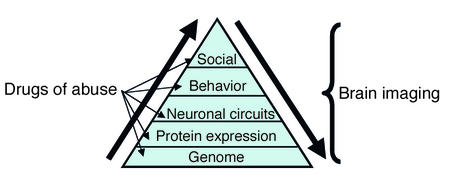

Imagine your brain is like a chill, well-balanced party. Everyone’s doing their thing—dopamine’s out there passing around snacks of motivation and pleasure—basically the brain’s hype man, making sure you care about stuff, want stuff, and get up off the couch to go after stuff. In addiction, dopamine gets completely hijacked. Substances and behaviors that trigger big dopamine surges convince your brain that this is the thing, the one thing more important than food, sleep, family, taxes, or dignity. The brain, ever efficient, starts wiring around that hit, making you crave it more and need it just to feel normal. And yep, this applies to phones too. Every ping, like, swipe, and scroll gives your dopamine a little nudge, like, “Hey! Something might be happening!” Eventually, you’re no longer checking your phone—you’re being checked by it. So yes, you can absolutely get addicted to your phone. It’s a pocket-sized dopamine slot machine.1 2

And speaking of cravings that aren’t technically drugs, let’s talk about kids and carbohydrates. Is that a thing? Oh, it’s a thing. Picture a six-year-old jonesing for Goldfish crackers like it’s their last hope for joy on this Earth. Carbs—especially simple ones like sugar and white flour—light up the brain’s reward circuits in much the same way as actual drugs.3 There’s a reason cake makes people cry happy tears on birthdays. For some kids, especially those with mood issues, sensory sensitivities, or high stress environments, carbs can become a go-to soothing mechanism. It’s quick energy, it’s dopamine, and it doesn’t judge you. Technically, it’s not addiction in the classic sense—but the compulsive behavior, emotional dependence, and withdrawal-level meltdowns say otherwise. And let’s not forget the food industry has weaponized this, engineering snacks that hit the bliss point like a sugary sniper.4 So yeah, little Timmy’s carb frenzy? It’s less about growing bones and more about chasing that soft, doughy fix.

GABA is keeping things calm like the bouncer, and glutamate is jumping around yelling facts and excitement. Now enter drugs. Not like, “whoa cool!” but more like someone spiked the punch and chaos ensues.

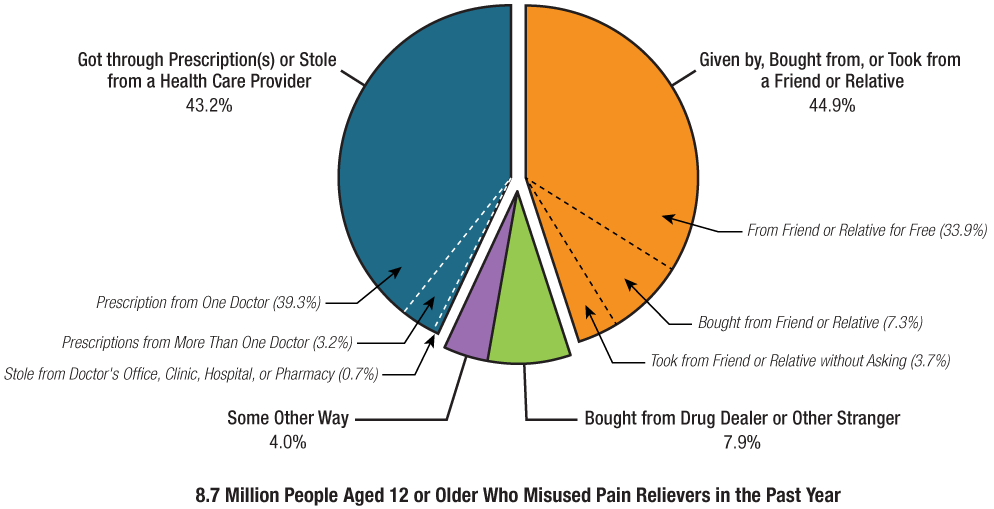

Let’s start with opioids, the ultimate comfort food for your brain. These guys hijack your natural pain relief system and crank up the “everything is amazing” knob—until you stop taking them, and suddenly you feel like you’ve been hit by a truck made of despair. You’re sweating, aching, sneezing, and wishing you’d never met a poppy plant. People say it’s not physically dangerous to withdraw from opioids, which is adorable because it feels like you’re dying.5 6

