A review.” Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 92(1–3), 1–13. ↩

- Siegel, D.J. (2010). The Mindful Therapist: A Clinician’s Guide to Mindsight and Neural Integration. W. W. Norton. ↩

- Rosenthal, N.E. et al. (1984). “Seasonal Affective Disorder: A description of the syndrome and preliminary findings with light therapy.” Archives of General Psychiatry, 41(1), 72–80. ↩