Benzodiazepines, or “benzos,” are like warm fuzzy blankets for your neurons. They calm everything down by boosting GABA, the chillest neurotransmitter. Problem is, if you take benzos too long, your brain forgets how to chill without help. Then you try to quit and suddenly your brain is like a toddler who missed naptime—screaming, anxious, possibly having seizures. Withdrawal can be so bad, it actually is dangerous. So, thanks, Valium.7

Alcohol is basically benzos’ trashy cousin who shows up at every party. At first, it’s all laughs and karaoke, but drink enough and you’re wrecking your serotonin, dopamine, GABA, and any chance of a functioning liver. Try quitting after chronic drinking, and your brain, which has been dealing with a daily flood of depressants, rebounds into a fireworks show of panic, hallucinations, and, occasionally, death. Super fun.8

Nicotine is sneaky. It doesn’t throw wild parties like the others—it just shows up, gives your dopamine a little hit, leaves, and makes you want it again in 15 minutes. It’s like an annoying guest who keeps ringing your doorbell and you keep answering even though you know it’s just going to be them again, asking to borrow a lighter.9

Psychostimulants like cocaine and meth are the maniacs of the group. They kick in the door, dump dopamine by the bucketload, and make you feel like a superhero for about 20 minutes. Then they bounce, leaving your brain a dopamine-depleted zombie swamp. You’re not physically hooked in the same way as with alcohol or opioids, but your brain will definitely be sending you passive-aggressive texts about it for weeks.10

Then there are the prescription psychostimulants—Adderall, Ritalin, Vyvanse—the preppy cousins of cocaine who show up in khakis with a to-do list. They don’t crash the party so much as they take over the DJ booth, alphabetize your thoughts, and convince you that cleaning your entire kitchen at 3 a.m. is a great idea. When used as prescribed, they can be life-changing for people with ADHD. But when misused? They’re basically academic steroids with a dopamine punch and a nasty comedown. And if you start chasing that hyper-focus high like it’s a productivity unicorn, you might end up with tolerance, mood crashes, and an unhealthy relationship with your own frontal lobe. They’re less likely to make you sell your shoes for a fix, but don’t mistake that for harmless.11

Tylenol is, frankly, the straight-A student who’s confused why it’s even being talked about here. It’s not addictive, doesn’t make you high, and just wants to quietly reduce your fever. Unless you take 30 of them and destroy your liver. Then it gets a little rowdy.

Cold medicines, especially the ones with DXM, are like the kid in high school who discovered they could get weird off cough syrup. In small doses, it just helps your cold. In high doses, it makes you feel like a sad astronaut in a glitchy video game. Some people chase that feeling, but most grow out of it once they realize it’s not exactly the ride of their lives. And your brain isn’t exactly thrilled either.

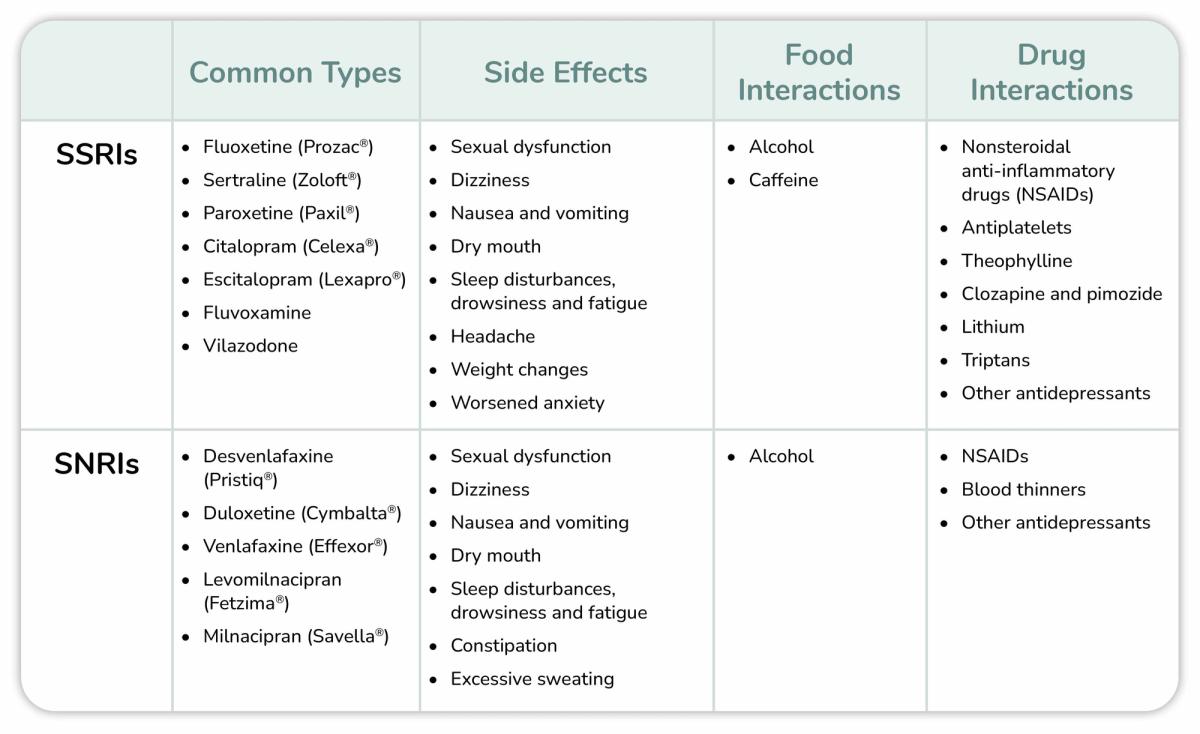

Then there are SSRIs and SNRIs—the antidepressants that somehow got lumped into addiction conversations just for showing up to help. These are the HR reps of the brain world. They don’t throw parties, they don’t get you high, but they’re trying their best to keep everyone from crying in the bathroom. You don’t crave them, you don’t rob a Walgreens for your Prozac, and frankly, it takes weeks before you even feel anything. But, if you ghost them? Especially the SNRIs? Your brain might stage a walkout: brain zaps, dizziness, crying at cereal commercials, the whole drama. That’s not addiction—that’s discontinuation syndrome.12 Still, it feels like your neurons just got dumped via text. So yeah, not addictive, but definitely not the kind of thing to quit cold turkey unless you like emotional whiplash.

This is where Robert F. Kennedy Jr. comes in swinging—and missing. He has claimed, “I know people, including members of my family, who’ve had a much worse time getting off of [antidepressants] than people have getting off of heroin.” Let’s be clear: this is absolutely incorrect. Antidepressant withdrawal, while unpleasant and sometimes lengthy, does not come close to the life-threatening physical dangers of heroin withdrawal—nor does it induce the same level of compulsive drug-seeking behavior or the overwhelming physiological dependency that characterizes opioid addiction. Comparing antidepressants to heroin is not only misleading, it’s dangerous misinformation that stigmatizes effective treatments.

This misconception is something that Dr. Carl Hart—a neuroscientist, psychologist, and professor at Columbia University—has addressed head-on. In his book “Drug Use for Grown-Ups,” Hart writes: “Most of the harm that comes from drug use stems from the policies that we have in place to punish users, not from the drugs themselves.” He emphasizes that many of the narratives around addiction have been distorted to justify fear-based policies. Hart also notes, “People who are addicted to heroin can stop using it. People recover. It’s difficult, but it’s not impossible, and it’s not a death sentence.”

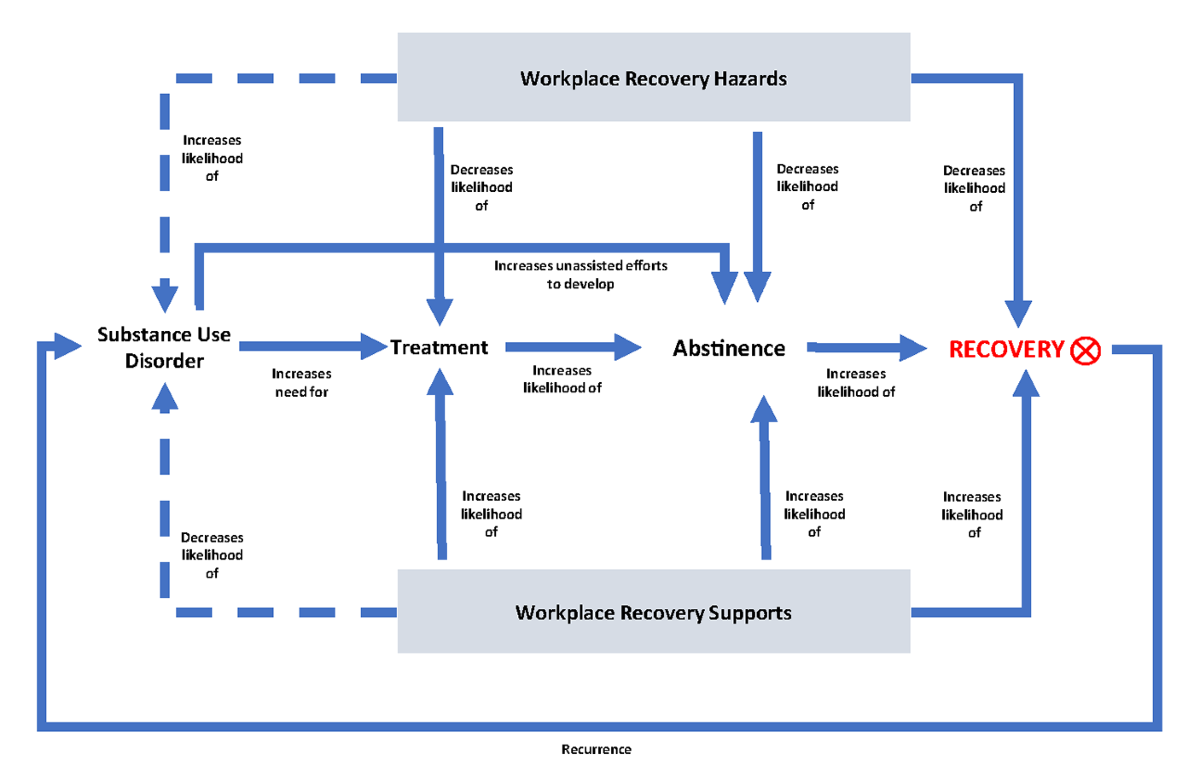

Dr. Hart’s work reminds us that context, environment, and social support are often more predictive of outcomes than the pharmacology alone. As he puts it: “When people are gainfully employed, have stable housing, and meaningful relationships, they tend to use drugs less chaotically—even if they’re using the exact same substance.”

So why take medications? Because for many people, they work. Because suffering untreated isn’t noble—it’s just miserable. And because when used thoughtfully, with real consent and oversight, meds can help you get your life back—not take it away.

We just need to stop pretending that either meds are evil OR they’re magic. They’re neither. They’re just complicated little tools in a complicated little brain party. And sometimes, when you need them, they’re exactly the guest you want.

Before we go on, it’s worth listening to a few cultural voices weighing in from their corners of society.

- Comedian Bill Burr, known for his searing honesty and blistering wit, once said in an interview, “You know what’s the problem with being depressed? You can’t get out of your own way. And people telling you to cheer up—it’s like telling someone with asthma to breathe better.” While not directly about meds, it encapsulates the cultural friction between suffering and support.

- Ricky Gervais, creator of The Office and a frequent commentator on existential angst, joked, “Just because you’re offended doesn’t mean you’re right,” when criticized for bringing up mental illness in comedy. His underlying message is consistent: honesty—even when uncomfortable—helps destigmatize mental health conversations.

- Caroline Kennedy, daughter of President John F. Kennedy and a former U.S. ambassador, has advocated for parity in mental health treatment. She stated, “Mental health is every bit as important as physical health, and it is time we started treating it that way.”

- Brian Tyler Cohen, a progressive political commentator, addressed RFK Jr.’s misinformation with his signature clarity: “There’s a difference between skepticism and recklessness. Comparing antidepressants to heroin is not just false—it’s dangerous.”

- Molly Jong-Fast, political writer and outspoken mental health advocate, tweeted, “Being on antidepressants doesn’t mean you’re broken—it means you’re brave enough to want to feel better.”

- Katie Couric, journalist and cancer awareness advocate, wrote in an op-ed: “When my husband died, I was devastated. Therapy and antidepressants helped me function again. There is no shame in seeking help.”

- And finally, John Cleese—comedic legend from Monty Python—offered this: “The mind is like a parachute. It doesn’t work if it’s not open.” He’s long critiqued stigma around mental health, using satire to show just how absurd the denial of treatment really is.

So why take medications? Because for many people, they work. Because suffering untreated isn’t noble—it’s just miserable. And because when used thoughtfully, with real consent and oversight, meds can help you get your life back—not take it away.

We just need to stop pretending that either meds are evil OR they’re magic. They’re neither. They’re just complicated little tools in a complicated little brain party. And sometimes, when you need them, they’re exactly the guest you want.

So no, not all addictions are created equal. Some make you feel amazing then leave you in the fetal position. Others don’t do much at all unless you really abuse them. But in the end, most of them are just different ways of messing with a system that—while not perfect—was doing its best before you decided to invite chaos to the party.

America is practically held together by non-drug addictions in yoga pants and push notifications. Think gambling, shopping, TikTok scrolling, porn, binge eating, workaholism, gym addiction, and that weird need to check email at red lights. These don’t come with needle marks or rehab brochures, but they hijack the same brain circuits—mainly the dopamine reward system, just without the prescription pad. The difference? You can’t smell someone’s phone addiction or see the withdrawal from not checking Instagram for 24 hours, but the crash is real: restlessness, irritability, FOMO, existential dread. When parents tell me they want their kids not to use “screens” so much, I worry the fight with Madison Avenue’s experts on “dopamine hits” is unfair to a 10-year-old.

The culture eats this stuff up because it’s profitable. Gambling makes casinos rich. Social media mines your attention like it’s digital gold. No one’s staging interventions for compulsive Amazon Prime boxes showing up at the door—we just call it Tuesday. But just like with substances, these behaviors can go from coping mechanism to full-blown parasite if you’re not paying attention. They’re legal, socially encouraged, and often come dressed up as “self-care” or “productivity,” but they burn out your dopamine just the same.

Take gambling, for example. It’s basically a psychological buffet of manipulation. The slot machine doesn’t just spit out money or not—it uses something called a “variable ratio reinforcement schedule.” That’s science talk for: you never know when the next reward is coming, which means you keep going, just in case the next pull is the one. It’s the same tactic your phone uses when you refresh your feed or check for messages: intermittent reinforcement. Combine that with flashing lights, near-misses, and loss framing, and suddenly your logical brain is out to lunch while your lizard brain is glued to the machine. Casinos are designed like adult Disneyland, but with fewer princesses and more financial ruin.

So, whether it’s heroin or hashtags, the question isn’t is it addictive? No, it asks, is this helping or hollowing you out? Because at the end of the day, addiction is less about the thing and more about what that thing is replacing. And whether it’s a pill or a pixel, if you’re using it to outrun your brain, eventually it’s going to catch up.

Which brings us to the question of treatment. How do you actually unfry your brain once it’s been pickled in dopamine and bad decisions? The good news: there are options. The bad news: none of them are magical fairy dust, and some of them require things like effort, time, and honesty.

First off, for substance addictions, you’ve got the medical big guns. Medication-assisted treatments (MAT) like methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone can help with opioid use disorder. For alcohol, there’s acamprosate and disulfiram—although that last one’s basically chemical blackmail (drink and you’ll feel like a sea-sick gremlin). Aversion therapy. Nicotine? Patches, gum, lozenges, and even medications like varenicline. These don’t “cure” addiction, but they buy your brain time to rewire without constantly screaming for its fix.

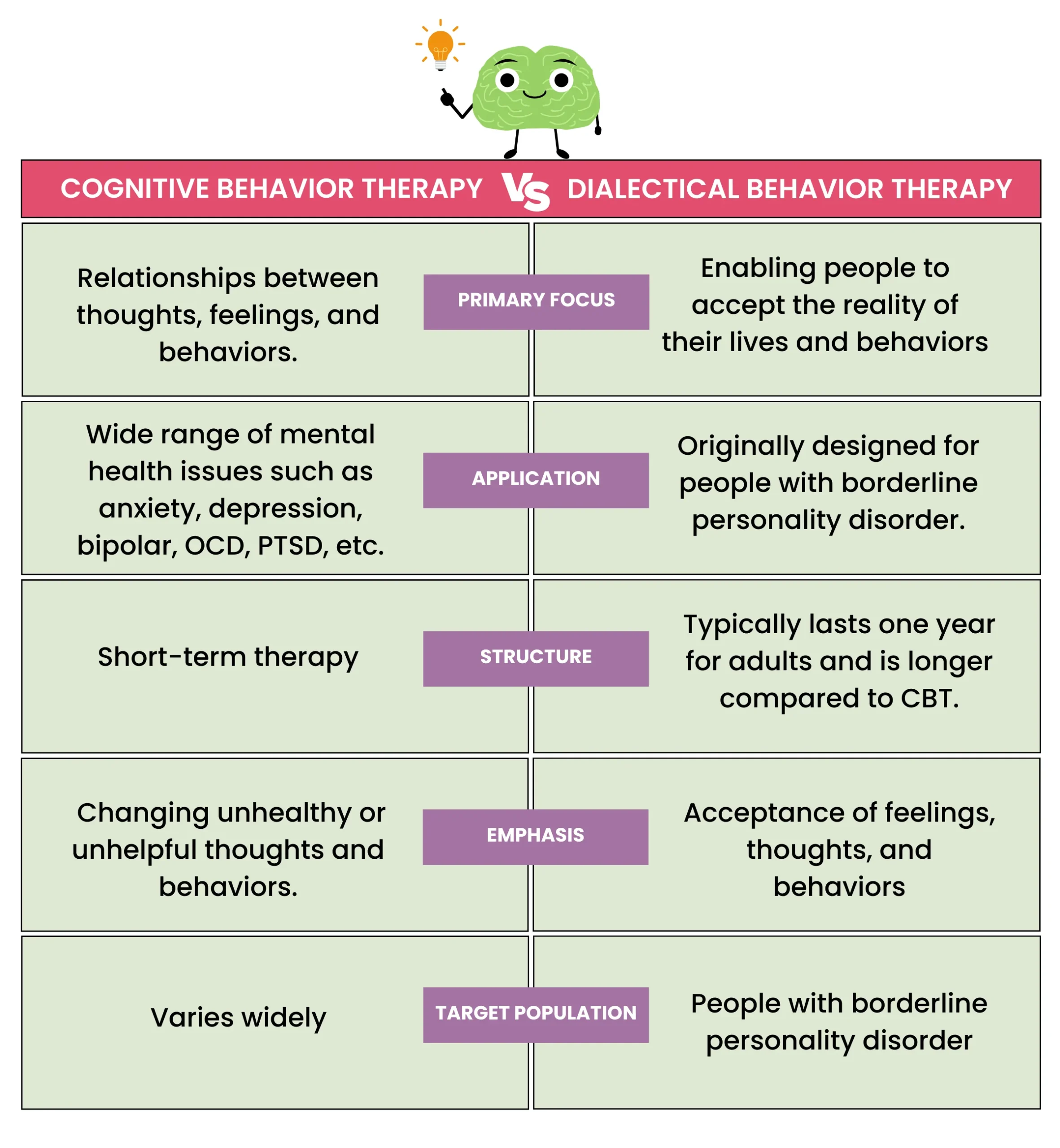

Then there’s therapy, aka the place where you dig through your mental junk drawer. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT), Motivational Interviewing (MI)—these are the gold standards, helping you unlearn the rituals, triggers, and internal monologues that say, “Sure, one more won’t hurt.” They work best when you actually show up for them.

Support groups—AA, NA, SMART Recovery, or whatever acronym fits—and suddenly you’ve got community, accountability, and maybe a few friends who don’t judge you for crying over tv commercials. Rehab and intensive outpatient programs exist too, when things have gone full-blown Netflix docuseries. Incidentally, the new Netflix series, Sirens, has a good (and funny) depiction of one of the main characters attempting to stop her use of alcohol (apparently brought on by a horrible life) but replace it with random sex.

And let’s not forget lifestyle changes, which sound boring but are lowkey revolutionary. Sleep. Nutrition. Exercise. Social connection. They won’t fix everything, but they sure do turn the volume down on cravings and chaos. Think of how these “changes” are the things that seem to be either missing or distorted for some of those who turn toward substances as a kind of replacement.

The truth is that treatment isn’t one-size-fits-all. It’s more like a grab bag of coping strategies, brain hacks, and occasional pharmaceutical sidekicks. And speaking of sidekicks, let’s talk about ketamine. Yep, that club drug-turned-breakthrough-therapy that’s now moonlighting as a mood lifter and craving killer. Turns out, in controlled doses and clinical settings, ketamine can actually help treat certain addictions—especially alcohol and opioid use—by doing some high-level Jedi stuff in your brain. It rapidly boosts glutamate and reconnects synapses like it’s rewiring your mental Wi-Fi. It won’t do the work for you (sorry, no miracle molecule here), but it can soften the blow of early recovery, reduce cravings, and give your therapy a serious head start. Think of it as a biochemical reboot—if done right. Not something to DIY in your friend’s basement.13

Narcan—aka naloxone—is the unsung hero of opioid overdoses. It’s like the defibrillator for a brain about to shut down from too much heroin or fentanyl. One spray up the nose and boom: unconscious overdose victim suddenly upright and deeply confused. It doesn’t fix addiction, it doesn’t treat cravings, but it does save lives long enough for people to get another shot at recovery. The controversy? Some people claim it “enables” drug use, which is like saying seatbelts encourage bad driving. In reality, Narcan is just a tool—one that turns “dead” into “not dead.” And frankly, that seems like a decent first step. Denying people a second chance because they’re struggling with a deadly disease? That’s not tough love. That’s just being an accessory to the obituary.14

The goal isn’t perfection—it’s progress. Getting to a place where you run your life instead of your addiction running it like a drunk raccoon with car keys.

So yes, recovery is possible. Not easy. Not linear. But possible. And it starts by admitting that maybe, just maybe, your brain party needs a new guest list.

Now, are some addictions easier to quit than others? Absolutely. Opioids and benzos, for example, have withdrawal symptoms that feel like a mash-up of the flu, an emotional breakdown, and a haunted house. Meanwhile, nicotine might just make you cranky and snacky for a bit. Quitting weed? Usually not too bad, unless you count becoming temporarily unmotivated and watching seventeen hours of Food Network. Stimulants can leave you in a puddle of depression and exhaustion but rarely try to kill you on the way out like alcohol or benzos might.

Then there’s sex addiction—yep, it’s a thing. Controversial, complex, and not as simple as being “too horny.” It’s more about compulsive behavior, using sex (or porn, or sexting, or hookups) to self-soothe, avoid pain, or chase a dopamine high that fades faster than your dignity after a 3 a.m. DM. And because sex is part of being human, you can’t exactly go cold turkey without also swearing off intimacy and relationships. So, treatment is more like learning how to drive responsibly after years of joyriding. With therapy, support groups, and a lot of unlearning. It’s less about stopping sex and more about stopping the cycle of shame, secrecy, and impulse.

So yeah, some addictions are stickier than others. Some whisper, some scream, and some show up wearing lace or holding a vape. The common denominator? They’re trying to fill a hole that can’t be filled with the thing that caused it. And quitting means learning how to fill it differently—or realizing it was never really empty in the first place.

What actually happens to people with addictions? Some recover fully and go on to become yoga instructors or peer counselors or just boringly stable people who talk about their kombucha fermentation process. Others relapse a few times (or a dozen), spend years in and out of treatment, and eventually find their way. And yes, sadly, some don’t make it. Addiction can kill. Not just your vibe—but your relationships, your job, your health, and sometimes your body.

But the good news? Long-term recovery is possible, and outcomes improve dramatically when people have access to treatment, support, housing, meaning, and enough time to screw up without being punished like a villain in a cautionary tale. Think of recovery like trying to put together IKEA furniture with no instructions, missing screws, and an audience of judgmental onlookers—you’ll probably curse, possibly cry, but if you keep at it, something functional might emerge.15

Addiction doesn’t have to be a life sentence, but it does require honesty, help, and often more resilience than most people think they have. But with the right tools, the right support, and a solid dose of stubbornness, change is not only possible—it’s happening every day. At the end of the day, addiction is less about the thing and more about what that thing is replacing. And whether it’s a pill or a pixel, if you’re using it to outrun your brain, eventually it’s going to catch up.

References

- Volkow, N.D., et al. “The addicted human brain: insights from imaging studies.” Journal of Clinical Investigation, vol. 111, no. 10, 2003, pp. 1444–1451. ↩

- Twenge, J.M., et al. “Increases in depressive symptoms, suicide-related outcomes, and suicide rates among U.S. adolescents after 2010.” Journal of Abnormal Psychology, vol. 128, no. 2, 2019, pp. 119–133. ↩

- Ludwig, D.S., et al. “High-glycemic index foods, overeating, and obesity.” JAMA, vol. 287, no. 18, 2002, pp. 2414–2423. ↩

- Institute of Medicine. Food Marketing to Children and Youth: Threat or Opportunity? National Academies Press, 2006. ↩

- SAMHSA. Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results from the 2021 NSDUH, HHS Pub. No. PEP22-07-01-005, 2022. ↩

- Wesson, D.R., & Ling, W. “The Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS).” Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, vol. 35, no. 2, 2003, pp. 253–259. ↩

- Olfson, M., et al. “Benzodiazepine use in the United States.” JAMA Psychiatry, vol. 72, no. 2, 2015, pp. 136–142. ↩

- Bayard, M., et al. “Alcohol withdrawal syndrome.” American Family Physician, vol. 69, no. 6, 2004, pp. 1443–1450. ↩

- CDC. “Smoking & Tobacco Use: Fast Facts.” 2022. ↩

- Volkow, N.D., et al. “Dopamine in drug abuse and addiction.” Molecular Psychiatry, vol. 9, no. 6, 2004, pp. 557–569. ↩

- SAMHSA. “Emergency Department Visits Involving ADHD Stimulants.” DAWN Report, 2013. ↩

- Fava, G.A., et al. “The withdrawal syndrome after antidepressant discontinuation.” Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, vol. 76, no. 12, 2015, pp. 1480–1486. ↩

- Das, R.K., et al. “Ketamine can reduce harmful drinking…” Nature Communications, vol. 10, 2019, p. 5187. ↩

- Wheeler, E., et al. “Opioid overdose prevention programs…” MMWR, vol. 64, no. 23, 2015, pp. 631–635. ↩

- Kelly, J.F., et al. “How many recovery attempts does it take…” Drug and Alcohol Dependence, vol. 170, 2016, pp. 162–169. ↩